Above Photo: Student protesters in Paris, May ’68.

Fifty years on, we need a return to the anti-imperialist ethos that enabled the activists of ’68 to engage in a shared struggle against a common enemy.

Members of the Weather Underground, a radical direct-action splinter group of the SDS.

In 1964, students at the University of California at Berkeley staged a sit-in at Sproul Hall to protest campus restrictions on political activism. Shouting through his bullhorn, Mario Savio, the leader of the Free Speech Movement, likened modern society to an unhearing, unfeeling, oiled machine that needed to be stopped.

There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part. You can’t even passively take part! And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!

Four years later, students the world over had seemingly made good on Savio’s words. In Italy, the occupation of the University of Turin in 1967 ignited a widespread student take-over of campuses in Florence, Pisa, Venice, Milan, Naples, Padua, and Bologna. By March 1968, the spreading disruptions had paralyzed the entire system of higher education in Italy. Tens of thousands of students went on strike; the universities were besieged or occupied; and professors faced locked rooms or empty lecture halls.

In 1968 in France, student protests began at Nanterre and soon spread to occupations throughout the French university system. The same year, German students occupied the Free University in Berlin and barricaded the entrances to campuses in Frankfurt, Hamburg, Göttingen and Aachen while high school and university students in Mexico occupied their school buildings under the slogan “We don’t want the Olympic Games, we want a revolution!”

In the United States, the 1968 occupation of Columbia University by the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was, within two years, replicated across the country as over 4 million students — joined by 350,000 faculty in over 800 universities — went on strike, taking over university buildings and burning down army recruitment offices. Between May 1 and June 30, 1970, nearly a third of all US universities witnessed “incidents which resulted in the disruption of the normal functioning of the school.”

Initially centered on campuses, students soon took their tactics outside the university to disrupt “business as usual” within society at large. In the United States, students blocked railroad tracks and city streets, and held sit-ins on America’s highways to engage stalled drivers in debates about the state of the nation — though how well this last tactic worked is open to some debate. Anti-war demonstrators chanting “Hell no, we won’t go!” occupied the Pentagon steps, blockaded draft-induction centers and obstructed draftees in attempts to arrest the movement of American bodies to fight the war in Vietnam. In May 1971, 35,000 anti-war protesters occupied West Potomac Park in Washington and announced that “because the government had not stopped the Vietnam War, they would stop the government.”

In 1966, student groups in West Berlin had blocked traffic by engaging passersby in long discussions. Two years later the German New Left was building street barricades and overturning the Springer publication’s delivery trucks in order to physically arrest the distribution of false reports of their activities. In 1968 in France, the government crackdown on the universities led to the construction of barricades in the streets of Paris and the spread of the occupations to factories that paralyzed the country for the better part of May and June. All told, between 1968 and 1970 alone, tens of millions of students and workers across the Atlantic, en masse and spontaneously, shut down thousands of universities and factories, and took effective control of their places of study and work.

NEITHER MARX NOR COCA-COLA

Almost immediately, the non-violent disruptions of the New Left attracted intense criticism. The leftist militant Pierre Goldman claimed that New Left students were “satisfying their desire for history using ludic and masturbatory forms.” Left-wing critics excoriated the student protests: “For a number of weeks, [the rebels] were the masters, not of French society, nor even its university systems, but of its walls.” To many of an older generation, the imagination had seized power in 1968 — but it was only an imaginary power. “Because they no longer wished society to be a spectacle” critics damningly continued, “they mistook a spectacle for society.”

Even the sympathetic Sartre remarked that “a regime is not brought down by 100,000 unarmed students, no matter how courageous.” This understanding of the New Left as engaged in a war between an all-powerful military state and powerless students adrift in a purely symbolic and performative realm has been a near constant refrain over the past half century.

