Above Photo: From Jacobinmag.com

At the start of the coronavirus epidemic, Norway’s government said it would help businesses by making it easier for them to get rid of workers. But trade unions and left-wing parties fiercely denied that these measures were “inevitable” — and they won a bailout to serve working people, not just their employers.

Like most of Europe, Norway has been hit hard by the coronavirus epidemic. After several weeks of dragging its feet, on March 13, the government moved into action, following its neighbor Denmark in closing schools, kindergartens, and then the border. It made a list of those exercising “critical functions in society,” like nurses, transit workers, cleaners, and people working in grocery stores, who can still work and have daycare for their kids. The rest of the public sector has been sent home — and private-sector firms are strongly encouraged to follow suit.

Faced with this situation, many Norwegians withdrew to their cabins — either to enjoy an extra holiday or because they thought this was a smart place to isolate themselves. But these cabins are often located in small municipalities with limited resources — and local mayors started asking for troops to help chase out the new arrivals. Faced with this new kind of “cabin fever,” on March 15, the government wrote a new law to ban such trips, on pain of a €1,300 fine.

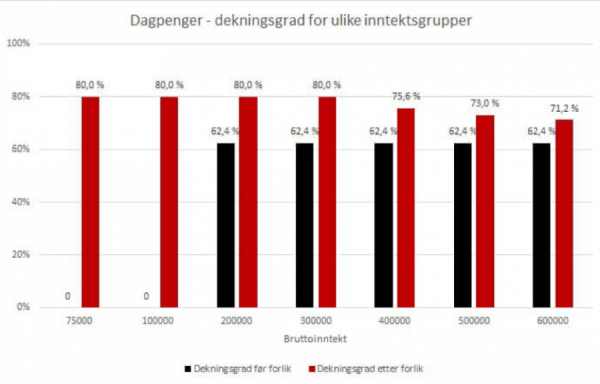

Yet the controversy also spread far wider — to the question of who will pay for the crisis as a whole. On March 10, the ruling right-wing coalition proposed a series of measures that focused on helping businesses suffering from the lockdown. This promised to make it easier, quicker, and cheaper for bosses to put employees “on leave” — without shifts. Normally a business can force staff onto leave because of seasonal work patterns — but would then need to pay them fifteen days’ full pay, after which social security would pay them 62.4 percent of their previous income. The government proposals would have slashed this full-pay period from fifteen days to two, after which a person on €2,500 a month (a low salary in Norway) would be left with just over €1,500.

But these plans didn’t come to pass. For the right-wing coalition is a minority government, and the parties of the Left, trade unions, and people all over Norway protested. “This is just a gift to the wealthy,” complained the economic spokesperson of the Socialist Left party (SV), Kari Elisabeth Kaski. The leader of the socialist party Rødt, Bjørnar Moxnes, accused the government of sending the bill to the workers, while the leader of the trade union confederation LO, Hans-Christian Gabrielsen, called the proposal unfair and unacceptable.

Sadly, the Left is used to making this kind of complaint from opposition — without being listened to. But this time, things were different. The government had sought to help business owners and banks with tax cuts and easier procedures for putting workers on leave — appealing for “national unity” as it insisted that the crisis made all these measures necessary. But this time it didn’t fly. And today, the Left is managing to secure emergency measures that deal with the social effects of coronavirus.

Split Government

This turnaround is partly owed to the weakness of the government itself. Consisting of three right-wing parties, it has been a minority coalition since the fall, when the far-right Progress Party (FRP) and its ministers left amid much fanfare in a dispute over Norwegian citizens connected to ISIS returning from a refugee camp in Syria. In truth, FRP’s real motive was likely its desire to be in opposition before next year’s general election, as the party has lost a lot of voters while presiding over unpopular spending cuts and centralization. This, combined with the left-wing parties’ strengthened polling position — also pushing the center-left Labor Party to take clearer stances — allowed the opposition to call the government’s bluff in parliament on Friday.

