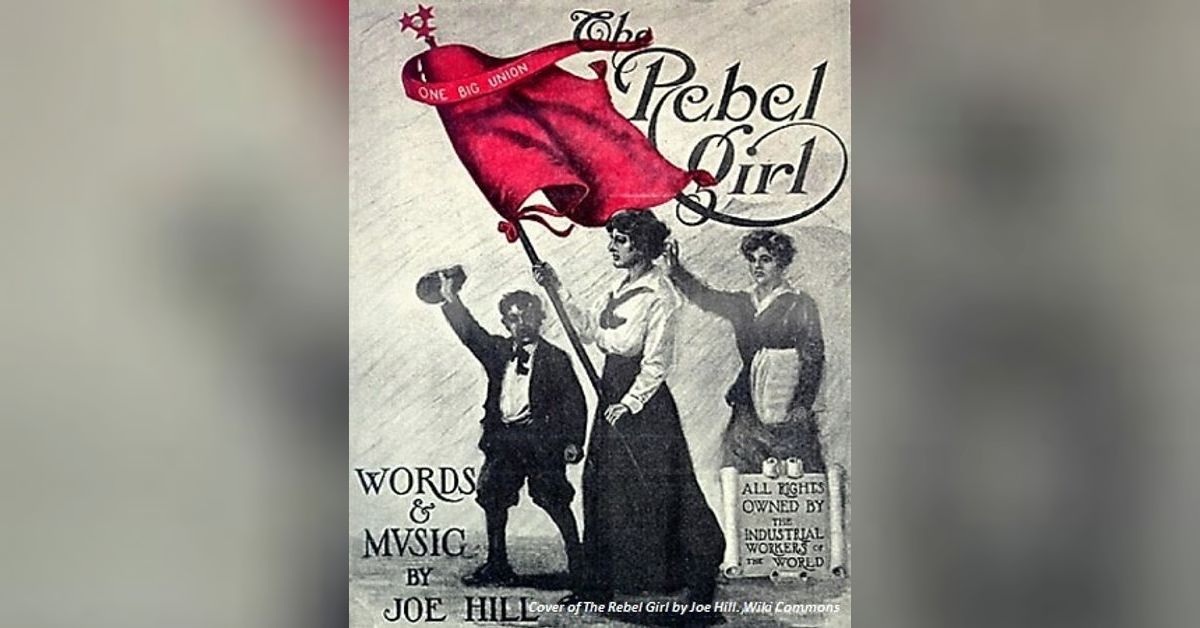

Above photo: The Rebel Girl. Library of Congress, Music Division. Open domain.

Peasants and Kings.

This is the second of three articles on how the American Left is remembered, or not, in the high school textbook, American History. Part II is focused on the roles played by the American Left in establishing the rights of labor.

Years ago, I took a sociology course in which we were taught how social class was determined by looking at a mix of family wealth, income, occupation and education. We were taught that those categories were often impacted by complex disparities in opportunity determined by race and gender.

Societies, we were taught, are stratified into class categories of upper, middle and lower, but those are often further divided into as many as six or seven groupings. At the time I could not imagine how these multiple divisions could be of much use. I still can’t.

It was not until I saw Monty Python and the Holy Grail, that those bewildering categories were cleared up. In one scene, King Arthur, dressed in white, interacts with two very busy peasants, a man and a woman, both dressed in mud. The apparently confused king asks the peasants who owns the castle on a nearby hill.

The peasants respond that they don’t know; no one lives there. A frustrated Arthur then loudly insists that he is their king and, besides, he is in a hurry. Both peasants continue their work, but the woman asserts that she didn’t know they had a king, mumbling, “I thought we were an autonomous collective.”

I finally realized that the most useful class division is the simplest: between those who are comfortable, including those who are, like the king, overly comfortable, and those who must struggle to survive.

I realized that the effort to establish the fundamental rights of labor, or of the working class, or of the peasants, is a struggle for justice: an effort to make the lives of those in the lower classes, whatever they are called, reasonably comfortable.

Recognizing the Rights of Labor

The answer to injustice is not to silence the critic but to end the injustice.

Paul Robeson

In what follows I will explore two questions: 1. How is the struggle for worker rights portrayed in high school textbooks? 2. What is written about the roles of socialists, communists and other parts of the American Left in recognizing worker rights?

