Above Photo: Sandra and Jerry Sloan, who run Sloan’s Wild Game Processing, live less than a mile from the Broadhurst landfill. “I figured with the money that was involved, it would go on through,” Jerry Sloan said. “I think all the people against it, fighting to keep it out of here is what stopped it.” Credit: Georgina Gustin

When news spread that Republic Services planned to dump trainloads of toxic coal ash in a local landfill, citizens, led by the local newspaper, fought—and won.

JESUP, Georgia—Peggy Riggins remembers standing against the wall of a windowless meeting room on a January day last year. Dozens of people sat in folding chairs, others crowded the aisles and more packed the hallway outside, tilting their heads to hear.

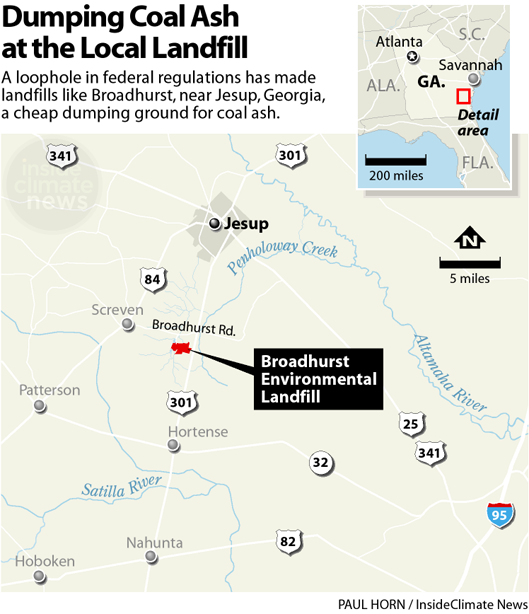

The Wayne County commissioners were unaccustomed to a big audience. But over the previous weeks, the local newspaper had uncovered plans by an out-of-town waste hauler to expand a rail line leading to the community’s landfill. County residents were getting more and more concerned with each story. This new rail spur would enable the company—later found to be Republic Services, a $9-billion firm based in Phoenix whose biggest shareholder is Microsoft’s Bill Gates—to haul 10,000 tons of toxic coal ash through the county’s swampy forestlands and into the dump every day.

Riggins, like a lot of her neighbors, had never thought much about the Broadhurst Environmental Landfill, as it is formally known, and had barely heard of coal ash. But as the news unfolded, Wayne County learned that it could become one of the biggest coal ash dumping grounds in the South, thanks to a loophole in federal regulations.

“I was shocked,” Riggins said. “I love Wayne County and I’m so proud of it. I never dreamed that someone from outside could just come in and threaten everything that’s good about it.”

A retired high school teacher who has called Wayne County home for all of her 65 years, Riggins crafted herself a new job. She met a friend at the Cafe Euro in Jesup, the county seat, and together they began strategizing. Soon after, Riggins came up with a name for the group she would lead—No Ash At All. Soon after, No Ash At All signs poked up from yards across the county.

“I felt scared for the future, scared for my grandkids,” Riggins remembers. “I was determined to do everything I could.”

Wayne County stretches across southeast Georgia’s lower coastal plain, a flat, humid sweep of pine forests and mossy swamps, overlaid with creeks and rivers that eventually spill into the Atlantic. The county’s biggest employer, the Rayonier wood-fiber plant, hulks at the eastern edge of Jesup on the Altamaha River—the “Amazon of the South.” Highway 301 cuts through the county’s midsection, past 17 boarded-up motels, once populated by northern “snowbirds” on their way to Florida for the winter. Travelers use Interstate 95 now.

From a garbage haulers’ perspective, Wayne County is a perfect dumping ground: it’s relatively poor and out of the way. From an environmental standpoint, though, it’s a particularly bad place to put toxic material in the ground: it’s covered in wetlands and in the middle of a network of waterways that connect every living thing in the county and beyond.

And now Republic proposed bringing in trainloads of toxic dust.

