Above Photo: Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (detail). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

“The commons could be a means of breaking away from the reign of global markets.” Isles of the Left speaks with Massimo De Angelis about the inspiring experiences of commons in South America and Europe.

Raisa Galea: ‘Commons’ is a word on many lips, yet not everyone has a clear understanding of the concept. What is commons?

Massimo De Angelis: Commons is about sharing resources, collaborating and making decisions together without a top-down dictate. There is a variety of definitions which delve into what and how should be shared.

Elinor Ostrom, the Nobel Prize laureate awarded the prize precisely for her extensive work on the commons, defined it as common-pool finite resources such as grazing grounds, forests, coastal areas, rivers and so on. She argued that the best way to manage these natural ecosystems would be through a collective action of the people who use these resources, and not through state or market mechanisms. Unfortunately, today these common-pool resources are increasingly threatened by economic development that benefits only the few.

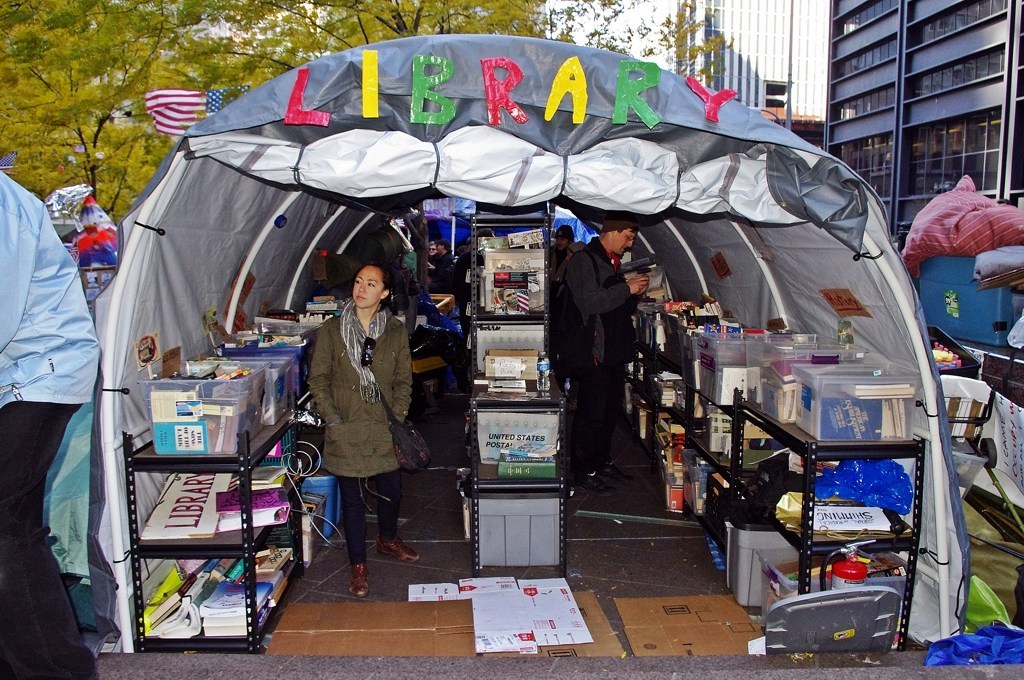

One of the limitations of Ostrom’s work is that, to her, only these types of resources could be defined as commons. However, there are plenty of examples demonstrating that people can collectively manage all sorts of things, not just the natural resources. At the People’s Library set up by the Occupy movement in New York, books—what Ostrom would call resources units—are also organised as commons. In principle, everything—natural and man-made resources and services—can be communalised, meaning they can be shared and governed by the community that handles them.

Another frequently mentioned concept of commons focuses on common goods—things that should be shared. Let’s take a specific example: in Italy we had a great movement demanding water to be declared as a common good. In 2011, the referendum to overturn the laws promoting water privatisation had an overwhelming success, but the movement was not prepared to take the matter further. The big question of how we manage a common good thus remained unanswered.