In high school history textbooks, that struggle for justice is generally reduced to a policy debate in which labor’s demand for fundamental rights is reduced to demands for higher pay and shorter hours. Instead of emphasizing the rights of labor, the texts simply describe the abusive working conditions and the violence accompanying some strikes.

Little effort is put into assigning blame. The struggle of socialists, communists and fellow travelers to guarantee fundamental rights are at best marginalized, misrepresented or unnoted. If you want a more general background on how labor is portrayed in history textbooks I have written about that here and here.

Are Labor Unions Always Left-Wing?

There is a tendency, in textbooks, to imply that labor unions are anti-capitalist or left-wing. That is not true. Some unions, of course, have been anti-capitalist, but just as often the owners of capital have been anti-labor.

Strikes, often meant to recognize worker rights to a decent wage and safer conditions, are characterized in textbooks as “alarming many Americans.”

The American Federation of Labor (AFL)

The AFL, founded in 1886 as a collection of craft unions, organized skilled workers who were relatively privileged and mostly white and English speaking. For at least seven decades the AFL worked to reduce competition by excluding newcomers by advocating racist and anti-immigrant policies.

The AFL was never anti-capitalist. It never focused on social reform and was led by the so-called “pragmatic” Samuel Gompers. The 2025 AFL-CIO website (the two organizations merged in 1955) characterizes Gompers behavior as “unfortunate,” but admits that he “stood for white workers of his time, often pitting them against black and Chinese workers.”

Industrial unions on the other hand, like those in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) organized both skilled and unskilled workers and banned ethnic or racial discrimination. They advocated for social reform, organized immigrants and were often established and led by socialists and communists.

The conflict among workers and owners has never been even-handed. To this day, the American government has been overwhelmingly friendly to capital and largely unfriendly to unions. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, for example, established arduous limits on union power, that is the limits on the power of organized people while the Supreme Court, beginning in 1886, declared corporations persons and gave them rights such as due process.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

Work and pray, live on hay,

You’ll get pie in the sky when you die.From “The Preacher and the Slave” 1911

by Joe Hill (IWW activist and songwriter)

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was founded in 1905 in Chicago as a leftist labor organization by a number of industrial unionists including Eugene Debs. The IWW (called the Wobblies) was more than a union and thus able to do things eventually forbidden to unions like sympathy strikes. Nevertheless it played a vital role in a variety of union actions.

The IWW’s philosophy and tactics have been described as “revolutionary industrial unionism, with ties to socialist, syndicalist, and anarchist labor movements.”

In contrast to the AFL, the IWW sought to abolish the wage system and create a society where workers could own and control their factories. It emerged from the struggles of miners and railway workers, it aimed to unite all workers into one big union and it sought to challenge the capitalist structures upheld by organizations like the AFL.

The IWW and the Textbooks

In “The Americans,” there are vague references made to IWW “ties to radical groups,” but what that teaches students is a mystery. In a desperate attempt to seem informative without saying much, this text reports that the Communist Party “included members of the IWW,” but no attempt is made to explain why that might be important. Certainly, they can’t be suggesting that if a Wobbly joins the Communist Party, then the IWW is communist.

Then, without any evidence, the text reports that, “Communist talk … of government ownership of factories and railroads frightened the public.” But why government control of railroads and steel mills “frightened the public” is not made clear. It would be more instructive to write that, “Communist talk … of government ownership” frightened Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller.

In “History Alive!,” the closest the IWW comes to being identified accurately is when it vaguely suggests that the IWW introduced “radical ideas into the union movement” and reports that the IWW “believed socialism was the solution to working-class issues.”

There is no explanation of what those “radical ideas” were, rendering the statement educationally meaningless. The textbook habit of making vague references to “radical ideas” or “socialism” is inexcusable. What the IWW stood for was clear from the start. If publishers had wanted the students to understand the IWW they simply needed to quote the founding convention‘s first speaker and founding member Big Bill Haywood:

Fellow workers, this is the Continental Congress of the working-class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working-class movement that shall have for its purpose, the emancipation of the working class from the slave bondage of capitalism.

Working-Class Heroes: Eugene V. Debs and Victor Berger

A 22-year-old Eugene V. Debs had organized workers during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. He went on to found the American Railway Union (ARU) as an industrial union in 1893. And he led the ARU in the Pullman Strike in 1894.

After that strike, Debs was sentenced to six months in prison for defying a court injunction that essentially prohibited the strike. That allowed him time to read books on socialist theory and he emerged a committed socialist and soon became a founder, in 1901, of the Socialist Party of America.