The U.S.’s coal-fired power plants churn out more than 100 million tons of coal ash a year, making it the country’s second largest waste product after household trash. Power companies typically dump coal ash into pits or ponds on their properties, where it can percolate into waterways and groundwater or get carried by wind as carcinogenic “fugitive dust.”

Yet regulators have largely failed to control disposal of this material, which contains arsenic, lead and mercury, even though a person living near an unlined coal ash storage pond bears 2,000 times the cancer risk as those same regulators deem acceptable.

For decades, the coal and utilities industries and their allies in Congress have blocked attempts by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to create standards for disposing of coal ash. Finally, in 2015, the EPA succeeded in publishing regulations that mean utilities now have to take costly measures to dispose of coal ash, rather than leaving it in unlined ponds. But these standards exempt landfills—and that means that dumps across the country are increasingly being viewed as cheap, convenient dumping grounds for coal ash. In essence, the law created a new market for coal ash disposal at landfills, one that companies like Republic are eager to cash in on.

“Utilities are looking for various holes in the ground to dump coal ash, where it’s going to be cheap and unregulated,” said Lisa Evans, a coal ash expert and attorney with EarthJustice. “So they’re looking at municipal solid waste landfills.”

Last year, environmental groups, led by EarthJustice, called for the EPA to require landfills to meet the same standards that utilities have to meet under the new rules. Among them: better liners for the ponds, stricter monitoring, better siting and more public notification. Without those measures, they say, ill-equipped landfills could become as dangerous to the environment and public health as any badly managed coal ash pond. The EPA did not respond to the petition.

Because coal ash disposal was unregulated before the new rule—and because municipal landfills are exempt—neither the EPA nor the states have tracked just how much has ended up in landfills. But Broadhurst alone took in at least 800,000 tons of coal ash without the community ever knowing about it. And residents only found out because a newspaper reporter tracked down the numbers.

Some 15 months later, to the great surprise of the anti-coal ash coalition, the community’s campaign paid off. In April, Republic abruptly announced in an email that it was withdrawing its applications for permits that would allow it to haul coal ash into Broadhurst.

“I was puzzled. I just read it and read it, over and over again,” Riggins remembers. “I thought: Does this mean what it says it means? I started crying. I was just bawling.”

‘Ringing the Fire Bell’

In January of last year, Neill Herring, a Jesup resident and lobbyist for the Sierra Club, stopped by the squat, concrete-block offices of the Press-Sentinel, Wayne County’s twice-weekly newspaper, and told veteran reporter Derby Waters about an application by a company called Central Virginia Properties to build four rail lines on 250 acres adjacent to the Broadhurst landfill.

The purpose of those lines, according to the application, was to bring in as many as 100 rail cars of waste to the landfill every day, including “Coal Combustion Residuals”—or coal ash.

Waters did the math: 100 rail cars translated to a potential 10,000 tons of coal ash. Yet, Central Virginia Properties hadn’t informed anyone in the Wayne County government.

The Press-Sentinel’s newsroom—consisting at the time of a publisher who also wrote the sports section, two-part time reporters, an editor and the paper’s owner, W.H. “Dink” NeSmith—dove in. “We started ringing the fire bell,” NeSmith said. “In my 68 years, I’ve never seen so much upset.”

Over the course of the next year, the 6,000-circulation paper published more than 75 stories on the landfill, including three ad-free special sections about the dangers of coal ash. NeSmith fired off nearly 50 editorials and hired a squad of lawyers from Augusta to fight Republic.

“These waste management companies, they target poor, rural communities that are traditionally cash-strapped and don’t know much about the consequences,” NeSmith said. “They prey on communities like ours.”

Waters uncovered what Republic’s managers clearly hoped no one would: That Central Virginia Properties was a subsidiary of Republic, the nation’s second largest waste hauler. Republic, Waters learned, had quietly doubled the size of its property in Wayne County to more than 2,200 acres, of which 260 is now permitted for garbage disposal.

