Above Photo: Belinda Joyner, a critic of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, speaks at a recent public hearing.

Google is blocking our site. Please use the social media sharing buttons (upper left) to share this on your social media and help us break through.

On September 15, 1982, high-profile protests over the siting of a toxic waste dump in Afton, North Carolina – an overwhelmingly African American town an hour northeast of Raleigh – set in motion a wave of reforms to prevent polluters from targeting people of color and the poor.

Thirty-five years later, North Carolina advocates say the $5-billion Atlantic Coast Pipeline deserves its own place in the environmental-justice history books – a distinction they believe could be its undoing.

“It deserves its own claim to shame,” said Therese Vick with the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League.

Backed primarily by Duke Energy and Dominion Resources, the project would transport 1.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day from the Marcellus Shale region to Virginia and North Carolina, hugging the I-95 corridor before ending in Robeson County.

In all but one county along the pipeline’s 180-mile route in North Carolina, African Americans, Native Americans and those living in poverty make up a greater percentage of the population than the statewide average. More than a quarter of the state’s Native Americans live along the project’s path.

Despite flagging 71 percent of the census tracts along the North Carolina pipeline route for ‘environmental justice concerns,’ federal regulators have given the project the green light – a move scores of groups are contesting.

And with state officials yet to rule on any of the pipeline’s four required environmental permits, advocates say the project’s disproportionate harm to low-income, minority, and Native American communities should weigh heavily in their decision.

“This is such a huge environmental injustice,” said Vick. “It’s not in question.”

‘A dumping ground’

For critics, the clearest case of environmental injustice lies in Northampton County, where a compressor station is slated to squeeze natural gas from a 42-inch pipe into a 36-inch pipe at the Virginia border.

The station is characterized as a “small” source of emissions, but opponents say the state’s draft air quality permit doesn’t reflect spikes in smog-forming nitrogen oxide, benzene, formaldehyde and other pollutants that could harm public health.

A report issued this month by the Clean Air Task Force and the national NAACP notes that cancer rates – especially lung and bronchial, forms exacerbated by air pollution – are higher in Northampton than in the rest of the state.

In the census block group where the facility would be located, African Americans make up over 79 percent of the population, per comments from the Southern Environmental Law Center on behalf of the NAACP, the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network, and ten other groups.

The organizations point out the county is already saddled with other major sources of air pollution: a wood pellet facility, another compressor station, and a plywood mill, all within a seven-mile radius.

“It’s like: how much more can people take?” said Naeema Muhammad of the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network.

“I feel like they have taken this area for a dumping ground,” said Belinda Joyner, an organizer with Clean Water for North Carolina who lives in Northampton.

One outcome of the decades-old environmental justice battle is the state’s “environmental equity” initiative, which requires it to consider cumulative impacts from all the facilities in the area before issuing an air quality permit for a new one.

Advocates are seizing on this policy to justify their request that state regulators withdraw the draft permit and conduct a more thorough analysis.

“The Environmental Equity Policy recognizes the potential for disproportionate environmental burdens to be imposed on low-income communities and communities of color,” write the groups, which also include the Haliwa-Saponi Indian Tribe.

‘Failed to take a hard look’

Pipeline foes point to similar problems with a proposed compressor station in Buckingham County, Virginia. A door-to-door survey by the Friends of Buckingham County found the community closest to that facility is 85 percent African American or bi-racial; the commonwealth as a whole is 19 percent African American.

The compressor stations are just two examples of how the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has abdicated its duty under the law to consider the pipeline’s impacts on environmental justice communities, advocates say.

“…the Commission failed to take a hard look at the harmful effects and enhanced risk the [pipeline] imposes on low-income communities, communities of color, and American Indian tribes,” reads a petition to FERC to rehear the pipeline case, filed earlier this month by the Southern Environmental Law Center and Appalachian Mountain Advocates, on behalf of more than 20 organizations.

The document continues: “When federal agencies fail to consider adequately how their decisions can harm these vulnerable, already over-burdened populations, the central goal of [the National Environmental Policy Act] is thwarted.”

