Above photo: First responders from IU Health Bloomington Hospital pick up a person describing COVID-19 symptoms in Bloomington, Indiana, March 23, 2020. Jeremy Hogan/Echoes Wire/Barcroft Media via Getty Images.

A couple of weeks ago, as countries scrambled to protect their citizens from the COVID-19 pandemic by closing borders and quarantining travelers, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, upon the “recommendation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” took the unprecedented step of urging all students who are studying abroad to return home. In the announcement, they emphasized the need to return home if students are living in a country with “poorly developed health services and infrastructure … for example the USA.” The word spread quickly on social media that the United States had been singled out as an example of a country with poor health care infrastructure, with many people in the U.S. agreeing that we lack the capacity to handle the pandemic.

There are many reasons why the United States, which spends the most per capita on health care each year of any wealthy nation, is lagging behind other countries in health care access. Compared to other wealthy nations, the United States stands out for lacking a universal health care system and for prioritizing corporate profits over health. This has led to a fragmented health care system that is ill-equipped for a coordinated response in a time of crisis, such as the current pandemic.

If there is any question that profits matter more than health in the United States, here are three recent examples.

Health insurance companies pushed back when President Trump announced treatment for COVID-19 would be covered without requiring co-pays. America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry lobbying group, immediately clarified this would only apply to testing, not to treatment. Rising Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures the antimalarial drug Chloroquine that is being tested for use against COVID-19, raised the price of the drug by nearly 100 percent in late January. Incidentally, this drug is still experimental and should not be used without medical supervision, as this Arizona couple did to their demise. And rather than purchase COVID-19 tests from the World Health Organization, as South Korea did, the United States chose to develop its own tests. This has led to a severe delay in access to tests, which means the U.S. missed an important window of opportunity to identify and isolate people infected with COVID-19.

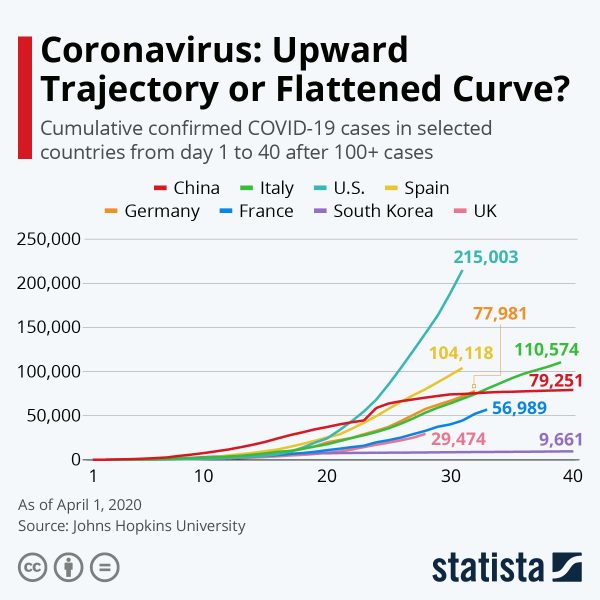

Now, the United States finds itself in the dangerous position of facing a potentially massive number of cases of COVID-19, as Italy is currently experiencing, that could overwhelm our health care system. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated earlier this month that between 160 million to 214 million people in the U.S. could be infected over the next year or so if nothing were done to stop the spread of the virus. Although steps are increasingly being taken, such as closing schools, banning large gatherings and shutting down nonessential businesses, the current rise of cases in the U.S. is steeper than in countries that are experiencing significant difficulties, such as France, Germany, Spain and Italy.

You will find more infographics at Statista

Not Enough Hospital Beds

According to the Global Health Security Index, the United States ranks 175th out of 195 countries for access to health care. Italy ranks 74th and it is having problems with overcrowded hospitals and being forced to prioritize patients for intensive care based on their likelihood of surviving.

Since 1975, while the U.S. population has risen from 216 million people to 331 million, the total number of hospital beds has declined from 1.5 million to 925,000. This decline followed President Nixon’s 1973 Health Maintenance Organization Act, which allowed the privatization of health care. The United States currently has only 2.8 hospital beds per 1,000 residents, just a little over half the average of 5.4 beds per 1,000 residents in other wealthy countries.

According to the American Hospital Association, there are nearly 70,000 intensive care unit beds for adults. This won’t be nearly enough to care for the estimated 2 million people who could be hospitalized for COVID-19. Most intensive care units are near full capacity on any given day. On March 27, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo stated that New York City will need an additional 87,000 hospital beds including 37,000 more intensive care unit beds on top of the 3,000 that currently exist.

New York City has been inundated with cases of COVID-19. As of this writing, there are nearly 50,000 cases in New York, most of them in and around the city, making it the 6th highest place in the world. Doctors and nurses report confusion over policies regarding the pandemic and shortages of critical supplies such as personal protective equipment, tests and medical devices, including ventilators. The governor reached out to President Trump to ask the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build temporary health care facilities, and so far, they have repurposed four buildings to create 4,000 beds and are looking at four more facilities plus using college dormitories and hotels as temporary hospitals. A 750-bed naval hospital ship just docked in Manhattan, in preparation for mid-April when they expect the number of cases to peak.

