Above photo: Chicago Teachers Union members and hundreds of supporters march through the Loop to call for the Chicago Board of Education to vote to end a $33 million contract between Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Police Department, Wednesday, June 24, 2020. Ashlee Rezin Garcia/Sun-Times.

Protesters demanded CPS oust cops from schools at demonstrations Wednesday downtown and outside the home of Board President Miguel del Valle.

Chicago’s school board has voted against ending a program that puts police officers in public schools, following the wishes of the mayor and top Chicago Public Schools leadership while rejecting the demands of students and activists who for years have called for police-free schools.

While the narrow 4-3 vote, the most suspenseful by the Board of Education in years, keeps intact a scrutinized $33-million contract between the school system and the Chicago Police Department, another vote is likely in the next two months on whether to renew the contract that’s set to expire at the end of August.

Ahead of the highly anticipated vote that for now leaves more than 200 officers in about 70 schools, students and activists held protests across the city, including in front of the board president’s house, to give one final push toward dumping the contract. The decision marks a defeat for activists who have protested in massive numbers against school police since the killing of George Floyd last month, and who hoped to see one of CPS’ most significant policy changes in recent memory in a rebuke of Chicago police.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot and CPS CEO Janice Jackson have fought against the blanket removal of school cops, saying it should be up to each individual school’s Local School Council made up of parents, teachers and community members. LSCs were given the power this past school year to decide whether police should remain in their schools and not a single one voted to get rid of its officers. LSC members around the city, however, complained about short notice before the vote and a lack of information on the issue. The councils are set to consider the issue again later this summer.

Board member: Wrong to spend CPS money on guns and Tasers

School board member Elizabeth Todd-Breland, who led the charge to end the police contract, argued a decision shouldn’t be in the hands of the LSCs because research is clear that the presence of officers hurts Black and Brown students.

“I’m a Black mother. I’m a resident of the South Side of Chicago. I’m a former LSC member. I’m a former high school college counselor and a historian and an education researcher who studies race and education in Chicago. And in all of these roles, I am clear that police do not belong in schools,” said Todd-Breland, an assistant professor of History at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“We use board money to pay for guns and Tasers in our schools,” she said. “This is not about individual officers, this is not about a relationship folks have had with an Officer Friendly. This is a deep, institutional and systemic problem that requires a systemic response and transformation. It is not enough to reform or make a better-trained or kinder school-to-prison pipeline.”

Todd-Breland was joined by the other two women on the board, Amy Rome and Luisiana Melendez, in voting to end the police contract. The board’s four men, including president Miguel del Valle, vice president Sendhil Revuluri and members Lucino Sotelo and Dwayne Truss, chose to keep officers in schools.

Melendez said she was saddened by the motion’s failure because there are “so many things in the police culture that need to change radically and quickly if we can all say with pride that their presence in our schools is gonna make our students better.

“Unfortunately, police departments in this country have proven to be racist,” Melendez said. “Not individually, but culturally. And that is what worries me. Will we be able to start enacting change to transform that, so that students in our schools, if they’re Black and Brown, don’t have to fear that they’re four times more likely to be the target of unfair police practices? I don’t have the answer to that.”

Truss: Cops create a sanctuary

Truss, a longtime activist on the West Side, said his and other Black communities have been “under siege by gun violence,” and that having officers in schools creates a sanctuary for students to get away from the trauma. “School resource officers are needed in the schools that want them,” he said.

Del Valle both said that growing up he was beaten by gang members at his school and nobody was around to help. Sotelo said police can have a negative presence, recalling he was harassed by both gangs and police when he was young, but he warned of “unintended consequences of doing this so abruptly,” saying students will drop out if they don’t have safety at school — which he believes officers provide.

Revuluri appeared to be the member most on the fence about the issue, asking questions of district officials even just moments before the vote. He pointed out that another vote will need to be taken in July or August, leaving open the possibility he could change his mind. But he said an alternative to school cops needs to be developed by then, and he wasn’t sure if that was possible.

“We are long overdue for reimagining what safety looks like in our schools. And we need to do that,” Revuluri said, adding that “we can’t just pass the buck of this decision to” LSCs.

CPS already employs almost 1,100 security guards who are stationed at schools including those that have police officers, according to district records. Those asking for police to be taken out of schools have said repeatedly officers don’t make Black and Brown students feel safe, and that they would rather the $33 million spent on policing to be used for social workers, counselors and nurses to address the trauma students face in communities hit hard by gun violence.

Aldermen weigh in

Several aldermen called into the online meeting to voice their opinions on the issue. In all, eight — Jeanette Taylor, Howard Brookins, Byron Sigcho-Lopez, Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez, Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, Andre Vasquez, Matt Martin and Maria Hadden — urged the board to end the police contract. Five of their City Council counterparts — Pat Dowell, David Moore, Derrick Curtis, Christopher Taliaferro and Nicholas Sposato — called to say they prefer officers remain in schools.

