Above photo: Tenant-Rights Rally in Seattle, Washington (2017). Backbone Campaign / Flickr.

Los Angeles is on the brink of one of the largest mass displacements in the history of the region. As eviction courts reopen, nearly half a million renter households, concentrated in Black and Latinx neighborhoods, are at risk of expulsion through unlawful detainers, or eviction filings—UD Day is here. In a deal struck with the landlord and banker lobbies, the California legislature has put forward tenant protections that postpone some evictions, keeping tenants in a state of permanent displaceability. In a cruel hoax, such protections convert unpaid rent into debt, turning the small-claims court into yet another arena of violence against working-class communities of color. Los Angeles is the paradigm, not the exception.

Writing from Los Angeles, I interpret the present conjuncture as emergency urbanism—the suturing of the ongoing “state of emergency” that is global racial capitalism with the declaration of emergency by the postcolonial state under the sign of public health. The most obvious manifestation of a public-health emergency is the COVID-19 pandemic and its racialized maps of infection and death that make visible the disposability of Black, Brown, and Indigenous life. But COVID-19 is conjoined with other takings of life. Patrisse Cullors, cofounder of Black Lives Matter, explains the state of emergency thus: “That black folks across the country and the globe are systematically targeted, and that our lives are on the line on a daily basis, and, that, ultimately, this is a life and death issue for us.”1

The state of emergency has always been here. In Los Angeles, as well as in other US cities, working-class communities of color are subject to what I call “racial banishment,” the enactment of their expulsion and disappearance from urban life.2 It would be a mistake to understand such processes as gentrification or eviction, in other words, as market-driven displacement, for they are part of the through line of the forced removals of people of color. Racial banishment is state-organized violence, instituted through regimes of racialized policing, such as gang injunctions, nuisance abatement, and place-based surveillance.3 Taking place in the name of the state’s police power to protect the “free use of property” and ensure the “comfortable enjoyment of life and property,” such forms of policing secure dispossession and enable formations of settler urbanism.

The Black Lives Matter uprising seeks to make such racialized policing and the dispossession of life untenable. Alongside such uprising in the streets, a reconfiguration of the social and spatial arrangements that make up urban life is also underway. In particular, property has become the insurgent ground of emergency urbanism, a site of rebellion against global racial capitalism and its protocols of rent and debt. The question at hand is whether such emergency presents the opportunity for a radical reconfiguration of the relationships among sovereignty, life, and property that are so central to American liberal democracy.

On May Day, amid the eerie quiet of the COVID-19 shutdown, activists with Street Watch LA, a tenant-rights coalition, staged the occupation of a suite at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. The key protagonist, Davon Brown, one of the nearly 70,000 unhoused Angelenos, had been until then living in a tent in Echo Park Lake, a public park that has been the site of fierce contestations over homeless encampments. Brown, who was portrayed in the national media as “Lady Gaga’s ex-model,” embodies the life-and-death emergency that is homelessness in America. With average life expectancy rates that rival the world’s so-called failed states—48 years for an unhoused woman and 51 years for an unhoused man—Angelenos experiencing homelessness are disproportionately Black, heavily policed, and subject to unrelenting criminalization by propertied interests, such as business-improvement districts. While cities such as Los Angeles imposed “safer-at-home” orders to protect life during the COVID-19 pandemic, the unhoused remain abandoned, excluded from state and social protection.

The Ritz-Carlton occupation, part of a state-wide No Vacancy! California campaign, drew attention to another dimension of emergency: the relationship between state power and private property. Fed up with the slow progress of Project Roomkey, a program that utilizes vacant hotel and motel rooms as emergency shelter for the unhoused, activists demanded the commandeering of hotels. They focused on “publicly subsidized” hotels, such as the Ritz-Carlton, that have benefited from tax rebates, land assembly, and many other such “geobribes,” Neil Smith’s felicitous phrase for the public subsidies provided by local governments to landed interest in order to facilitate urban development.4 Just in downtown Los Angeles, public subsidies to luxury-hotel development have amounted to $1 billion between 2005 and 2018. When housing-justice movements demand that hotels be seized to shelter the unhoused, they are seeking redress and reparation for such diversions of public money.

Commandeering is not only a political demand but also the vocabulary of legal reason. Early on in the COVID-19 shutdown, the law firm of Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP delivered a definitive legal argument stating that the mayor of Los Angeles had “broad authority” to commandeer property, including hotel rooms, “to protect public health in a declared emergency … without providing preseizure notice, an opportunity to be heard, or compensation,” as long as a “post-deprivation process” provided “just compensation.” A few days later, the city attorney of San Francisco arrived at a similar legal conclusion. While, to date, no government executive in California has deployed such authority, these legal statements linger as a haunting, gesturing at the possible interruption of established relationships between state power and property rights.

The emergency that is recognized in these legal declarations is not the takings of life under conditions of global racial capitalism. The relevant emergency is public health, which has long been a key domain for governments to manage class and race relations through the management of disease. The roots of modern urban planning lie in efforts to hold the line against the spread of diseases, such as cholera, through various forms of spatial segregation and social exclusion.5 While such practices were perfected in colonial settings where maintaining “the sanitary city” required containing and quarantining native populations,6 they persist in what I call the postcolonial state.7 Colonial logics of rule and subordination proliferate in and through the postcolonial state, vividly apparent in how disease is racialized and space is controlled.

Does the public-health emergency at hand interrupt or consolidate such logics? On September 1, 2020, as eviction courts reopened in states such as California, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), citing health risks, announced a nationwide moratorium on evictions, an order that supersedes local measures that “do not meet or exceed these minimum protections” and imposes criminal penalties on those violating the moratorium. While similar state-level eviction moratoria have faced legal challenges, the courts have repeatedly ruled that a halt on evictions does not violate the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment. If the CDC moratorium stands, it would mean that, for a moment, for this moment of emergency, the police power of the state would serve to protect human life rather than property. Well after the emergency is over, such an eviction ban could linger as a haunting. It could become insurgent ground.

