Above Photo: Brisbane Tool Library volunteer, Jorge, introducing the project to a visitor. Sabrina Chakori.

How the Brisbane Tool Library provides an inspiring example of degrowth in action.

Based on principles and practices of resource use reduction, sharing, conviviality, solidarity, and mutual aid, the Brisbane Tool Library can be considered a small-scale laboratory for a reorientation of society towards degrowth.

Most of us are familiar with the social and environmental impacts of life under the Capitalocene (‘the age of capital’ — the historical era shaped by the endless accumulation of capital): inequality, commodification, imperialism, racism, and much more are already causing intragenerational suffering and ecological collapse. We are bombarded weekly with publications that assess the dire state of the world — and while I don’t want to focus on this, a brief reminder is in order.

There is extensive literature portraying the social and ecological degradation of our times (e.g. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, Stockholm Institute planet boundaries studies). Each Earth Overshoot Day is another reminder of the unsustainability of our current socio-economic model. Although the science has been clear about the unsustainability of our socio-economic system since at least the 1970s, the growth-driven system continues to exploit nature and labor across the world. For example, in order to fuel capitalism (grow and accumulate profit), techniques such as planned obsolescence — a mechanism used by producers to decrease the durability of their products and create the ‘need’ to replace them more frequently — have become widespread. The purpose of this article is to elicit hope and provide alternative imaginaries and practices — despite the constraints of the growth-driven capitalist system.

There is a growing literature on degrowth, defined — by Samuel Alexander — as a planned contraction of the energy and resource demands of overgrown economies as a path toward social justice, ecological viability and for human flourishing beyond consumerism and productivism. Now, these are fine words, but I would like to invite you to journey into how degrowth concepts can be seen in practice and they can inform our thinking about how degrowth might look in the real world.

I share here few key insights of my experience in being part of and contributing to the Brisbane Tool Library (BTL). Based on principles and practices of resource use reduction, sharing, conviviality, solidarity, and mutual aid, the BTL can be considered a small-scale laboratory for a reorientation of society towards degrowth. The most common understanding of a tool library is that it is a library for things, in which people can borrow tools, camping gear, kitchen appliances, and many other items. The work undertaken at the BTL since 2017, however, goes beyond lending items — it seeks to build systemic change.

The work of the Brisbane Tool Library aims to contract production and consumption of household goods, while recreating a strong and resilient community. First of all, tool libraries decrease material consumption (such as the use of virgin resources) by expanding and maximizing the use phase of various items. By stimulating a high-quality reuse, the tool library promotes a community-driven circular model in which resources are shared. At BTL, we point out that the growth-driven system is the root of the issues we seek to address. It is fundamental to re-politicize ‘waste’ and material exchange, and resist greenwashing ‘circular economy’ and ‘eco-businesses’ practices that, in order to expand growth even further, fetishize and commodify waste to relaunch growth.

By conceptualizing waste critically “as the inherent by-product of a regime that thrives on the excessive exploitation of labour and the environment”, as Michelle Yates writes, we would then be able to open up imaginaries that could help transitioning towards a degrowth society.

Access Over Ownership

The Brisbane Tool Library challenges the system’s misconception that quality of life rests solely on individual ownership of more and more things. It shows that we can meet people’s needs by prioritizing access over individual ownership. This enables a cultural shift towards an economy of sufficiency that nurtures limitation of private ownership as a cultural journey of plenitude. Additionally, by prioritizing access over ownership, tool libraries could also represent a way to reduce inequalities, in particular in cities. The Brisbane Tool Library, like many other tool libraries across the world (such as the Toronto Tool Library in Canada, Seattle Tool Library in the USA, Glasgow Tool Library in the UK Scotland, and La Manivelle in Switzerland) is based on a membership model, meaning that people pay a small annual fee that allows them to borrow various items through the year. (As a not-for-profit, all our surplus revenue is fed directly back into the organization.) This model allows people to save money on items, because for the price of one power tool people can access hundreds, if not thousands, of items. By guaranteeing equal access to people from all socio-economic backgrounds, tool libraries enable more people to achieve the same experiences, whether it’s a camping trip or a home renovation.