The ghost of Lenin drools over these and countless similar comments that judge 1968 by its potential to appropriate political or economic power. Like Lenin, they view the New Left through the eyes of the state, as something that did or did not pose a threat to its existence. From this vantage point, as Kristin Ross writes in May ’68 and its Afterlives, “people in the streets are people always already failing to seize state power.” Such views cannot help but see 1968 as the failed, symbolic and masturbatory reenactment of what workers had attempted before. Or what British journalist David Caute described as the “playground stuff” of middle-class kids “enacting their nursery rebellions.”

By the 1980s, critics from the old left were joined by other commentators. These newcomers — including the aging participants of 1968 itself — described the New Left as a “generational” or “cultural” revolt; as the birth of an era of personal expression that was soon recuperated in the service of consumer capital; and, most recently, as enabling the communications “revolution”epitomized by the internet. In their celebration of youth pressing up against staid barriers and embrace of unfettered personal creativity, each of these newer interpretations simultaneously elevated individuals and individualism while disavowing the collective political essence of 1968. While the old left claimed that “nothing happened” in 1968, these more recent interpretations assert its teleological connection to what we have become today.

Both fundamentally misconstrue what many activists were attempting to do. Lost in these critiques is the collective, global, anti-imperialist, emancipatory politics of 1968. Civil rights and black power activists; students in Paris, Mexico City, Berlin, Berkeley, and New York; and feminists self-identifying as Third World women articulated an anti-imperialist politics that expanded the existing economic understanding of oppression to include foreign policy, domestic social relations and individual consciousness. The anti-imperialism of 1968 and the New Left provides some important lessons for the politics of liberation today.

A POLITICS OF ANTI-IMPERIALISM

The year 1956 was key to the emergence of the New Left. Within the span of a few months beginning in late September, the British and French invaded Egypt to reassert Western control over the Suez Canal, the French social-democratic government pursued a brutal crackdown against Algerian freedom fighters in the Battle of Algiers, and the Red Army’s tanks rolled into Hungary.

These interventions were a wake-up call for many on the left, exposing the imperial violence of both the USSR and the West. A decade earlier, Frankfurt School theoreticians Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer claimed in The Dialectic of Enlightenment that “the fully enlightened world radiates disaster triumphant.” They argued that the scientific and managerial administration of society, rather than guaranteeing human liberation, had led to the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Now it seemed that wherever the left looked, the myths of technocratic and rational progress promoted by their own societies shattered against the harsh reality of Soviet tanks, napalm and very real threat of global thermonuclear Armageddon.

The 1960s brought these horrors into sharper relief. America’s war in Vietnam, a failed intervention into Cuba, the normalization of French torture in Algeria, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the West’s military and political support for repressive regimes in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East all underscored the imperial oppression occurring along a newly imagined North/South Axis.

However, unlike the complacency of the European and American left, the Third World was fighting back. In Cuba, Algeria and Vietnam, ordinary men and women had taken up arms to disrupt and remove imperial regimes from their countries. These Third World liberation struggles, particularly the resistance of the Vietnamese people to foreign domination, catalyzed the birth of the New Left throughout the Atlantic world. From its beginning, the New Left was internationalist to its core, drawing inspiration, tactics and subjectivities from the writings and struggles of Third World revolutionaries.

The guiding principle of this New Left subjectivity was anti-imperialism. They saw the world governed by an imperial authority, a global, unfeeling, unhearing machine which mobilized bodies and created desires to simultaneously buy its products and carry out its genocidal policies. SDS member Tom Hayden stated as much regarding the 1968 occupations of Columbia University, “the Columbia Students were taking an internationalist and revolutionary view of themselves in opposition to imperialism.” They aimed “to stop the machine if it cannot be made to serve human ends.”