Integral to the making of insurgent ground is a practice of space, what Saidiya Hartman calls “waywardness.” In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, one of the most important books of our time, she describes the long arc of Black freedom, foregrounding the lives of young Black women who “struggled to create autonomous and beautiful lives” through “open rebellion.”8 Along similar lines, Salwa Ismail argues that behind the spectacular occupations of plazas and squares of the Arab Spring was the prolonged emergency wrought by impoverished livelihoods, precarious housing, and intensifying policing. These oppressions and grievances took shape in the informal neighborhoods of cities such as Cairo, “in the microprocesses of everyday life,” creating “oppositional subjectivities” and “infrastructures of protest.”9

Such also has been the making of insurgent ground in Los Angeles. Take, for example, the People’s City Council LA and People’s Budget LA, emergent structures of popular sovereignty that demand the defunding of police and “a budget centered on humanity.” Coalitions of racial justice and housing-justice movements are rooted in long-standing struggles over redevelopment, gentrification, and policing, and now stand as a powerful challenge to the governing of/through crisis.

Yet another beautiful experiment is the popular appropriation of eminent domain, or the police power of the state to expropriate private property for public purpose. In El Sereno, the group Reclaiming Our Homes has occupied vacant houses that were acquired through eminent domain by Caltrans, California’s transportation agency, for a freeway that was never built. The COVID-19 pandemic led the editorial board of the Los Angeles Times to argue for such use of property: “The state cannot allow its own vacant houses or other public properties to sit unused and crumbling in a housing and public health emergency.” The editorial board went on to state: “Are the ‘reclaimers’ breaking the law? Of course. They’re trespassing on state-owned land and, essentially, claiming public property as their own.”

Housing-justice movements refuse such frames of illegal occupation. They instead ask, “What is this state-owned/stolen land on which unhoused people are trespassers? What is the law of the postcolonial state that upholds the rights of settlement and enforces the rightlessness of the dispossessed?” Organized theft has been legitimized through the protocols of market rationality, masking the forced removals of people of color as the improvement of property value in gentrifying neighborhoods. Unrecognizable dispossession is the prolonged state of emergency that is racial capitalism.

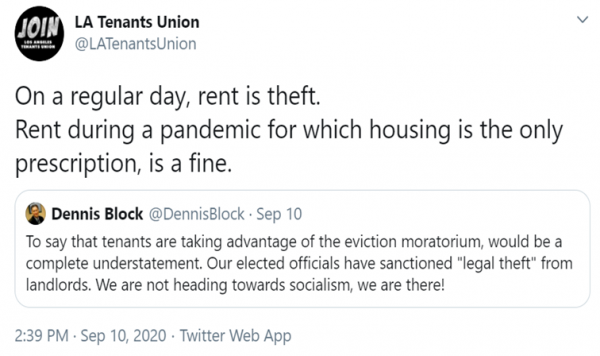

If property is the insurgent ground of emergency urbanism, then such insurgency is, perhaps, most evident in the political demand of rent cancellation. Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal, organizer with the Los Angeles Tenants Union, notes that most rent-relief funds are “pass-throughs for money that ends up in landlords’ pockets” rather than entitlements. By contrast, rent cancellation “would rewrite the script of power relations.” A rent strike, then, is more than the withholding of payment. It is a political demand for the protection of human life over the protection of property.

While Dennis Block, LA’s infamous eviction attorney, argues that a moratorium on evictions constitutes “legal theft” from landlords, sanctioned by state power, the LA Tenants Union responds that rent itself is theft. They invoke the dire emergency of life and death for which housing is “the only prescription.” Such are the capacious imaginations of emergency urbanism. In the strange articulations of crisis and uprising, an open rebellion is taking place against the meaning of property as it has been established in the afterlife of colonialism and slavery.

Crisis Cities is a public symposium on the 2020 crises and their impact on urban life, co-organized by Public Books and the NYU Cities Collaborative. Read series editor Thomas Sugrue’s introduction, “Preexisting Conditions,” here.

Notes:

- Jamil Smith, “Black Lives Matter Co-Founder: ‘We are in a State of Emergency,’” New Republic, July 20, 2015.

- Ananya Roy, “Dis/possessive Collectivism: Property and Personhood at City’s End,” Geoforum, vol. 80 (2017).

- Ananya Roy, Terra Graziani, and Pamela Stephens, “Unhousing the Poor: Interlocking Regimes of Racialized Policing,” White Paper for the Square One Project, Columbia University, 2020.

- Neil Smith, “New Globalism, New Urbanism: Gentrification as Global Urban Strategy,” Antipode, vol. 34, no. 3 (2002).

- As scholars like Paul Rabinow and Susan Craddock have shown in their works: Susan Craddock, City of Plagues: Disease, Poverty, and Deviance in San Francisco (University of Minnesota Press, 2000); and Paul Rabinow, French Modern: Norms and Forms of the Social Environment (University of Chicago Press, 1989).

- Colin McFarlane, “Governing the Contaminated City: Infrastructure and Sanitation in Colonial and Post-colonial Bombay,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 32, no. 2.

- In keeping with Saidiya Hartman’s work on the “afterlife of slavery,” I intend the postcolonial as the afterlife of colonialism, rather than after-colonialism. Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007).

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (Norton, 2019).

- Salwa Ismail, “Urban Subalterns in the Arab Revolutions: Cairo and Damascus in Comparative Perspective,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 55, no. 4 (2013).