The groups argue regulators erred by comparing census tracts along the pipeline’s route to their parent county only, and not also to the state as a whole. Yet even this county comparison shows communities of color and the poor could bear the brunt of the project’s risks – a possibility not reflected in FERC’s assessment.

The agency’s statistics show that 36 of the 42 affected census tracts in North Carolina have higher percentages of at least one minority community than the surrounding county. Just over half have greater portions of poor people.

An analysis from the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs shows that Native Americans comprise 13 percent of the population in the census tracts in the path of the project – compared to 4 percent in the counties on the route.

Yet FERC failed to formally confer with these sovereign communities, another dereliction of duty, says the rehearing request.

“They tried to say they consulted with tribes along the route,” said Robie Goins, a member of the Lumbee Tribe in Robeson County, where Native Americans constitute nearly 40 percent of the population. “They really didn’t.”

According to the petition, zeroing in on census block groups – which are smaller than census tracts – also shows people of color living disproportionately close to the pipeline, and more prone to suffer or be killed in the unlikely event of an explosion.

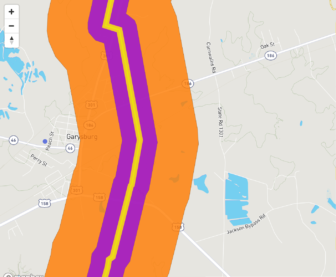

Using a formula developed by oil and gas engineering company C-FER Technologies, Clean Water for North Carolina calculated the “high impact area” to be within 943 feet of the pipeline – a radius nearly 300 feet larger than that assumed by Atlantic.

That puts several blocks of Garysburg, North Carolina – which is 95 percent African American – in danger of severe injury and death or property damage if there is an accident. Dozens more blocks are within an evacuation zone that extends more than 3,000 feet.

In the face of all these data points, pipeline opponents along its route say they feel unfairly targeted.

“[The pipeline company] sees us as poor, uneducated, with very little political power, and with the inability to fight back,” said Barbara Exum, an African American from Wilson County who owns property in the pipeline’s path.

‘No better way to help poor people’

Duke Energy and other pipeline backers refute this claim – saying eastern North Carolina’s impoverished status is precisely why the region should embrace the project.

While most of the gas will be used in power plants and homes, boosters say, the amount leftover will supply new industries that can create badly-needed jobs for the region.

“The positive economic impacts of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline will be significant for eastern North Carolina and will improve the lives of thousands of residents,” Duke spokesperson Tammie McGee said in an email, pointing out that the state’s only other natural gas pipeline is the Transco line, nearly 200 miles west.

The argument has won favor with many economic development managers and local elected officials, including some African Americans – Fannie Green, a Northampton County commissioner, among them.

“There are lots of benefits to having this pipeline,” Green said at the compressor station hearing. “If I thought it was going to be a bad thing for Northampton county, I would be the very first person to say no.”

Those sentiments were echoed by project supporters, who made up more than a third of speakers that night.

“There’s no better way to help poor people than to give them a job,” said Tom Betts of Rocky Mount, a former economic development chairman.

‘Unless the talk is backed up by action…’

The Northampton County hearing wasn’t strictly required by law – but part of North Carolina regulators’ attempt to increase public input on the controversial pipeline.

“We’ve had a huge amount of…interest from our tribal governments and from many community groups who wanted to be sure that we took a careful look at environmental justice issues,” said Bridget Munger, a spokesperson for the Department of Environmental Quality.

Overall, DEQ’s request for input has generated nearly 24,000 comments, and hundreds have appeared at public meetings – most opposed to the pipeline. More than 8,000 weighed in on the compressor station permit alone, Munger said.

Almost to a person, pipeline opponents thanked DEQ for holding the Northampton hearing. Advocates are also careful to praise the agency’s intense scrutiny of the project.

But at the end of the day, they say what really matters is whether DEQ allows the pipeline and the Northampton facility to move forward as proposed. A decision on the latter is expected December 15.

“Meetings and inclusiveness are important, but environmental justice isn’t just about inclusiveness,” said Vick of the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League. “Unless the talk is backed up by action, I don’t know what it’s going to mean.”