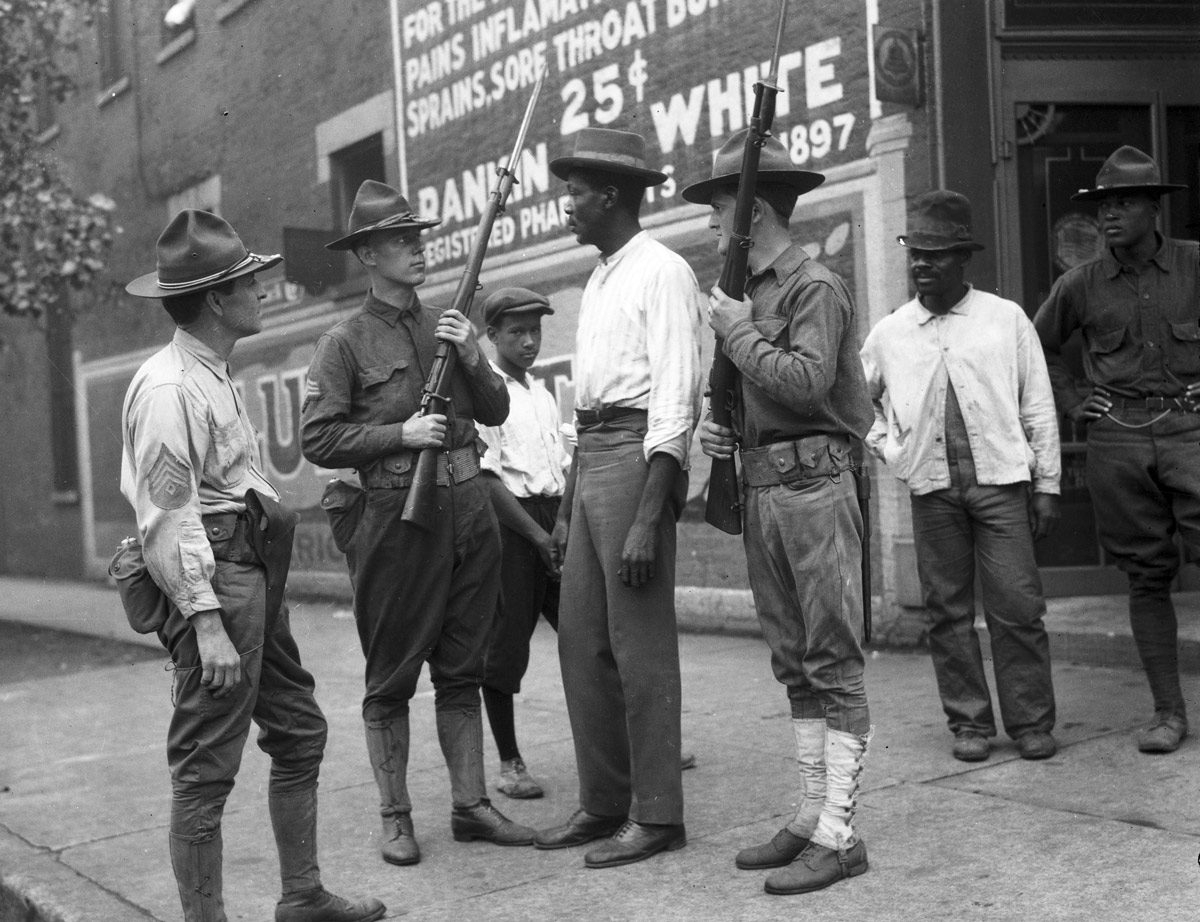

Above photo: National Guard during the 1919 Chicago Race Riots. Jun Fujita, courtesy of Chicago History Museum.

This is the third of three articles on how the American Left is remembered, or not, in high school textbook American History.

Part III is focused on the roles played by the American Left in working to establish civil and human rights in this country. Read Part I and Part II.

Establishing Civil And Human Rights

As long as the Negro here was passive the true solution of the race problem could wait… The South burned and lynched … But now, with the Negro openly resolved and prepared to resist attacks upon his person and privileges, the condition assumes a graver aspect.