Where Did the Hospital Beds Go?

Hospitals are closing in the United States at an alarming rate. In 2018, an audit of hospitals by Morgan Stanley found that 8 percent of them are at risk of closing and an additional 10 percent are on a weak financial footing. In 2018, the American Hospital Association estimated that 30 hospitals will close each year and the number is expected to rise over time.

Rural hospitals are closing the fastest. Over 120 have closed down since 2010. A report by the Chartis Center for Rural Health found another 453 of the 1,844 that remain are at risk of closing. The highest number of rural hospital closures, 19, occurred in 2019. Six rural hospitals have already been shut down this year.

Roughly 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in a rural area. Residents of rural areas tend to be older, sicker and poorer than in other areas. They require more care and often can’t pay for it, placing a greater financial burden on local hospitals than populations that are healthier and wealthier. Hospitals are also facing competition from outpatient surgical centers, which draw insured patients away who can pay for care, thus lowering hospital revenue further.

When hospitals are located in communities with high numbers of uninsured residents, they are particularly vulnerable to closures. According to the University of North Carolina’s Rural Health Research Program, the 17 states that did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act had the highest number of hospital closures. Texas lost the most hospitals, followed by Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and North Carolina. Over half of the remaining rural hospitals in Texas and Tennessee and more than a third of hospitals in Oklahoma and Georgia are at risk of closing due to their weak financial position.

Failing rural hospitals are preyed upon by large corporations that take them over, extract their revenues and then allow them to lapse into bankruptcy. Kaiser Health News describes one case of a Miami, Florida-based corporation, EmpowerHMS, that bought 18 hospitals in the South and Midwest. EmpowerHMS ran a lucrative but fraudulent laboratory operation out of the hospitals, bringing in tens of millions of dollars, while the hospitals themselves lacked basic supplies and equipment. In the end, 12 of the hospitals went bankrupt and eight closed. Towns were not only devastated by the loss of their local hospital and the jobs that went with it, but they were also cheated out of hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid property taxes.

When hospitals close down in rural areas, more people die of preventable causes. In general, the Pew Research Center found people living in rural areas travel twice as far as people living in urban and suburban areas to get to the hospital. According to a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, mortality rates rise by 5.9 percent when hospitals disappear, especially for people with emergencies such as strokes and heart attacks that require immediate attention.

Hospital closures in cities also tend to occur in areas that serve poor communities and often populations of color. Like rural hospitals, they may be bought by a large corporate hospital system when they are failing and then allowed to go bankrupt. It is often more profitable to redevelop them in a gentrifying area than to keep them open.

This is what happened last September to Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia, which served a predominantly Black and Brown community for 178 years and is now slated for redevelopment. Providence Hospital in Washington, D.C., St. Vincent’s Hospital in the Greenwich Village area of New York City and St. Vincent Medical Center in the Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles, which also provided care for over a hundred years to low-income communities of color, have also been shuttered.

In other cities, hospitals may stay open but close down essential services to make way for more lucrative fields such as orthopedics and cardiovascular disease. MedStar, a Washington, D.C.-based corporation that owns 10 hospitals in Maryland as well as physician practices, laboratories, long-term care centers and other health facilities, abruptly closed whole departments that provided obstetric, pediatric and psychiatric care in recent years.

Profits Before Patients Is a Failed Model

As COVID-19 spreads around the world, now impacting over 700,000 people in 194 countries and territories, there is a clear difference in how well various countries are containing the pandemic. Those countries that have universal, publicly financed health care systems are better able to coordinate their responses and care for those who are ill. They have been the fastest to slow the spread of the virus.

For example, a World Health Organization mission reported that, “China has rolled out perhaps the most ambitious, agile and aggressive disease containment effort in history.” China was commended for the speed with which it identified the virus, acted and modified its strategy as new information was gained about the virus. Now, China is sending medical teams and supplies to other countries that are struggling.

Other countries with single-payer health care systems have also shown their superiority to the United States in handling the pandemic. Patients are able to receive care without concern about the cost and health facilities already have direct communication with the government in order to coordinate care.

The Washington Post quotes epidemiologist David Fisman of Toronto, Canada, who says, “having a healthcare system that’s a public strategic asset rather than a business run for profit allows for a degree of coordination and optimal use of resources.”

That is the reason the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is playing a fundamental role in the COVID-19 response in the United States. As the nation’s largest publicly owned health care system, the VHA has a “fourth mission” to assist in national emergencies. Candice Bernd of Truthout describes how the VHA is currently coordinating the emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic in cooperation with the CDC and the Department of Health and Human Services.

If the United States had a universal single-payer health care system like a national improved Medicare for All or a national health system modeled on the VHA, hospitals would not be closing down. A key feature of the House bill for Medicare for All is that it provides global budgets for all health facilities. They would receive a monthly check to cover the costs of providing care no matter what segment of the population they serve. (This provision is lacking in the Senate Medicare for All bill, and should be added.) The VHA owns its health facilities and similarly does not have to worry about turning a profit to keep the doors open.

Support for a universal single-payer health care system in the United States is growing. We can only hope that, in the face of this deadly pandemic, we will see a louder demand and the political will to finally join the rest of the world in treating health care as a public good.