Waters also learned that Broadhurst had already taken in 800,000 tons of coal ash between 2006 and 2014 from a utility in Jacksonville, Fla., 90 miles to the south. The Atlanta-Journal Constitution, soon after, found that Republic had reported to the state in 2012 the presence of two toxic heavy metals, beryllium and zinc, in monitoring wells at the landfill. But the state never told Wayne County officials.

Just as troubling was Waters’ discovery of a pair of agreements between Republic and the county, signed in 2005, that appeared to prevent the county from opposing any expansion at the facility—now or in the future. Under the agreement, opposition from county commissioners could prompt Republic to stop paying fees, which at about $750,000 a year are a major source of income for the county. The agreements appeared to tie the county’s hands and made officials reluctant to speak out against Republic.

The Press-Sentinel’s journalistic assault lit up this largely Republican community. (Nearly 80 percent of voters cast their ballots for Donald Trump last year.) Neighbors showed up at county-wide prayer services and meetings so crowded that dozens had to stand outside. County residents enlisted the help of state lawmakers and environmental advocates from Georgia and beyond.

“Nobody paid attention to the landfill,” Riggins recalled. “When this came out, people were shocked, and when they learned about the contracts, people felt angry because they felt powerless.”

Riggins organized a 27-person committee whose members had an array of relevant skills: a biologist, an expert on environmental impact reports, a social media whizz, a cartographer. They studied maps, enlisted support from fishing groups down river, and even identified endangered plant species in the area, eager to do anything they could to create red tape for Republic.

Meanwhile, environmental groups from around the region, as well as lawmakers, took note of the controversy. U.S. Sen. David Perdue, a Republican from Glynn County, downriver from Wayne County, pushed for a public meeting. The Army Corps of Engineers, which was reviewing the proposal to expand the Broadhurst rail yard, extended its public comment period twice.

By the summer of 2016, the community felt like its campaign had gained some momentum.

‘Why Wouldn’t You Want to Preserve This?’

Dink NeSmith is a connected man—the kind who goes quail hunting with governors and rides on corporate jets with the state’s richest citizens. He is also a green-minded businessman and president and part owner of Community Newspapers, Inc., which operates about two dozen newspapers throughout the South. He helped usher a prison into the county because “it’s a growth industry without a smokestack.”

“I’m proud to be a businessman, but you can’t sacrifice the environment for money; there’s got to be balance,” he said. “We want jobs. Prostitution’s a job. It’s just not the job we want.”

Thirty-five years ago, with NeSmith’s publishing star on the rise, he bought 131 acres of land next to the Altamaha River, eventually piecing together a 7-square-mile property of swampland and pine forests. Much of that is in conservation easements now. “I want to leave my kids something they can’t buy at a Wal-Mart,” he said.

Southeast Georgia’s web of wetlands, creeks and rivers eventually drains into the Altamaha and Satilla rivers. It’s a soupy, moss-dripped landscape, connected in a beautiful but vulnerable way. What happens at the local landfill happens, potentially, to NeSmith’s land, too.

To NeSmith, a scripture-quoting Southern Baptist, this land is church. He often spends the night on his property in a metal-roofed cabin made of cypress pulled from the swamp and watched over by a stuffed bobcat. One day this spring, NeSmith climbed into a Jon boat docked near the cabin, just as the Tupelo trees were about to bloom. He rode along the swamp, leading to the Altamaha and the Atlantic Ocean 40 miles away. Snakes draped from tree branches and white ibises lit up the grey-green canopy.

“Why wouldn’t you want to preserve this?” NeSmith wondered.

NeSmith, fighting to protect God’s swamp, appealed to former President Jimmy Carter. “This is a classic David-and-Goliath battle, and we desperately need you to protect Coastal Georgia,” NeSmith wrote.

Carter responded by appealing to Bill Gates, whose private investment fund owns more than 90 million Republic shares—and, yet, has committed billions of his own fortune toward clean-energy solutions. “This will adversely impact some favorite streams of mine, where my father took me fishing many years ago,” Carter wrote, by hand, on his personal stationery. Gates wrote to Carter that he had asked Republic to “look into the matter.”