Though expressed in many different forms, the New Left shared the feeling that the existing organization of human beings — how they related to one another, the ways they spoke, what they saw and desired — was a mechanism of social control. For New Left activists, these more subtle mechanisms worked hand-in-hand with explicit state and economic oppression to colonize the lives and minds of humans in “post-industrial” society. As Eldridge Cleaver of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense put it: “People are colonized, oppressed and exploited on all levels. Intellectually, politically, economically, emotionally, sexually and spiritually, we are oppressed, exploited, colonized.”

The broader critique of imperialism is crucial to understanding the politics of the New Left. For the New Left, the social order was not simply in the wrong hands — something that could be reformed or seized — but itself suspect. Anti-imperialism, in this sense, meant neither the modification nor the seizure of power but rather, and more profoundly, the destruction or devolution of it. As Italian student activist and later cultural historian Luisa Passerini observed in Autobiography of a Generation: Italy 1968, “we realized that, notwithstanding its fascination, the idea of an assault on the Winter Palace was archaic.”

The New Left, whether attacking a racist or patriarchal system, the Vietnam War or the university’s complicity in it, intended their political action to either withdraw from or completely irrupt the oppressive movement of the world around them. According to a Berkeley student leaflet, “we are not intent on petitioning leaders to take action on our behalf. We are no longer interested in protesting someone else’s politics. Reconstitution is about making our own politics.” The popular slogan of the French student revolt echoed this sentiment: “We won’t ask/We won’t demand/We will take and occupy.”

For naïve students to militant groups on both sides of the Atlantic, politics became less about making claims for inclusion or reform and increasingly about a total repudiation of the socio-political system. As the Yippies provocatively claimed, “we are not protesting ‘issues’; we are protesting Western civilization. We are not hassling over shit so that we can go back to ‘normal’ lives: our ‘normal’ lives are fucked up!” Or, in the words of Stokely Carmichael: “When you talk of Black Power you talk about bringing the country to its knees… of smashing everything Western civilization has created.”

Anti-imperialism opposed the encroachment of social control into the national, institutional, communal and individual domains of human existence. Instead it asserted the autonomy of these spheres, shaping efforts to stop the global war machine, arrest police intrusion into black neighborhoods, and redefine the social roles, perceptions and language of everyday life. Though the New Left used various terms for the imperial mechanisms of social control — “the machine,” “the establishment,” “the regime,” “the man” — the most common term was the police.

The police described its literal manifestation as well as the wider sense of modern society’s prescription and surveillance of the desires, horizons, occupational roles, and experiential universe of its members. Police and policing became central concepts in the New Left’s understanding of subjugation, a multi-layered target for the anti-imperialist politics they undertook to liberate their lives.

DISRUPTING AUTHORITY IN EVERYDAY LIFE

Professors, your modernism is nothing but the modernization of the police.

New Left activists across the Atlantic questioned the hierarchy and authoritarianism of liberal capitalist societies and disrupted the mechanisms of policing. As students formed a major contingent of the New Left, education was an early target. The student occupations connected the educational system within the universities to the university’s role within society. They disrupted examinations, the “control centers” of education that conditioned students to accept arbitrary authority and hierarchy within the classroom and acquiesce to it within society at large.

Students also challenged what they were being taught. They asserted that higher education had lost its critical function, becoming instead a site where future leaders were inculcated in the principles and rules of the social order. “University education has been reduced to the acquisition of technocratic skills…vocational training for the market researchers, personnel managers and investment planners of the future,” claimed Robin Blackburn in A Brief Guide to Bourgeois Ideology.

Students sought to disrupt this integrative function of education, to blockade the reproduction of society in its existing form. “We refuse the role assigned to us: we will not be trained as your police dogs,” wrote one student on the walls of Nanterre. As Alain Touraine, the French sociologist who witnessed firsthand the Nanterre insurrection, claimed, the 1968 student uprisings were about “transforming the relationship between the young person and society. He was being taught to enter society; he wished to learn how to change it.”