The Commons

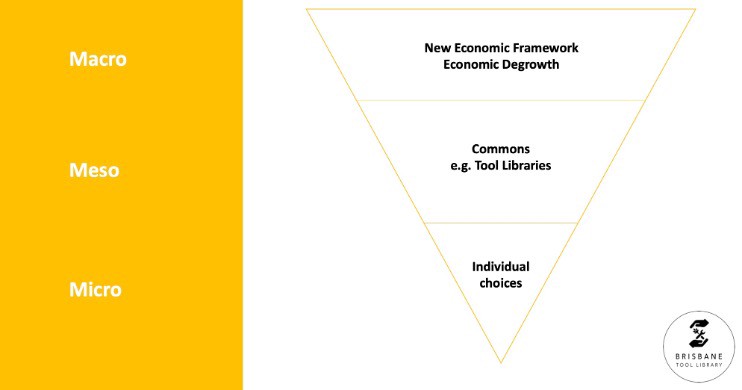

While top-down change is occurring in precisely the wrong direction — with a lack of socio-ecological positive action from governments (such as in Australia), and individualistic lifestyle choices (for example switching off the light and cycling) that remain constrained by the system — here, I would like to attract the attention to a third option that is often overlooked: the meso-level, in which commons can be recreated.

Another way to understand what we are doing at Brisbane Tool Library is creating a commons. The tool library is seen as a commons because it allocates common-use resources and, while this is true, it is not the things, per se, that are a commons. What makes a project a commons is not the object but the human relationships. People come together to find ways to meet their needs by sharing resources according to a set of agreed rules.

As mentioned, degrowth is about a planned contraction of the economic metabolism, hence it’s the conscious process and system of human relations directed at fulfilling a need that makes the object (tools, in the case of the BTL) a mechanism for creating a new set of social norms based on sharing. In a recently published book chapter, Shane Hopkinson and I outlined how commoning can challenge the growth-driven model by showing how different social relations embodied in sharing can overcome the alienation which is at the basis of the commodity production under capitalism. As Johannes Euler points out, a sharing economy based on the commons might be translatable in people being part of multiple commons-projects, shaping our cities to become sustained by complex and dynamics networks of commons.

Forms of conviviality and solidarity are required to maintain the commons and the affinity bonds on which is based. At the BTL, conviviality and solidarity take various forms — from personal help directed toward specific members and volunteers, to the sharing of group moments (e.g. birthdays, picnics, harder life moments) beyond the walls of the tool library. Activist lives are frequently characterised by a significant sacrifice of time, energy, and income. In the same way, the work of the Brisbane Tool Library requires a significant commitment from all the people involved. The commitment and participation of the members and volunteers shape a sense of collective practice. This co-operative behavior gives rise to a sense of identification, which then translates into mutual aid, reciprocity, collaboration, and inclusion.

The Brisbane Tool Library is far from a perfect organization or structure. It seeks to create a life in common and in negotiating the rules there is an active intention by the team to keep decision-making as horizontal as possible. Many of Brisbane Tool Library’s processes apply internally and our values (e.g. the condemnation of capitalist exploitation of labor and nature) align with traits of anarchist subcultures. For example, organization is always debatable, changeable, and can be constantly renegotiated. Although anarchist studies have been long marginalized in academia, anarchist organizations and activist groups continue to be a territory of exploration for new forms of social and political change.

The volunteers form a solid motivated team that has seen many members working towards this project for several years. People embark on work at the tool library knowing that no prior skills or experience are required and that every suggestion and opinion is welcome. New projects and suggestions are considered all the time, and the volunteers also meet at a monthly forum to discuss new propositions and updates. Propositions go beyond tools-related activities: Recently, for example, volunteers started a book club to explore and discuss literature on systemic change.

Finally, in developing the tool library, many constraints remain, such as the ability to access affordable or free spaces to operate from. Housing and rental markets, gentrification, and at its deepest private property, create bottlenecks to new social and ecological practices. The resistance and opposition to profit-driven sponsorships and tax-avoidance philanthropists’ donations, lack of basic income, and the general unfair competition of the capitalist system that externalizes social and ecological costs, make our work challenging.

However, in working towards systemic change, the Brisbane Tool Library can be considered a shadow network. Shadow networks are networks that operate outside the dominant system and function as incubators for new practices. While operating at the margins of the growth-driven system, we are constructing an alternative community-based project that points to paths beyond the growth-driven exploitation and circuits of production and exchange. By recreating the commons, we are demonstrating that a collective way of sharing, accessing, and using with changing ownership rights is not only possible, but desirable and needed.

Three Things You Can Do Right Now

- Find out more about the Brisbane Tool Library and, if you’re local, apply to become a member or volunteer.

- Help promote this article by sharing these posts on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. Sign up here for email alerts when articles like this are shared on social media.

- Find a tool library in your local area — or start your own!