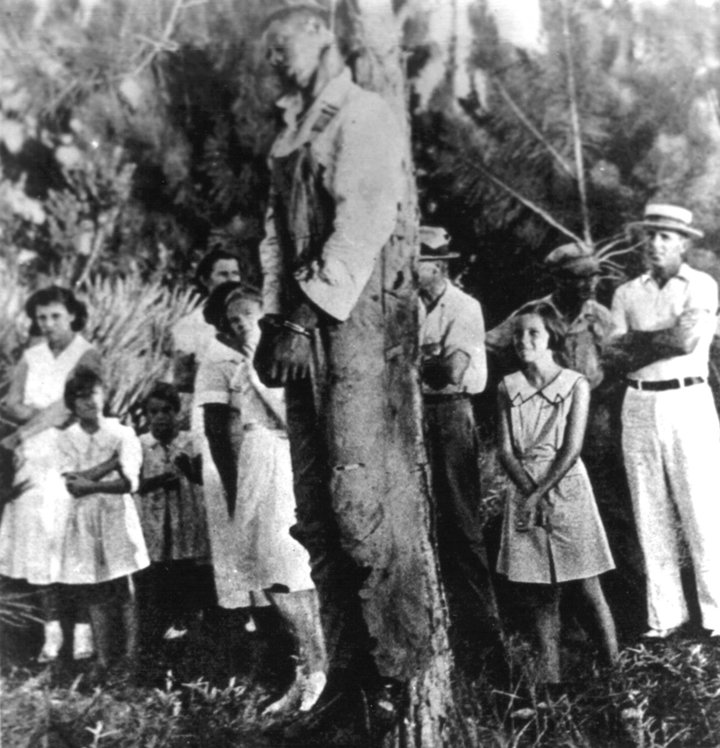

Above Photo: PHOTO 12/UIG/GETTY IMAGES. Rubin Stacy was lynched in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in July 1935.

A step-by-step guide to paying the descendants of enslaved Africans.

Let’s say you’re driving down the street and someone rear-ends you. You get out of your car to assess the damage. The person who hit your vehicle gets out of his car, apologizes for the damage and calls his insurance company. Eventually, you receive a check for the harm done.

Now, let’s say that for years, if not generations, your family and families like yours have been damaged by your country’s political and economic system — by law and widespread practice, with the intent of benefiting families not like yours — then the checks for the harm done would be called reparations.

Beginning with more than two centuries of slavery, black Americans have been deliberately abused by their own nation. It’s time to pay restitution.

Black activists and intellectuals have been making that point with increasing volume over the last few years, turning what was an obscure thought problem into a political issue. The question of reparations has even entered into the Democratic primary, with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) struggling to explain to black voters why he has built such a strong social justice platform on every issue but this one.

Sanders was put on the spot last month when a reporter asked him if he would support reparations as president. “No, I don’t think so,” he said, describing the likelihood of congressional passage as “nil” — as if those odds normally stopped him.

Every year since 1989, Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.) has introduced the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act. As the name indicates, H.R. 40 does not require reparations. It simply calls for comprehensive research into the nature and financial impact of African enslavement as well as the ills inflicted on black people during the Jim Crow era. Then, remedies can be suggested.

Every year, the bill stalls.

Fifty-nine percent of black Americans think that the descendants of enslaved Africans deserve reparations, according to a June 2014 HuffPost/YouGov poll. Sixty-three percent of black folks support targeted education and job training programs for the descendants of slaves.

Most other Americans still aren’t listening.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, perhaps the most prominent voice now pushing reparations, laid out why black Americans deserve even more than repayment for slavery in a sweeping 2014 article, “The Case for Reparations.” The exploitation didn’t stop with the Emancipation Proclamation, so any restitution must reckon with the discrimination that followed and deal with the living victims of these ills.

Last month, Coates criticized Sanders’ decision to shy away from the issue:

If not even an avowed socialist can be bothered to grapple with reparations, if the question really is that far beyond the pale, if Bernie Sanders truly believes that victims of the Tulsa pogrom deserved nothing, that the victims of contract lending deserve nothing, that the victims of debt peonage deserve nothing, that that political plunder of black communities entitle them to nothing, if this is the candidate of the radical left — then expect white supremacy in America to endure well beyond our lifetimes and lifetimes of our children.

Let’s change that — let’s bother to have the hard but necessary discussion of what black Americans are owed for what was taken from them. If reparations ever come, what would they look like?

1. Let’s Figure Out Who Deserves Reparations And Why

Simply put, reparations are due to the millions of black Americans whose families have endured generations of discrimination in the United States. Most black Americans count among their ancestors people who endured chattel slavery, the ultimate denial of an individual’s humanity.

William Darity, a public policy professor at Duke University who has studied reparations extensively, proposes two specific requirements for eligibility to receive a payout. First, at least 10 years before the onset of a reparations program, an individual must have self-identified on a census form or other formal document as black, African-American, colored or Negro. Second, each individual must provide proof of an ancestor who was enslaved in the U.S.

Why does this huge group of Americans deserve restitution? Because starting with slavery, the damage done was institutionalized and inescapable. Darity has created a “Bill of Particulars,” including such specific grievances as:

- The extended history of government-sanctioned segregation and other forms of racial oppression in the Jim Crow era

- Terror campaigns launched by the Ku Klux Klan, often in collaboration with government officials

- Post-WWII public policies that were designed to provide upward mobility for Americans but in practice did not include black people (such as the GI Bill)

- Redlining, which made home ownership a possibility for white people while shutting out black folks

- Ongoing discrimination against and associated denigration of black lives

Eric J. Miller, a professor at Loyola Law School, said the case for reparations starts with an honest accounting of the racism that black people have experienced. “Part of our history is our grandparents participating in these acts of terrible violence [against black people],” he said. “But people don’t want to acknowledge the horror of what they engaged in.”