But what helped ensure the government’s defeat was the power of Norway’s trade union movement — and its democratic organizing structures. For it soon became apparent that union members would not stand for losing large chunks of their income while banks and bosses were being bailed out by the government. Branch leaders of the LO union recognized the mood, understanding they’d need to fiercely oppose the government proposals if they were to have a chance of getting reelected at the next union congress.

This left the LO and the Labor Party no choice but to go hard against the right-wing coalition’s plan. The government had to decide whether to seek a full-blown class conflict — a battle that they would surely lose in the court of public opinion — or to concede to union demands. It might sound reasonable enough for us all to act in “unity” at a moment of crisis. Yet in this case, the parties of the Left did not hold back in insisting that these attacks on workers’ rights were neither necessary nor inevitable — and the government was forced to back down.

This led to hasty discussions among all nine parties in parliament throughout the weekend, and on Monday morning, a new and much more social set of measures was presented. Decisively, this means the state taking a more proactive role. Workers put on leave will now get full pay for twenty days (an improvement even on the pre-coronavirus situation), but employers will only cover the first two days, while the rest will be paid by the state. After that period, a worker on leave will receive 80 percent of their previous salary, up to €26,000 a year, and 62.4 percent of everything they received on top of that.

In other words, while any worker would be worried to be sent home indefinitely, they will suffer much less than the government initially proposed, or even than they would have expected before this crisis. The right to receive such payments has also been granted to lower earners than previously and is now extended to everyone earning more than €6,500 per year. That’s very important for people working part time and on bad contracts, as they are included in social security for the first time. These measures are temporary and made for those on leave, not people who are laid off entirely or the already unemployed. But Rødt and the Labour Party have demanded that this be changed before the bill officially gets passed on Thursday — making these rights equal for everyone.

A Coordinated Response

Of course, workers have problems other than being told not to show up anymore. So-called care days — days you are allowed to stay home with full pay to take care of others, in most cases sick children — have been doubled from ten to twenty. The measures also extend to those with a weak connection to Norway’s highly organized labor market. Freelancers, people running their own business, culture workers, and others who see all their assignments vanish in a day will now get social security help, amounting to 80 percent of the average of what they earned over the last three years — up to a limit of around €52,000. The payout starts on the seventeenth day after they stopped having an income.

These measures have been mostly well accepted, and all parties are now boasting of their unity — despite the wound clearly inflicted on the government. But many things remain unclear, from the conditions of the aid for freelancers (e.g., whether you allowed to work at all if you receive benefits), to further-reaching ideological battles — for instance, the conditions imposed on businesses and banks who receive bailouts. The left-wing parties are pushing hard for a ban on dividend payments to the shareholders of businesses and banks that receive state aid, while the Right refuse such a measure, insisting that capital can “self-regulate.” The Labor Party has joined the left-wing parties in their demand for a ban, a clear sign they have been pulled to the left. Even a few years ago, they would probably also have claimed that the market can regulate profits and bonuses without intervention.

The last few days in Norway thus point to promising signs for the Left. First, it has shown itself strong enough to vote down the government’s crisis plan and enforce a much better one. Second, we have seen that welfarist policies — in this case, bailing out the people, not just businesses — are so popular that even the far right feels the need to go along with them, so as not to completely lose their brand as being “for the people.”

It’s natural that people wonder how they will pay their bills when they are put on leave, and that those who’ve lost their incomes overnight will demand help. As the leader of the center-left Farmers’ Party (Senterpartiet), Trygve Slagsvold Vedum, said, this package is “very expensive, but the alternative is even more expensive.” With strong left institutions, like a trade union confederation with more than 950,000 members in a country with 5 million people, this common sense has a lot of power behind its demands.

Measures taken thus far are mostly there to help people placed “on leave” — so far, there’s been less discussion of outright layoffs. Businesses seem to prefer to put their workers on hold, waiting to see how things play out. Yet layoffs will come, and the trade unions are already preparing for an offensive similar to what happened after the financial crisis, when full-time employees were laid off and then replaced with part-time and temporary work.

A lot remains to be done — and the right wing is still in power. But this weekend showed how, even in a time of crisis, measures to raise conditions for everyone while also defending the most vulnerable could assert themselves as “common sense.”