The student occupations and strikes that resulted in blockaded or empty classrooms were accompanied by efforts to revamp the higher educational system. Counter-curricula, alternative education courses and “critical” or “free universities” were often launched during or shortly following student strikes and occupations. First proposed and put into practice by the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley, by 1969, the Free University of Berkeley (FUB) offered 119 courses with such titles as the “Dialectics of Alienation” and “Revolutionary Thought and Action.” By 1970 there were 300-500 Free or Critical universities in the US with an estimated 100,000 students having taken one or more of their courses.

During the occupation of the University of Trento in northern Italy, insurgent students published a counter-curriculum challenging both the form and content of education administered by the university. A year later, the same groups circulated “The Manifesto for a Negative University,” a blueprint to radically reshape the university from an instrument of class domination to one of liberation. By 1968, Free Universities had been established in England, West Germany, France, Canada and the Netherlands. Throughout these counter-institutions, academic vocabulary was stripped of its “false neutrality” and radically moralized. As one French student wrote on the walls of the Sorbonne: “When examined, answer with questions.”

The hierarchical and authoritarian nature of education reflected the society that had created it. The larger problem for the New Left was the colonization of everyday life. First and foremost, there was the literal presence of the police, encountered by the white New Left in the form of the national guard or riot squad, and by Blacks daily as the street cop in their communities. In this context, decolonization meant confronting the authority the police wielded over human lives. “Liberate the Sorbonne from police occupation!” became a key demand of the French student uprising in 1968, one soon to be replicated across universities in Europe.