NeSmith also began taking pledges for a legal battle, pulling together more than $1 million, including money of his own. “We geared up for a fight,” he said.

Threats and PR

Republic, based 2,000 miles away in bone-dry Phoenix, put up a fight of its own.

The company dispatched engineers and other officials to the county. In a letter, Republic warned that any legal challenges would be fruitless. “Such a course of action,” Republic’s area president wrote, “would put at risk the substantial benefits to be received by the county and its citizens from the operation of the Broadhurst Landfill …”

At the same time, Republic mounted a public relations campaign, inviting members of the community to “open houses” with activities for children and free food. Republic gave tours of Broadhurst to reporters, showing off the sophisticated, state-of-the-art operations of a modern-day landfill. The company demonstrated how wells are monitored, how 27,000 gallons of leachate—liquid from the waste and rainwater, also called “garbage juice”—is collected, stored and treated, and how a layer of dense polyethylene lines the waste “cells.”

According to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources’ Environmental Protection Division (EPD), there are 48 lined municipal solid waste landfills in Georgia, Broadhurst among them. That liner is required by federal law for these “Class D” landfills, which can take in both industrial and municipal waste.

Chip Lake, a spokesman for Republic, said that the waste sites are also underlain with two feet of clay, in addition to the liner. The site is fully compliant with all disposal requirements under federal and state laws, Lake said.

Chip Lake, a spokesman for Republic, said that the waste sites are also underlain with two feet of clay, in addition to the liner. The site is fully compliant with all disposal requirements under federal and state laws, Lake said.

Critics doubt whether a nickel-thin liner can keep the various toxic constituents of coal ash from reaching waterways. Neill Herring is one. “It’s a piece of plastic that’s about one-sixteenth of an inch,” he said. “Anyone who thinks that’s going to survive over time is an idiot.”

The location of the Broadhurst landfill is critical. It may be hidden by spindly Georgia pines, but that makes no difference to waters flowing around and underneath it.

At a recent No Ash At All gathering, Steve Larson, who is a biologist and recently ordained Episcopalian priest, asked a scientific question in ministerial tones. “There is no more productive area of land than an acre of estuarine marsh, and whatever may happen may not affect anyone in this room in our lifetime,” he said. “It’s not that we don’t need to store this material, but do we need to store it at the headwaters of two pristine, major estuarine rivers?”

A Flood of Ash

In 2008, a dike gave way at the Kingston Fossil Plant, a power plant in Harriman, Tenn., sending as much as a billion gallons of coal ash sludge into nearby rivers and bringing the public’s attention to the dangers of coal ash for the first time. During the cleanup process, millions of tons were shipped to Uniontown, Ala., ending up in the landfill of a poor, majority-black community.

The Kingston disaster gave environmental groups ammunition to ask the EPA for stronger protections. Coal ash has never been declared a hazardous waste, thanks to a 1980 amendment, sponsored by the coal and utilities industries’ allies in Congress, which created an exemption under federal law.

“Coal ash was never regulated by the EPA even though, over the course of many decades, this toxic waste had been dumped into the backyards of coal plants,” explained Dalal Aboulhosn, deputy legislative director of the Sierra Club. “We had been pushing EPA to regulate this as hazardous waste, which is a legal definition that brings the highest standards for disposal. But that fell on deaf ears, until Kingston.”

In 2015, nearly seven years after Kingston, the EPA released a final rule, outlining specific requirements for coal ash disposal at utilities. The new rule requires a utility to close any pond that’s leaking dangerous materials into waterways, to line new coal ash ponds and to place them away from waterways or sensitive areas such as wetlands.

Environmental groups were disappointed because the agency did not declare coal ash hazardous waste and the new rule exempted municipal landfills. That made landfills appealing destinations for coal ash, especially from power plants in areas with high water tables or porous rock.