“Young people have told you from the very beginning, the young people that we claim to love … that police do not need to be in schools,” Taylor passionately argued. “Have any of you sitting on the CPS board … seen a student carried out of a school in handcuffs? In elementary school? My son has. And is that what we’re teaching them? How to put their hands behind their back?”

Sigcho-Lopez told the board that “unequivocally, this is a no-brainer” to remove police from schools. He pointed to the trauma faced by CPS student Dnigma Howard, who was 16 years old when she was shoved down a set of stairs and stunned with a Taser by Chicago police officers stationed in Marshall Metropolitan High School in a January 2019 incident that drew national headlines.

“A 16-year-old. I want to make sure you remember these words so you understand how this policy works and affects our youth,” Sigcho-Lopez said. “A police officer was screaming at the father of a special education child, a 16-year-old Black teenager, ‘Your daughter is going to jail.’ Now, is this the type of policy that we want to see in our schools?

“It’s immoral. It’s wrong. There’s no justification,” he said. “People are watching. People are seeing our decisions. This is the time for you to make a decision. Not to be a rubber stamp for the mayor.”

While the meeting went on, a march and rally was being held downtown to support removing police from schools. It featured Dnigma’s father, Laurentio Howard.

Dowell, one of the aldermen speaking in favor of police, urged the board to “take a measured approach” and “not to make a rash decision” by ending the police contract because the officers in her South Side ward have been a good presence in schools, she said. Other aldermen argued officers offer important protection for students from outside danger.

“I can’t imagine what it would be like without having a law enforcement officer there to protect our kids as well as our teachers,” Curtis said. “Our teachers are already overworked, and they shouldn’t be responsible for teaching and protecting at the same time.”

Students need to feel safe physically and mentally, CPS CEO says

Jackson said at Wednesday’s board meeting that it’s clear there are real concerns that have to be addressed about having cops in school, and students have to feel safe both physically and mentally. But she still wants each school to decide for itself.

“I don’t believe that a top-down mandate makes sense in this situation,” Jackson said. “If this were an easy issue and cut and dried we wouldn’t be spending so much time on it today. There are just a lot of people who have different views about it.”

Survey: Community wants cops out, students split

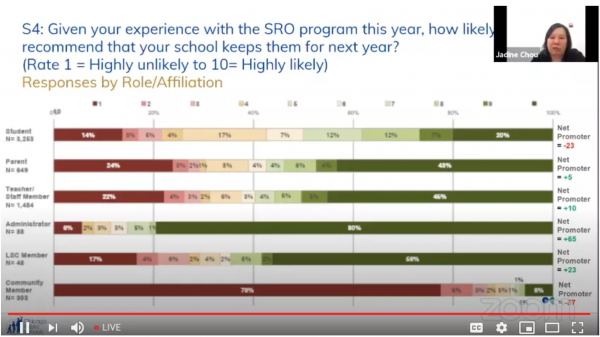

Jadine Chou, head of CPS’ Office of Safety & Security, told the board that a survey administered in May showed almost all community members — about 85% — strongly opposed keeping officers in schools, while 90% of administrators wanted police to stay.

About half of the 3,200 kids surveyed wanted cops removed, but their opinions were spread across the spectrum of the issue, according to CPS’ survey.

A combined 2,100 parents and teachers, meanwhile, had stronger feelings on both sides, with a little more than half of each supporting school cops.

It wasn’t clear where the survey participants live or with which schools they’re affiliated.

Chou added that the district has responded to concerns in recent years, acknowledging there wasn’t enough oversight on the program in the past. New rules for police in schools call for officers not to be involved in school disciplinary issues, allow principals to choose their officers and include stricter background requirements and training for officers to work in schools.

“We’re just asking for everyone to be on this journey with us,” Chou said. “We’ve come a long way as a district. We recognize we have a way to go. But we feel like we are making progress.”

Also speaking during the online meeting was Marvin Hunter, great-uncle of Laquan McDonald, the Chicago teenager gunned down with 16 bullets by former CPD Officer Jason Van Dyke,

“I hear very compelling arguments for both sides, but the truth of the matter is, speaking as a lifelong resident of the city of Chicago, the optics of having police officers in the schools is not a good look from the perspective of the community,” Hunter told the board. “Most people have been traumatized in our community at one level or another by uniformed police officers.”

As for his nephew’s murder, Hunter said “just that action alone proves that police … do not have the capacity to understand children, nor are they trained in that way.”

Another public participation speaker, Rebekah Fenton, a physician in Northwestern University’s Pediatrics Department, said she feels scared as a Black woman every time she comes across police officers, and that same fear is in Black and Brown students in schools every day.

“The school resource officer contract threatens the futures of Chicago’s youth,” Fenton said. “The mere presence of police in schools increases the risk of incarceration. Continuing this contract neglects and exacerbates the collective trauma of policing in Black and Brown communities both in and out of schools.”

Contributing: Manny Ramos.