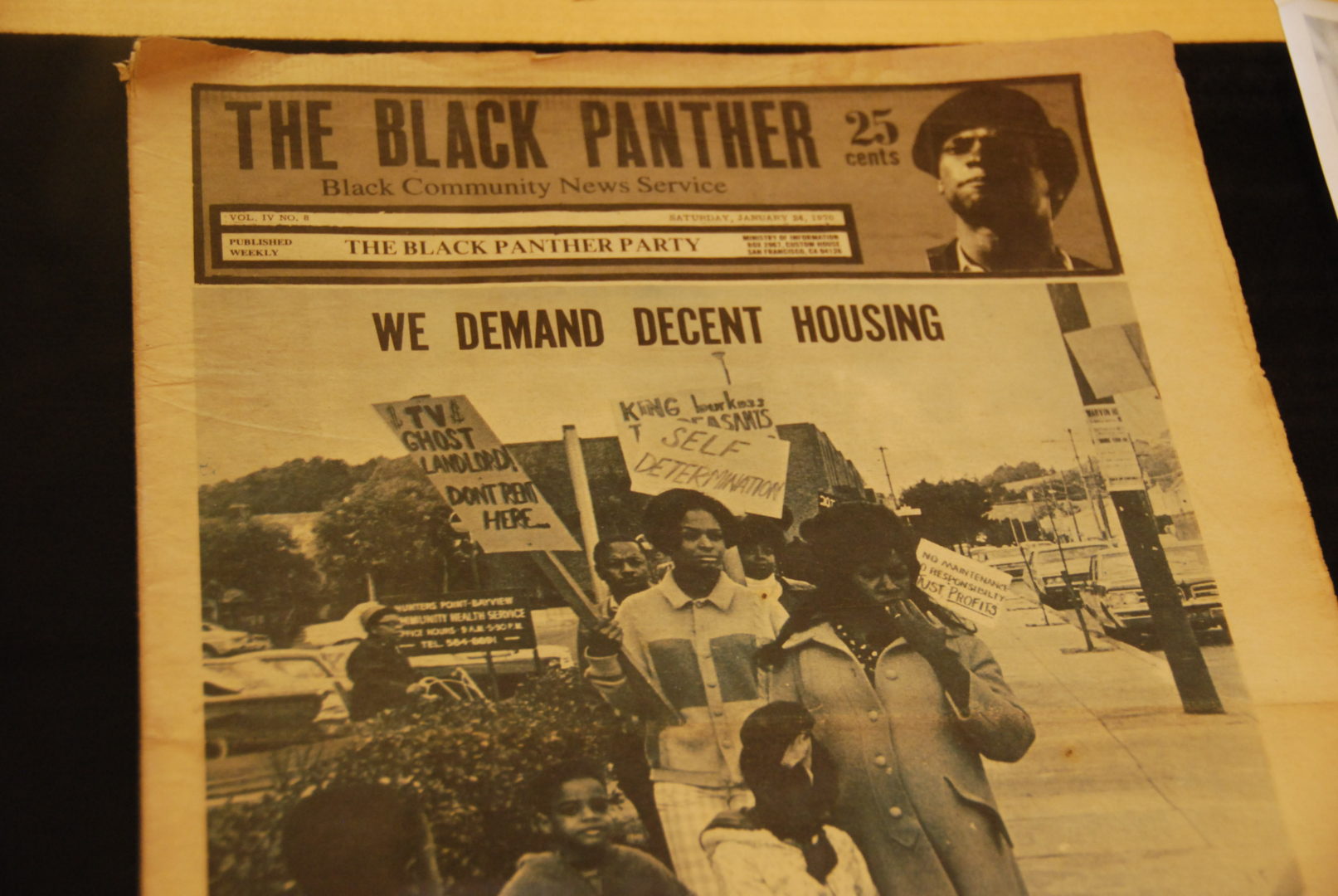

In the United States, decolonization was the explicit intent for the 1966 formation of the Black Panther Party, whose armed patrols shadowed law-enforcement officers, disrupting their attempts to racially police the “Black colony.” Significantly, their projects of neighborhood decolonization embraced the full gamut of anti-imperialist politics, from confronting the reign of predatory slum lords — a project also taken up by the Latino Young Lords of Chicago and New York — to burning draft cards, refusing to “fight and kill other people of color who…are being victimized by the white racist government of America.”

For other, mostly white and educated, members of the New Left, the police became a synecdoche for the social order in its entirety, a generalized epithet for authoritarian tendencies within society and the individual. Through this equation, the New Left marked authority itself as fundamentally anti-social. For the most part, the white New Left preferred — and had the luxury of — insolence over violent confrontation as a way of disrobing vested authority.

The first principle of the Antiauthoritarian Manifesto of the Artistic Avant-Garde, issued by the German collective Gruppe Spur in 1961, stated that: “Whoever does not see politics, government, church, industry, military, the political parties and social organizations as a joke has nothing to do with us.” Yippie Jerry Rubin, in his three appearances before the House Un-American Activities Committee, dressed as an American Revolutionary War soldier, a bare-chested armed guerilla and Santa Claus. Even Eldridge Cleaver, who opted for a more militant approach, saw the merits of insolence. “A laughed at pig is a dead pig,” he claimed, “barbecued Yippie style.”

These provocations toward vested authority were part of a larger project to disrupt the habituated behaviors and norms of modern society, the self-policing that enabled the smooth operation of capital. At the forefront of such initiatives was the small group of artist/activists that formed the Situationist International (SI). For the situationists, the Marxian economic concepts of alienation, reification and commodity fetishism reached beyond the economy to colonize every aspect of human existence, preventing authentic encounters among human beings.

To counter what they termed the “society of the spectacle,” the SI constructed public disruptions to jolt human beings out of their uncritical submission to consumer capitalism. Called “situations,” these brief moments revealed the colonization of everyday life by interrupting its mechanisms and flows. For the Belgian SI theorist Raoul Vaneigem, interruption was an essential step towards liberation: “People who talk about revolution and class struggle without explicitly referring to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about the refusal of constraints — such people have a corpse in their mouths.”