“There are a lot of plants in Tennessee and Florida that are going to have trouble meeting the location restrictions under the coal ash rule, because of the hydrology of the area,” said Amelia Shenstone, a coal ash expert with the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. “If that is determined—that the ash can’t be safely stored—they’re going to relocate it, and potentially pretty far away from where they are.”

The new regulation, in essence, created a compliance-driven market that companies like Republic saw as a business opportunity.

“These landfill operators are eager to get the tonnage. They assure everyone that EPA says it’s not hazardous, so it must be okay,” said Herring. “The rules that apply to the people that make the coal ash—that are familiar with its characteristics—those rules don’t apply to landfills. That’s a problem. That’s a serious problem.”

More than half of the coal ash generated in 2015 was recycled, mostly into concrete, a practice most environmental groups support. The great bulk of the ash that’s not recycled ends up stored in ponds at the utilities. Roughly 40 percent of those ponds are in the southeast.

It’s unknown how much coal ash has been dumped in Georgia’s municipal landfills, because until recently state law didn’t require disclosure of what was being dumped, only what state it came from. Last year the state issued a new rule requiring any landfill that accepts coal ash to develop a management plan, which includes recording how much ash it takes in and from where, according to Jeff Cown, a spokesman for the state EPD. The EPD doesn’t dictate what those plans should include, though it can reject a plan as incomplete.

Environmental groups say that’s a huge loophole. They also say that the management plan won’t automatically trigger public disclosure, which means communities may not find out if coal ash is being dumped in their landfill.

Under the federal EPA’s new rule, states are required to come up with plans for disposing of coal ash at utilities’ sites. Georgia Power, the state’s largest utility, has said it will close and excavate 29 of its ash ponds, but has not said where it plans to put the ash. “They’ve been deliberately vague,” said Peter Harrison, an attorney with the Waterkeeper Alliance. “When they had to post these closure plans, things had already started boiling over in Jesup.”

In other words, the state’s biggest power company will have a lot of excavated coal ash on its hands, hasn’t said explicitly where it’s going—and municipal landfills like Broadhurst have a lot of room to take it in.

Against All Odds

A little less than 15 months after Wayne County residents found out that Republic was planning to turn their community into a coal ash dumping ground, they were hit with a happy surprise.

In an email sent to county officials with the subject line “Broadhurst Landfill Announces Its Latest Good Neighbor Plans,” Republic said it would withdraw applications for state and federal permits that would have allowed the dumping plans to move forward.

The following day Republic sent three letters—one to the Army Corps of Engineers in Savannah, two to the state Environmental Protection Division—saying it would withdraw its permit applications. Republic officials told NeSmith they backed off because, in his words, “we the community, we the newspaper, were willing to tie this up legally for a long time.”

Republic officials said they wanted to engage the community before making any next moves, including the renegotiation of the 2005 agreement that appeared to tie the county’s hands.

“While we continue to believe that the project was sound,” Republic spokesman Lake wrote in an email, “we voluntarily withdrew these permits in an effort to foster a better atmosphere for discussions with the local leaders.” Lake said the company has no plans to dispose of coal ash at Broadhurst in the near future.

Wayne County received the news with relief and applause. “Derby should get a Pulitzer,” said Cynthia Morris, a member of No Ash At All.

He didn’t. But the Press-Sentinel did win 18 Georgia Press Association Awards for its coverage.

“The Press-Sentinel did what we believe a newspaper’s supposed to do,” NeSmith said. “If you can’t stand up for the places and the people you love, what kind of newspaper, or person, are you?”

Riggins agrees the battle is over, but suspects the war will continue. Republic’s top brass could still build the rail line even if the county manages to extract an agreement saying they’ll never bring in coal ash. And that’s doubtful.

“A lot of people come up to me and say: ‘Congratulations! Y’all won!,'” Riggins said. “And I say, we don’t have anything in writing. I’ve become more cynical—and I’m trying to fight that. But I was terribly naive. I even thought in the beginning all we’d have to do is say no.”