Debs and his connection to the Socialist Party is in every high school history text I’ve seen simply because he is too important to ignore. Besides his role as the founder of the Socialist Party, he had been an elected member of the Indiana House of Representatives and the Socialist Party candidate for President of the United States 5 times, gaining more votes each time. If you are interested, I’ve written more on Debs here.

Victor Berger, along with Debs, was a founding member of the Socialist Party. He is not mentioned in any textbook I’ve seen. In 1910, he won the Congressional seat for Wisconsin’s 5th district and became the first Socialist in Congress. He lost that seat in 1912 and returned to being a newspaper editor and a Socialist Party leader.

Berger’s newspaper, The Milwaukee Leader, had its mailing permit revoked and was banned from using the United States mail because of Berger’s opposition to World War I. So much for freedom of the press.

Like Debs, Berger was indicted under the still-in-use Espionage Act for openly opposing World War I. Despite being under indictment, he was again elected to Congress in 1918, but when he arrived in Washington, Congress formed a special committee to determine whether he should be seated. The committee concluded that he should not and declared the seat vacant. Again, so much for freedom of speech.

On Feb.20, 1919, Representative Berger (although unseated) was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in federal prison (10 more than the sentence given to Debs). Nevertheless, on Dec. 19, 1919 the voters re-elected Berger and Congress again refused to seat him. In 1921 his Espionage conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court and he was then reelected to Congress in 1922, 1924 and 1926.

So, a major figure in the labor movement, a founder of the Socialist Party, the first Socialist elected to Congress and an opponent of WWI is not in the textbooks. What a surprise!

Working-Class Heroes: Labor Wars

The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) was one of the most successful early 20th century unions. It was formed on June 3, 1900 by eleven delegates representing local unions from the major garment centers in New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Newark.

Nearly 400,000 workers joined between 1909 and 1913. A majority of members were women, mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants, many of whom were socialists. Among them was Rose Schneiderman, a Polish-born American labor organizer, feminist and one of the most prominent female labor union leaders.

After the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, in which 146 garment workers were burned alive or died jumping from the ninth floor of a factory building, Schneiderman spoke to an audience of the Women’s Trade Union League which was made up of workers and their wealthier supporters. The 1911 speech is followed by part of a speech made in 1912.

This is not the first-time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 143 [3 died later] of us are burned to death.

What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.

Socialism Is Not What the Textbooks Says It Is

In the first part of this series of three articles, I mentioned the inadequacy of textbook definitions: they are vague and sometimes, inexplicably, wrong. Most, if not all, textbooks define “socialism” as, “… a system based on government ownership of business and property.”

The idea that 19th century socialists were working for “government ownership of industry” is wrong. Consider Eugene Debs. As I mentioned, he is in all the textbooks, but they cover what he accomplished more than why he was a socialist. Debs believed that socialism meant collective ownership of industry which would better guarantee a democratic society and individual rights.

Big Bill Haywood described the purpose of the IWW as the “emancipation of the working class from the slave bondage of capitalism.” And Rose Schneiderman, saw socialism as providing the “right to live, not simply exist…” to have bread, and roses, too.

Calling for “collective ownership,” or the “emancipation of the working class,” and demanding a right to “bread and roses” are all opposites of wanting “government ownership.” Ask yourself, what worker would vote for “government ownership” when that worker probably understood that the government was already owned by the capitalists? Yet against all logic, textbooks still suggest that these socialists, men and women, were calling for a system of “government ownership of business and property.”

The Lawrence Textile Strike 1912

Realistic or not, socialists wanted to create a society in which workers could control their own fates. Here is a bit of what happened during the massive textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912. It was organized by the IWW. It is mentioned in “The Americans” as a sidebar titled “One American’s Story.”

Half of the 30,000 workers in the textile mills were young women between 14 and 18-years-old. Despite the fact that some were already malnourished, the millowners lowered their weekly pay and sped-up production. 20,000 workers representing forty nationalities went on strike. National leaders of the IWW, including 22-year-old Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, coordinated the struggle. Here is a short description of how the IWW overcame just one of many obstacles.

To prevent ethnic splits from developing, the IWW organized separate strike and relief committees for each nationality. They translated speeches and literature into every language. Strikers threw up massive picket lines around the mills, and regularly paraded through the city streets.