The third widespread related term is the common. In a nutshell, it is a principle of governance whereby we collectively set the rules and participate in decision-making.

Commons is about sharing resources, collaborating and taking decision together without a top-down dictate.

My take on commons is engaged with all the three definitions, but is broader. To me, commons are social systems based on three essential principles. The first is common goods which include physical resources, knowledge and skills to be shared; the second is a group of people who are ready to govern these assets and apply the skills collectively. These two elements are brought together by the process of ‘commoning’—doing things together, defining objectives and values, making decisions.

Commons, therefore, have a radically democratic principle at heart: they are organised bottom-up; all members have a say on how to relate to one another, how the available resources should be managed, what project to take next and what social or environmental justice issues to tackle. In commons, decisions are generally made by consensus. This form of governance enables them to formulate a common position without creating majority and minority camps. Clearly, this takes time, but diversity within the commons contributes to its resilience and vitality.

What is the difference between public and common? Say, there is a public garden next to my house. What would a common garden be like?

The major difference between public and common assets lies in who governs them. A public park or a street are managed by the state which has its own political priorities. For example, not only do the UK laws restrict or forbid foraging in a public park, but the state authorities do not even plant fruit trees there. Taking streets in London as an example of public space, we can observe that the pedestrian movements are restricted because the roads are taken up by car traffic, due to the rules defined by the authorities.

The commons are administered by a community of people who collectively decide what, how and when to produce within a given space.

The commons are not governed by the state. They are administered by a community of people who collectively decide what, how and when to produce within a given space. This community can have relatively open boundaries to allow public access to their space. These free access areas then become a space for brief communication and encounters—an introduction to the commons. Free access implies that a space is open to the public, but it does not involve taking care of it or any form of social participation in managing it. That is why every free access space needs to be overseen by a commons responsible for taking care of it.

When you talk about communities, what do you mean, exactly?

By community I mean a group of people united around a common project, defining objectives and values, making decisions and thus developing the commons systems.

The ability of communities to be both autonomous and resilient in relation to the pressure from the state and corporate interests is of strategic importance. For instance, radical commons, seeking to produce affordable organic food while sustaining an income for small-scale farmers, have to adapt to the legislation designed to suit the interests of large-scale farmers and agribusiness.

What about a society which might be already segregated along class and racial lines? There are wealthy gated communities on the one hand and ghettos on the other. It goes without saying that the assets of these communities, their capacity to manage resources and their political power are incomparable.

Correct. But the point of democratic organisation is to start from where you are and, by pooling resources together and collaborating, improve your condition. No matter how grave is the level of class and racial segregation, if everybody just stays passive, our collective power would be diminishing further. The commons is our chance to organise our struggle, improve our livelihood and take the decision-making power in our hands.

Here is a stark example. Back in 2004, I visited a few towns in South America and witnessed some of their anti-privatisation struggles. It was a massive movement! I could observe the difference between those people at the bottom of society who accepted any state authority’s initiative and those who decided to organise and reclaim their resources. The latter had an immediate advantage.

Rallying against the privatisation of electricity and the increase in electricity tariffs was a radical mass movement in South America. Simultaneously, there were initiatives for water privatisation and installation of water meters. The movement literally reclaimed access to these resources—it involved electricians and hydraulic engineers who helped the communities to reconnect to electricity and water supplies. And on this basis, they began broader collaborations.

I met women who established an orange grove on land irrigated with reclaimed water. In an extremely poor town with 80% unemployment, these women were able to cultivate their fields and produce vegetables. They rejected racial and class segregation. They developed recycling commons, food commons, cooperative nurseries and so on. Their well-being improved. Conclusion? Start from where you are, pool in the resources, engage different skills, make decisions strategically to empower your case further and move forward.

The fundamental question is how do we reclaim the resources and change the system from below.

The fundamental question is how do we reclaim the resources and change the system from below.