The often playful, theatrical disruptions of everyday life were adopted by many New Left groups. In Amsterdam, the Dutch Provos wreaked havoc on rush hour traffic by releasing thousands of chickens onto the streets while students at the University of California, Santa Barbara treated the main road leading into campus with lard, bringing traffic to a standstill. In 1970, over 1,000 students at the University of Connecticut walked into a ROTC building armed with brushes and painted the walls with flowers, cartoons and peace symbols. The Yippies brought panic to the New York Stock Exchange by throwing money onto the trading floor, and staged a “yip-in” that shut down Grand-Central Station before being brutally dispersed by the police.

In both these events, Yippies took aim at the city’s most famous sites of circulation, momentarily disrupting the flow of financial capital and human beings within the economy of movement. The point of such disruptions, as the West German Situationist group Subversive Aktion proclaimed, was to “interrupt the influences on the individual posed by society, allowing them to pause and reflect so that they could define themselves independently from authority.”

DECOLONIZING THE SELF

A cop sleeps inside each one of us. We must kill him.

“The consumer economy has introjected into the very nature of man aspirations and patterns of behavior that ties him libidinally and aggressively to the commodity form,” the leading theoretician of the New Left Herbert Marcuse wrote in An Essay on Liberation. “It instills the need for possessing, consuming, handling and constantly renewing the gadgets, devices, instruments and engines offered to and imposed upon the people.”

For Marcuse, this “voluntary” servitude, so internalized as to have become second nature, militated against any change that could disrupt it. Within late industrial capitalism, the social roles, experiences, ambitions and desires of the individual had been so colonized by consumer capitalism that humans were not even aware of their subjugation. The things we wanted, saw, spoke and felt imprisoned us within a society not of our making. In short, we had become our own police.

One solution was to drive a wedge between the individual and the administered society, to disrupt the mechanisms by which human beings internalized its worldview as their own. “To call into question the society you ‘live’ in,” read one May 1968 slogan, “you must first be capable of calling yourself into question.” The Yippies echoed this sentiment in the United States: “[We] believe that there can be no social revolution without the head revolution and no head revolution without the social revolution.” Activists targeted what they believed to be the two main mechanisms of the individual’s colonization: language and perception.

“We live within language as within polluted air,” Guy Debord wrote. “The problem of language is at the heart of all struggles between the forces striving to abolish present alienation and those striving to maintain it.” A staple critique made by the New Left was how speech had become a means of colonizing and policing the population. Activists saw two forms of linguistic colonization: an individual’s uncritical reproduction of words — and thereby concepts — necessary for the war and consumer machines, and the sterilization of once subversive speech now reincorporated into mainstream society — a “recuperation” that took place increasingly through product advertising: A Revolution in Motor Oil!, etc.

Word play and reversals of meaning interrupted the individual’s uncritical internalization of the language of the social order. These tactics were evidenced across the New Left, from the hippies’ “flower power” of placing flowers in the gun barrels of soldiers and police, to the Black Power slogan “Black is Beautiful,” which disrupted centuries of the Western concept’s association with the color white. Disruptive language was employed to delegitimize authority, as when the Black Panthers called elected officials pigs and translated their speech as “oink oink.” It was also used to discredit establishment phrases of submission such as “be realistic,” to which the French 1968 uprising famously appended “demand the impossible.”

As Stokely Carmichael once put it, “we shall have to struggle for the right to create our own terms through which to define ourselves and our relationship to the society, and to have these terms recognized.” This sentiment was shared by the leftist anthropologist Michel de Certeau, who reflected of 1968 Paris in The Capture of Speech that, “we began to speak, as if for the first time. The previously self-assured discourses faded away and the ‘authorities’ were reduced to silence.”

Perhaps more fundamental than language in the policing of the self was perception. Many strands of the New Left thought that society, particularly the consumer economy, had colonized the primary sensations, controlling what could and could not be seen, felt and heard in order to move its goods. “In the decor of the spectacle,” a French situationist tagged, “the eye meets only things and their prices.”

