Above Photo: Looking at Goldcorp’s Los Filos mine in Guerrero, Mexico. Photo: Cristian Leyva/Miningwatch Canada

In more than two-thirds of the mining-related lawsuits against governments in the region, communities have been actively organizing against the mining activities.

The right of foreign investors to sue governments in international tribunals is one of the most extreme examples of excessive power granted to corporations through free trade agreements and investment treaties.

For decades now, corporations have used this power to demand massive compensation for public interest regulations and other government actions that may reduce the value of their investments. Widespread outrage over this “investor-state dispute settlement” system is among the key issues in the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

But this public outrage hasn’t stopped companies from continuing to file such lawsuits. In January 2019, for example, U.S.-based Legacy Vulcan LLC registered a case against Mexico over an environmental dispute concerning limestone quarrying near the well-known vacation destination Playa de Carmen. The company cited ecological land use regulations in the municipality of Solidaridad preventing the company from expanding mining operations on two properties. Using NAFTA investment rules, the company is reportedly planning to demand approximately $500 million in compensation.

The same month, U.S. firm Odyssey Marine Exploration filed its notice of intent to sue Mexico for the outrageous sum of $3.54 billion for having failed to obtain permits needed to advance an offshore phosphate mine project off the coast of Baja California Sur. This is the largest amount that Mexico has ever been threatened within any ISDS suit.

These are just two of 38 mining-related investor-state cases documented in a new report by the Institute for Policy Studies, MiningWatch Canada, and the Center for International Environmental Law. Extraction Casino: Mining Companies Gambling with Latin American Lives and Sovereignty through Supranational Arbitrationexposes how transnational mining companies are among the biggest abusers of this system — especially in cases of unwanted investments where communities are in hard-fought battles to defend their land, water, health, and ways of life from the destructive impacts of mining.

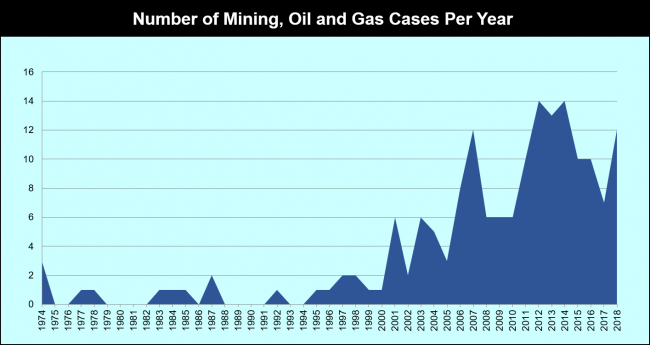

Worldwide, the extractive sector is behind 24 percent of all known investor-state claims and the number of mining-related cases is booming. Out of the 169 cases filed by oil, gas and mining companies since 1974, 96 have been filed since 2010.

The geographic distribution of mining-related cases is concentrated in Latin America, where Central and South American governments face 29 percent of known claims. This report looked at all 38 of the mining-related cases that have been brought against Latin American governments with increasing intensity since 1998.

Canadian firms have brought most of these cases, reflective of the disproportionate role of Canadian financing in the global mining sector. Some 55 percent of Canadian mining assets abroad are concentrated in Latin America.

Some of the hardest hit countries include Colombia, which currently faces over $18 billion dollars in threatened or pending suits. Just one of these suits claims $16.5 billion. These claims relate to government actions aimed at protecting Indigenous territory and fragile páramo ecosystems, which provide water to over a million people.

Mexico and Uruguay face over $3 billion each in suits for measures that have put ecologically-sensitive areas off-limits to industrial mining. Guatemala and Ecuador are also facing suits or threats of suits related to gold and silver projects that communities have spent many years fighting, facing criminalization and threats to defend their water, health, and livelihoods.

GLOBAL INEQUALITY

get the facts

Notably, the majority of these cases have been brought by exploration companies that have no operating mine, or no other mining project at all, and are making a last-ditch effort to extract millions or even billions of dollars from governments in the region through international arbitration whether they have followed local environmental and mining regulations or not, and almost always lacking community consent to operate.

While corporations and governments are exclusive parties to ISDS suits, we find that companies are often targeting laws, court decisions, and other measures resulting from the difficult struggles of mining-affected communities. In over two-thirds of the 38 cases examined, communities have been actively organizing to resist mining activities and defend their land, health, environment, self-determination and ways of life. As a result, these investor lawsuits represent a further assault against their self-determination and already limited legal protections.

In terms of the nature of government measures in dispute:

- In one-third of the cases, corporations are retaliating against measures related to Indigenous Rights and community consent;

- Over half of cases concern the enforcement of environmental and health protections; and

- Over one-third concern resource management (including nationalization or taxation).

For transnational mining companies, the power to bring suits to supranational arbitration is yet another opportunity to strike it rich through reckless, casino-style gambling. In this system, the deck is heavily stacked in their favor. The corporations are allowed to bypass domestic courts and sue governments before private tribunals, such as the World Bank-affiliated International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. The tribunal members are highly paid corporate lawyers who have no obligation to consider the rights of local communities or the importance of health and environmental protections.

Current investment rules are a threat to public and environmental welfare, as well as the right to community self-determination and national sovereignty over policymaking. Investor-state dispute settlement should be abolished, and all trade and investment treaties should be audited and, only after meaningful public participation, either be cancelled or rewritten in terms that put people’s rights and the environment first.