White America built its wealth on those generations of legal and physical violence — a fact most white people today would rather not dwell on.

“People don’t want to believe that they got their gains in an ill manner,” Miller said. “The cognitive dissonance of learning that your property is got and preserved on the back of the misery of others is not an incredibly nice thing to live with. So people would rather discount it.”

But when the harm is great enough, it’s not enough to say you’re sorry and try to fix problems going forward. Germany made an effort to repay the Jews for the horrors of the Holocaust. Japanese-Americans were repaid for suffering in internment camps. Black Americans deserve no less.

This leads us to our next step.

2. So How Much Are We Talking About, Exactly?

No one really knows. (That’s part of the reason Rep. Conyers wants a commission.) But there are some numbers out there.

A 1990 study by Richard Sutch and Roger Ransom, professors at the University of California, Riverside, estimated that industries fueled by slave labor, like cotton and tobacco, made profits of $3.4 billion (in 1983 dollars) between 1806 and 1860. Darity has estimated that if you throw in an annual interest rate of 5 percent, that number jumps to $9.12 billion (in 2008 dollars).

Larry Neal, an economist at the University of Illinois, came up with an even higher number. His studies concluded that $1.4 trillion (in 1983 dollars) was owed to the descendants of enslaved Africans based on the compensation their ancestors did not receive for their labor between 1620 and 1840. With interest, that amounts to $6.4 trillion in 2014, according to The New Republic.

None of these numbers account for the physical and sexual violence inflicted upon enslaved Africans.

“I don’t think we really grasp quite how financially lucrative and important slavery was in America — including things like the illegal slave trade that continued after the Constitution forbade it,” Miller said.

The figures mentioned also don’t include compensation for housing segregation and other forms of racial discrimination in the years since slavery ended. Nor do they factor in the extent to which American industries have profited — and continue to profit — from exploiting low-income workers, many of whom are black.

How do we measure those kinds of losses — the chance at upward economic mobility that was stolen from millions? One way is to compare property values between majority-black neighborhoods that were redlined and white neighborhoods that were not — or property values within a single neighborhood before and after redlining.

Another way is to gauge lost educational opportunities. Good public schools are usually found in majority-white suburbs where people pay higher property taxes. Poorly performing schools are found more often in economically disenfranchised areas with larger black populations.

Bottom line: reparations are going to cost a lot of money. But America is a wealthy nation that can afford to pay for its misdeeds. For perspective, consider that in fiscal year 2014, the U.S. government spent $3.5 trillion, which is only 20 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product of about $17.5 trillion.

3. Now, How Would This Money Be Paid Out?

We could just divvy it up among eligible black Americans, but reparations advocates propose a more institution-based approach.

Darity suggests that financial payouts be divided between individual recipients and a variety of endowments set up to develop the economic strength of the black community. His model is inspired by Germany’s restitution payments both to victims of the Holocaust and to Israel.

The advantage of individual payouts, Miller notes, is that they maximize autonomy. But much of that money would land back in the white-dominated economy and “the one percent would become one percentier,” he said.

Hence the value of using a portion of reparation funds to create programs geared toward aiding black people in combating the damage of racism.

“One could think of Black America as being a community that could benefit from development investments,” Darity said. “So you could have a trust fund that was set up to finance higher education, [another] to create greater opportunities for opening one’s own business, and so forth.”

Darity envisions the U.S. government establishing and overseeing these programs. Although it might seem counter-intuitive to give this power to the very institution that committed so much discrimination against black people, the professor said the government should be heavily involved precisely because of that history.

“The U.S. government is the responsible party because of the entire legal apparatus that supported both slavery and, subsequently, Jim Crow and continues to permit ongoing discrimination,” he said.

Miller emphasizes that the reparations-funded programs must be fully accessible to and controlled by members of the black community.

“Unless institutions exist that are controlled by and accountable to the community, then the community will always be dominated, or prone to domination, by others,” he said.

4. But Will This Ever Happen?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Congress hasn’t even managed to pass H.R. 40. And that’s really no surprise since most Americans are not pushing their lawmakers to do anything on this issue.

Only 6 percent of white Americans support cash payments to the descendants of enslaved Africans, according to that HuffPost/YouGov poll. Only 19 percent favor reparations in the form of education and jobs programs, while 50 percent of whites don’t even believe that slavery is one of the reasons why black Americans have lower levels of wealth.

They’re wrong. “The connection between slavery and the pillars of American society are tight. There are no pillars of American society without slavery,” Miller said. “You might think about that even literally. The columns of the White House and the Congress were built by slave labor.”

To deflect discussing why reparations are needed, some people request a developed strategy for reparations or a detailed legislative proposal before they’ll contemplate the issue. The suggestion, in itself, fits into a tired line of thinking that victims of injustice must explain themselves fully — and convincingly — to the system that harmed them before any recognition is provided.

“These demands always struck me as akin to demanding a payment plan for something one has neither decided one needs nor is willing to purchase,” Coates wrote. As he has tirelessly reiterated, we must start with a robust discussion on why reparations are owed to black Americans.

If anything, the expansive U.S. history of anti-black racism is the deterrent — but letting that deter us today is itself anti-black.

This returns us to the criticism of Sanders. The symbolism of specifically calling for reparations matters. A white presidential candidate who vows only to fight police violence and other modern ills affecting black Americans is essentially urging that we put a bandage on past injustices without true reconciliation.

If we don’t look back and reckon with what has been done, there is no moving forward.