Millowners and government officials mobilized a massive counterforce. When a woman was shot and killed on the picket line, union organizers (not the shooters) were charged and jailed as “accessories to the murder.” Martial law was declared in Lawrence, Massachusetts and all public meetings were banned. When the state militia was called in, a militia man killed a 15-year-old Syrian boy with his bayonet. Following a good deal of publicity, the millowners agreed to a settlement.

Future strikes became even more contentious and union victories became more difficult. The owners learned how to set multilingual and less-skilled immigrants against English-speaking craft unions. They hired increasingly brutal private security forces like those from the Pinkerton Agency to infiltrate unions, act as armed guards and keep strikers confused.

The Communist Party of the United States

The Communist cause [in the United States] attracted egalitarian idealists, and it bred authoritarian zealots.

Reds: The Tragedy of American Communism

Maurice Isserman 2024

The Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) was legally founded in 1919 in the midst of the Russian Revolution.

If you were unaware of a legal American Communist Party, you are not alone. Both textbooks currently on my desk fail to mention it. The inconvenient fact of a legal founding was also absent from every textbook I was given to work with in 35 years of teaching. Instead of legality, the textbooks are full of negative references to “communists” and “suspected communists” steering students to believe that communists were both illegitimate and illegal.

Historian and former young communist, Theodore Draper writes that, in the beginning, “American Communism was not very different in its methods and make-up from other American radical movements.” Meetings were openly held, but when the party openly advocated pro-union policies and laws against racial discrimination, they drew attention and condemnation by powerful economic and political forces in both government and industry.

In 1919 the Communist International (known as the Comintern) was founded in Moscow to coordinate revolutionary socialism worldwide. The CPUSA was expected to follow Comintern shifts in policy. Understandably, problems developed.

The motivations behind the CPUSA advocating pro-union and anti-racist policies were sincere. They believed that both positions would strengthen the working class and strengthen worker support for the Party. They also understood that the United States was vulnerable to well-deserved global criticism for widespread abuse of industrial workers, armed government intervention against strikes and virulent racism manifested in such things as Jim Crow Laws.

As a result, in the early years when the Comintern supported pro-union and anti-racist policies within the U.S., the CPUSA agreed. But when a WWII alliance between the U.S. and the USSR formed in the 1940s, the Soviets lessened their critique of American racism and the CPUSA followed suit. For many members this was not easy to take.

The American writer Richard Wright, for example, joined the party in 1933 largely because of its support for civil rights and anti-racist policies. In 1937, he became the Harlem editor of the communist newspaper, The Daily Worker.

He left the Party in 1942 because he correctly felt it had broken away from a policy of strong opposition to segregation and racism. Predictably, Wright’s experience as a communist is not mentioned in any high school history textbook that I have seen, but he wrote about his experience in an essay “I tried to be a Communist,” published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1944. The use of an excerpt might make for productive classroom discussion.

In the years that followed WWII, the Comintern would continue to match the shifting positions of Soviet foreign policy. And that continued to result in awkward policy pronouncements by CPUSA leadership. For example, General Secretary Gus Hall supported the unsupportable Soviet invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. His support of Soviet policy resulted in significant reductions in party memberships.

In “The Americans,” the 1956 Soviet invasion in Hungary is briefly mentioned but obviously without any mention of its effects on the CPUSA. The 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia is not mentioned. In “History Alive!,” neither action is mentioned.

It is nonsensical for textbook publishers to decline to explain that the CPUSA was founded legally. It is counterproductive for publishers to fail to mention that CPUSA contributed to organizing industrial unions and in doing so the textbooks omit important parts of American political and social history.

Unsurprisingly, the American government finally got around to formally going after the Party with the Communist Control Act of 1954. For a while it made membership illegal, but it is not even mentioned in texts. Eventually, in 1973, Congress repealed most provisions of the act and a federal district judge in Arizona ruled that the act violated the Constitution, but that decision has never been brought up to the Supreme Court.

Working-Class Heroes: The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and A. Philip Randolph

The previously mentioned AFL policy of organizing by craft unions remained in place until 1935 when the all-Black Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was granted membership. The BSCP was led by the great A. Philip Randolph, who played a leading role in the movement for racial equality, first within the labor movement, and then in the larger society.

Randolph was also a member of the Socialist Party (SPA). In 1917, with support from the SPA, he founded an important African American labor magazine The Messenger. He ran on the Socialist Party ticket for New York State Comptroller in 1920 and for Secretary of State of New York in 1922.