My travels to the Andes in 2010 coincided with the tenth anniversary of Cochabamba Water War in Bolivia. Similar scenario: the government attempted to privatise the water supply infrastructure and was planning to outsource its management to multinationals, who were about to install meters in the poorer districts. The pipes in those areas were constructed by the residents themselves since they did not have access to the public water system—that is the commons. The people organised water associations by neighbourhoods and then established a joint association as a political response to the state. So the private companies’ intentions to put meters on the pipes and wells and ban collection of rainwater sparked a big movement.

After four months of protests, the movement was able to force the government to make a U-turn on privatisation policies. This led to the constitutional change recognising communal economy and to electing the first indigenous president in South America—Evo Morales. A few years later, however, he began another phase of enclosures and extractivism of raw materials in the name of economic growth due to political pressure.

We need to devise strategies for sustaining the efforts of the commons. And this can be achieved by organising more commons: a radically democratic alternative to state- or market-administered societies and a platform for building a movement for broader cooperation.

Until a few years ago, I heard about commons mostly in relation to the ‘tragedy of the commons’, according to which, in a shared resource system, individuals would act selfishly in the name of their self-interest. Thus, their behaviour would be contrary to the common good of all users. How does the concept of commons respond to the ‘tragedy of the commons’?

‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ was the title of the paper by Garrett Hardin, published in 1968 in Science. He explored a hypothetical scenario: a field is used by several herdsmen and, obviously, each of them seeks to maximise the number of herd grazing in the pasture. After a while, the piece of land is depleted.

Free access to resources must necessarily co-exist with a commons; otherwise, a space that is used by individuals with no relation to each other and no responsibility towards it would depleted.

But Elinor Ostrom pointed out that such a scenario does not meet the criteria of commons. It lacks the community setting the norms of access, taking decisions in a participatory way and having an awareness of environmental sustainability.‘The tragedy of the commons’ is, in fact, about the detriment of free access outside the commons. Free access to resources must necessarily co-exist with a commons; otherwise, a space—be it land, river, lake or sea—that is used by individuals with no relation to each other and no responsibility towards it would depleted.

Can commons thrive in the conditions of the global market?

No, the commons cannot thrive in the global market. But neither you or I can thrive in these conditions.

The commons could help us transform our social practices and our relationship with the biosphere towards prioritising dignity over profit.

Do we need to list all major crises around the globe caused by the activity of global markets? The commons, however, could be a means of breaking away from the reign of such a system. The commons could help us transform our social practices and our relationship with the biosphere towards prioritising dignity over profit, living meaningfully over living fast, and being in sync with the environment rather than balancing the books of multinational corporations.

You are currently living in London. What is the progress of commons there? Are there any sprouts of such social systems?

London is a global financial centre. Its framework, therefore, is the opposite of commons. Expropriating of common resources is happening on many levels there—from installation of benches that preclude homeless people from staying on them to criminalisation of squatting in many empty properties. There are, however, many commons developing on the fringes of the metropolis: community centres, land allotments, community gardens and housing cooperatives, just to name a few.

Small scale farmers of Campi Aperti in Bologna came together and established a completely different type of market.

I believe that London can learn from other European cities. A particularly motivating example is the experience of Campi Aperti in Bologna: small scale farmers—who otherwise would have been threatened by the capitalist markets—came together and established a completely different type of market which is embedded within the commons. The Bologna association, which the markets are part of, decides on the prices and the quality of produce.

Campi Aperti. Photograph by Michele Lapini.

Campi Aperti. Photograph by Michele Lapini.In most cases, small scale farmers become completely dependent on the global markets and large distributors who buy their produce at a very low price and resell it to supermarkets at a higher price. In a more conventional setting, these farmers would have been marginalised and segregated. Vis-à-vis the global market, they would have been the small players, yet, through the commons they provide good organic produce and sell it at a low price, affordable to the residents of poor neighbourhoods. By doing so, they bring together social and environmental justice.