New Left politics sought to decolonize the self by disrupting these fixed experiences, linking liberation with the dissolution of ordinary and orderly perception. For some, this was tied to the psychedelic drug culture that originated on the West Coast of the United States. In 1967, San Francisco hippies held a “Human Be-In” at Golden Gate Park, touted as a new medium of human relations where those gathered would dissolve their preconceived categories and simply be. Timothy Leary, speaking before a crowd of 30,000, told them to “Turn on, Tune in, and Drop out,” urging the use of psychedelics as a way to detach themselves from the existing conventions and hierarchies of society. To the extent that the “trip” allowed for the dissolution of the ego, it was one mechanism by which a wedge could be established between the individual and their colonization by society.

More sober New Leftists found similar mechanisms in the simple act of coming together. In the tens of thousands of spontaneously established committees, action groups, encounters, chapters, assemblies and proliferating “ins” that formed the organizational backbone of the New Left, humans put into practice (or at least did their best to put into practice) the very non-authoritarian society that they preached. Across the Atlantic, New Leftists rejected staid institutional structures — political parties, established unions, university governance — instead creating new forms that disrupted the organization of society into segregated spheres of existence.

“Bourgeois culture separates and isolates artists from other workers,” opened a statement by the art collective Atelier Populaire, who occupied the École des Beaux-Arts in May 1968. It “encloses artists in an invisible prison. We have decided to transform what we are in society.” Within these groups, people of different ages, different occupations and different experiences came into contact with one another, many for the first time.

In 1968 France, comités d’action sprung up in factories, neighborhoods, in high schools and on university campuses. By the end of May, there were over 420 such committees in the Paris Region alone. Direct democratic unitary base committees (CUB) in Italian factories created a new rank-and-file activism that led to the Hot Autumn of 1969 and radical experimentation in worker self-management. In the United States, the civil rights struggle and opposition to the Vietnam War occasioned thousands of action groups creating unforeseen alliances across different social sectors.

Within all these largely leaderless groupings, members stepped out of their pre-assigned roles, questioned what it meant to be a student, an artist, a worker and a woman, and why these roles took place at specific and segregated sites — the school, the factory, the studio, the home. The groups’ very existence disrupted the demarcation and regulation of who should be doing what, why and where.

A recollection repeated throughout the memoirs of New Left members is the sheer novelty and exhilaration of participating in these social collectives. Time and time again, they speak of the new experiences that came with being among different people, of overcoming a previous sense of alienation and passivity, of their senses being assaulted by the new sounds, sights and smells of a non-prescribed belonging. “We could see one another, touch one-another, and realized that we were not alone,” wrote Jerry Rubin. “Instead of talking about communism, people were beginning to live communism.” As a French student recalled:

By becoming a militant … I entered into contact with a bunch of other people, different from me socially … [We felt] the human warmth that existed between us. When you’re a militant, there is something that makes everything worthwhile, it’s to find yourself out and about some morning at 4:00am, when it’s beautiful out, with a common project that escapes other people, with this happiness of being somewhere where you shouldn’t be, a type of complicity.

In this sense, the anti-imperialist politics of the New Left were directed as much toward themselves as to the society around them. It allowed, as Marcuse claimed, “a break with the familiar, the routine ways of seeing, hearing, feeling and understanding things so that the organism became receptive to the potential forms of a nonaggressive, nonexploitative world.”

FIFTY YEARS ON…

Imperialism is alive and well today. By any measure, it is more entrenched and pervasive than it was in 1968. Its presence is differentially experienced in the neoliberal university, “natural resource” extraction processes, the surgical violence of drone strikes and kill lists, parallel CIA black sites in Thailand and Chicago, Fortress Europe and Trump’s great wall, and mass incarceration in the United States. The interconnection of its policing mechanisms, a key revelation of the New Left, is undeniable.