A. Philip Randolph is in every text, but the fact that he was a socialist, founded an important socialist magazine and ran for office as Socialist Party candidate is in no textbook I have seen.

American Communist: William Z. Foster

One former IWW member, and a future General Secretary of the American Communist Party, William Z. Foster is mentioned once in “The Americans” in connection to the steel strike of 1919 when he was still with the AFL and organizing steel workers. A vote, in August 1919, was almost unanimous in favor of stopping work. When the steel companies refused to meet with union officials, 250,000 steelworkers went on strike. Foster is not mentioned in “History Alive!“

The strikers were attacked by state and local mounted police and within ten days, 14 strikers and sympathizers were dead. The police-led attacks are not mentioned in my textbooks. I suspect that may have led a number of students to assume that it was the strikers who were fomenting violence.

The steel strike ended in January 1920 and in that same year Foster established the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL) which continued efforts to organize industrial trade unions of both skilled and unskilled labor.

In 1921, Foster attended a conference of the Red International of Labor Unions in Moscow. When he returned, he joined the American Communist Party (CPUSA). From that point forward he is not mentioned in either textbook. Nothing is mentioned, even when he became the General Secretary of the CPUSA in 1929 and nothing is mentioned when he legally ran for president of the United States on the Communist Party ticket in 1924, 1928 and 1932.

In 1929, Foster’s TUEL became the Trade Union Unity League TUUL (by replacing the word “educational” with “unity”). TUUL organized more than a dozen separate industrial unions all of which viewed class struggle as a unifying experience for workers. Most of them had little long-term impact. According to a former communist organizer, Dorothy Healey, we “didn’t understand the need for consolidating our gains, to make our unions serve the workers as a union…”

Which Side Are You On?

I want a better America, and better laws,

And better homes, and jobs, and schools,

And no more Jim Crow, and no more rules like

“You can’t ride on this train ’cause you’re a Negro,”

“You can’t live here ’cause you’re a Jew,”

“You can’t work here ’cause you’re a union man.”Dear Mr. President 1942

Pete Seeger

Folksinger 1940 to 2014, Communist 1936 to 1949, Soldier 1942 to 1945

In this article I have focused on how the roles played by the American Left in establishing the rights of labor are portrayed in high school textbooks. In short, the coverage is not good. The essential roles played by the left are largely ignored, but it is not simply the positive contributions of socialists and communists that are missing. High school history textbooks tend to distort the history of labor as a whole.

The conclusions of a 2011 study by the Albert Shanker Institute are still valid today. That study concluded that if labor issues are included in textbooks, the history is distorted in at least three ways. 1) Labor disputes are often seen as inherently violent. 2) The role of labor in winning social protections (such as, making child labor illegal) is largely ignored. 3) Little attention is paid to unionism after the 1950s.

Victor G. Devinatz, a professor of management at Illinois State University wrote about why left-leaning unions were historically repressed by both employers and the American government.

Much of this repression has occurred in response to union militancy during strikes, some of which was connected to political radicals of various stripes, including socialists and anarchists. Examples abound of this repression, which included employer and government violence directed against striking workers, such as the 1877 St. Louis Railroad Strike, the 1886 Haymarket Square Riot, and the 1892 Homestead Strike.

Professor Devinatz is correct in describing the anti-union activities approved of by both owners and American authorities. Although some of the “employer and government violence” is covered in some of the textbooks, they often describe the violence without clearly identifying who is responsible.

Textbook credit is usually given to Eugene Debs and the Socialist Party at the beginning of the 20th century, but the party was always more than Eugene Debs and the textbooks should make that clear.

As I have written, the American Communist Party was established legally in 1919. Yet, I have yet to see a textbook that includes that information. My guess is that since the textbook publishers did not tell the students that the Communist Party was founded legally, they decided not to mention even the most well-known American communists and then decided to leave out much of what they did in labor unions and in working for racial equality. Out of sight, out of mind. Out of books, out of memory.

Contemporary textbooks clearly downplay the contemporary American Left. In 2025 that means downplaying Democratic Socialists, who work to advocate for social and economic justice, improve working conditions and improve the ability of labor unions to organize and negotiate contracts.

If you would like to test the accuracy of what I have written, ask any recent high school graduate what they know about unions. Try to get them to cover both history and current conditions. My bet is that you are likely to get a response that means, essentially, that they know very little or nothing. In states like California, where courses in economics and history are graduation requirements, that response suggests malpractice.