World Bank energy investments are categorically failing to end energy poverty.

That’s the stark finding of a new report released by Sierra Club and Oil Change International which measures how multilateral development banks (MDB) fare on their efforts to end energy poverty. The report benchmarked recent MDB investments in clean energy access against the breakdown of needed investment called for in the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) “Energy for All” scenario. In that scenario, universal energy access is achieved by 2030.

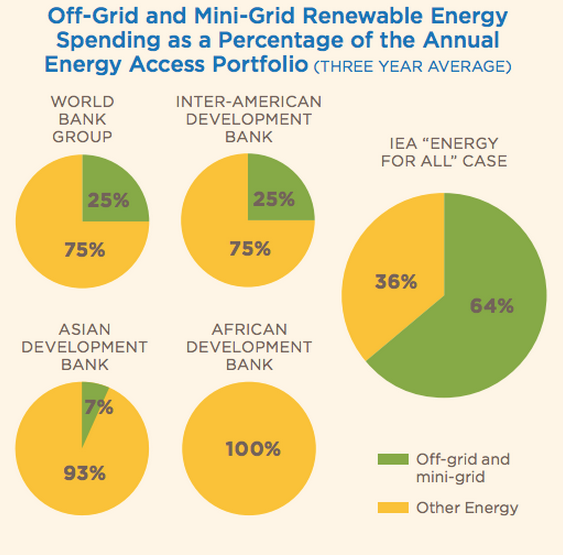

As it stands, if the “Energy for All” scenario is going to succeed, it will require 64 percent of all new investments be used to fund the fastest, cheapest, and most effective source of energy that will help energy poor populations get on to the energy ladder. That source of energy? Distributed off-grid and mini-grid clean energy systems for those living Beyond the Grid.

The problem is, the world’s foremost development institution — the World Bank — is failing miserably to live up to the IEA’s goals.

Despite the presence of wildly successful programs like Lighting Africa and Bangladesh’s IDCOL program — which has jumpstarted a booming off-grid solar market totaling 3.3 million systems installed to date — the report shows that the World Bank Group fell painfully short on its investments in clean energy access.

Key findings include that less than 10 percent of the Bank’s energy funding specifically targets the poor – a group that makes up nearly 40 percent of the world’s population, when you include people who lack access to electricity and/or modern cooking fuels. Even worse is the fact that out of that miserly 10 percent, only one quarter was spent on off-grid or mini-grid clean energy deployment — well short of the IEA’s benchmark of 64 percent.

As a result of this pitiful performance, the World Bank received an ‘F’ on its report card for energy access efforts.

But an even more important question is: Why is the World Bank failing so miserably?

As my colleague Peter Bosshard at International Rivers has pointed out, it’s structural. For instance a World Bank evaluation found in 2009 that “internal Bank incentives work against [efficiency] projects because they are often small in scale, demanding of staff time and preparation funds, and may require persistent client engagement over a period of years. This makes them less attractive to managers and agencies that use disbursement as a measure of action and large turbines as a visible symbol of achievement.”

As Peter goes on to point out, “Five years later, the Bank’s Quality Assurance Group castigated the institution’s ‘pressure to lend’, and pointed to the ‘fear that a realistic, and thus more modest, project would be dismissed as too small and inadequate in its impact.”

The World Bank’s central problem is, according to author Bruce Rich, “a culture of loan approval, institutionalized in various perverse internal incentives.”

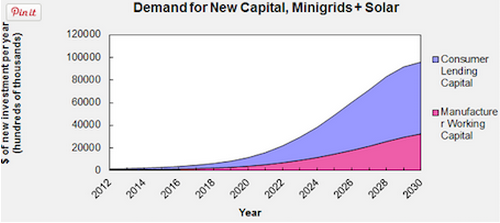

That’s why despite having a nearly $4.1 billion dollar annual energy portfolio, the World Bank has failed to pony up a meager $500 million in investment for beyond the grid clean energy markets. And our analysis confirms that investment is enough to catapult this rapidly-growing market towards a $12 billion clean energy access marketplace that can end energy poverty in our lifetime.

Aggregating investments via financial intermediaries is an already well-worn path that offers a way to overcome the problems associated with a large number of small deals. Similarly, ring-fencing resources, developing new funds, altering staff incentives, and creating mandates to lend in this market would all encourage Bank staff to invest in this space and help turn around the Bank’s failing grade.

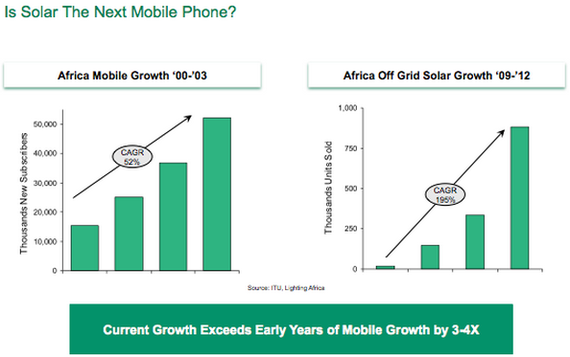

And let’s be clear: the upside to investing in these clean energy markets is tremendous. According to the Bank’s own Lighting Africa program, these markets are growing at an astounding 95 percent annual rate. Bangladesh’s IDCOL program has increased solar installations at a 60 percent rate for an entire decade. Those are growth rates roughly two times what mobile phone penetration grew at in the early 2000’s. And, to top it all off, this market solves one of the most high profile development challenges of our time.

As long as Dr. Kim remains uninterested in truly innovative approaches to ending energy poverty, the one institution that should ‘own’ this problem and provide scalable clean energy investment is sitting on the sidelines.

But World Bank or no World Bank, private investors and foundations are waking up to the opportunities in this market, with $45 million invested this year alone. That means Dr. Kim faces the very real possibility that instead of being at the vanguard of ending energy poverty, he will be missing in action.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

All signs point to the fact that Dr. Kim is serious when he talks about innovation and that he truly cares about ending poverty. If that’s truly the case, it’s time he stood up and declared a new day at the Bank; one where those taken seriously are the innovators – not defenders of the status quo.

That’s because in the 21st century, villagers won’t wait for the grid, and those that are serious about ending poverty shouldn’t promise it.

Help Dr. Kim lead the World Bank into the 21st century and demand he pledge $500 million of the Bank’s energy portfolio to clean energy access.