Today we know, to sample a few egregious examples, that the tear gas fired by riot police in Ferguson, Missouri, the West Bank, Greece, Chile, and Egypt, was manufactured by the US corporation Combined Systems Inc.; the surveillance corporation Tiger Swan, hired by Energy Transfer Partners in 2016 to monitor Standing Rock activists, had its beginning as a defense contractor in the second Iraq War; and US law enforcement officers regularly travel to Israel to receive “counter-terrorism” training.

Added to this interconnection is the increasing colonization of the social lifeworld, both in the form of overt regulations as well as their internalization. As the New Left was the first to point out, our voluntary submission to such micro-political policing is the necessary complement to the functioning of empire on the macro-political level. Over the past fifty years, this micro-management of daily life, the minute rules governing which people can do what where, has infiltrated the entire social fabric. Again, its effect are differentiated. The same lack of a trading permit that shuts down children’s lemonade stands in the United States, led, in quite a different context, to the confiscation of a Tunisian fruit seller’s produce cart, his subsequent self-immolation, and the spark for the Arab Spring.

More alarming than this bureaucratic overreach is the deference accorded it by populations in the United States and Europe. Passersby calling the authorities to take away children walking home from the park unattended. The acquiescence of many American communities to transforming their children’s schools into maximum security prisons. The complicity of white gentrifiers in the criminalization of Blackness. These are but a few of the more overt examples of how humans feel more comfortable inviting imperial authority into, rather than self-governing, their own communities. At its most personal, this invitation takes the form of psychic and physical self-improvement, the continuous self-investment and production of oneself to enhance our own diminishing marketability.

The politics of anti-imperialism have not fared so well. Over the past fifty years, progressive and leftist activism has increasingly fractured along invented lines of interest and identity and largely abandoned its internationalist character. This fracturing, dividing both the subjects of resistance as well as their enemy, suits imperialism perfectly.

The broad-based anti-imperialist consensus animating 1968 New Left politics allowed activists to identify their shared fight against a common enemy — one whose appearance varied, but whose operations were the same. It allowed them to connect the oppression of different national and sub-national communities, and then to move further and struggle against the interconnection of domestic policing with international warmaking. It allowed them to escape their individual isolation by talking and acting collectively. As importantly, it enabled them to draw connections across national and identitarian grammars of discontent.

There have been promising, if halting steps to re-establish this consensus, beginning with the global takeover of the squares in 2011. Here the shared form of the uprisings — occupation — as well as the anti-imperialist politics restructuring what there was to do in them, brought hitherto desperate revolts against dictatorship, austerity and the tyranny of the financial sector under a single banner of shared resistance.

Since then, smaller-scale fellowships have proliferated, including Brazilian-Turkish solidarity in 2013; #Palestine2Ferguson activism in 2014; and the hundreds of US army veterans who joined the uprising at Standing Rock in 2016, to name but a few. Reaching beyond the borders of interest, identity and nation, these humans recognized that they are engaged in a common global struggle against an imperial apparatus that has blurred all lines between internal policing and external “defense,” between the colony and the metropole.

Responding to queries over his identity, Subcomandante Marcos of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, once remarked:

I am gay in San Francisco, Black in South Africa, Asian in Europe, Palestinian in Israel, Indigenous in the streets of San Cristóbal, a whistle-blower stuck in the Department of Defense, a feminist in any political party, a communist in the cold war, a pacifist in Bosnia… a housewife at home on a Saturday night… a woman riding the subway by herself at 10pm, a peasant without land, an unemployed worker… a dissident in neoliberalism, a writer without books or readers, an unhappy student—and yes, a Zapatista in southeast Mexico. This is Marcos.

In his recognition of the interconnectedness of global struggle, the EZLN leader echoed the words of the 1968 French revolt whose striking workers chanted “Vietnam is in our Factories,” whose students screamed “We are all German Jews.” Now, more than ever, we need a return to this anti-imperialist ethos, one that speaks of the enemy in the singular and constructs a global resistance against it.