Jean Toomer

Reflections on the Race Riots

New York Call, August 1, 1919

Is it not predictable that when segments of a population are harassed, marginalized and enslaved, they will eventually revolt? Does that not constitute a demand for justice?

According to American historian Herbert Aptheker, in North America from the 1600s to the end of the Civil War, there were at least 250 revolts each involving at least 10 enslaved persons.

The largest revolt of about 500 enslaved people took place in Louisiana in 1811. All of these rebels, widely cursed by those in power as threats, might better be remembered as America’s Black huddled masses, yearning to breathe free.

Throughout American history episodes of racist violence intensified when African Americans — and other people of color — made legitimate claims to full citizenship. In the twentieth century, given the right conditions, any of those incidents should have triggered a renewed civil rights movement, but for a variety of reasons, most did not.

In what follows I will explore three examples of racist violence that failed to get the attention necessary to force change: The Red Summer (1919), Scottsboro (1931) and Emmett Till (1955). Each is an important part of our history, yet none are examined honestly in textbooks. Each received some publicity at the time, each activated the community involved and received support from concerned outsiders including socialist and communist organizations, but that was as far as it got. Years later, most events and many participants are, essentially, forgotten.

Conventional American history is now firmly tied to those events that were chosen to be remembered. The forgotten are not mentioned in textbooks, but their lessons remain essential if we are to understand who we are.

The Red Summer Of 1919

More than 200,000 African-Americans served in Europe during World War I, but given continued federal and state government support for segregation, Black volunteers were not allowed in combat alongside the white American troops. Early on they were assigned to do manual labor, but eventually, about 40,000 served in combat alongside French troops and under French command.

According to Cameron McWhirter, in Red Summer, when these soldiers returned to the United States, they believed their participation in the effort “to make the world safe for democracy” had earned them the equal rights they had been promised in the Constitution since the close of the Civil War.” Many of these men, having experienced a different reality fighting alongside French troops, returned as visceral opponents of continued racial discrimination.

Instead of equal rights they returned to face angry white mobs in what is called the Red Summer of 1919. Newspaper accounts, government documents and NAACP files show at least 25 major riots erupted in 25 cities. “In almost every case, white mobs—whether sailors on leave, immigrant slaughterhouse workers, or southern farmers—initiated the violence.” Law enforcement failed to stop it.

According to an NBC report, the Red Summer amounted to “some of the worst white-on-black violence in U.S. history …. [with] Hundreds of African American men, women and children … burned alive, shot, hanged or beaten to death by white mobs.”

The groups, including socialist and communist organizations, who opposed the violence and understood the need for self-defense, were portrayed by the government, not as allies, but as agitators. The government even “began working with local authorities and gun dealers across the country to block the sale of weapons to African Americans.”

Historian David Krugler found that, “Military Intelligence and the Bureau of Investigation” deluded themselves into believing that the Red Summer was, in reality, a threatening Red Scare.

Intelligence officers, certain that socialists and communists were urging African Americans to take up arms, mistakenly believed that a revolution was imminent, that blacks across the country were conspiring to attack whites.”

Of course, it is the Red Scare rather than the Red Summer that shows up in the textbooks. Perhaps making matters worse, “The Americans” goes on to hyperbolically report that, following the Russian Revolution, there was a Communist call for international revolution which resulted in “about 70,000 radicals join[ing] the newly formed Communist Party in the United States.”

While it is true that the Bolshevik Revolution inspired other revolutionary movements, I cannot find any reliable source verifying such a large number of American Communists in 1919. I did find that the party “expanded its influence, particularly among industrial workers, immigrants, and African-Americans.” But not until the 1930s did the Communist Party (CPUSA) reach “an estimated 70,000 members.”

It is however certain that, in 1919, the newly established communist government in Russia provided Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer a handy scapegoat and mainstream newspapers followed his lead. For example, even after hundreds of African Americans were injured, at least 38 were killed and about 1,000 Black families lost their homes, The New York Times claimed the real cause of the unrest was “Soviet influence.”

Why is the Red Summer ignored by textbook publishers? Perhaps because African Americans, who were attacked, defended themselves by whatever means they had. Or perhaps because there were several cases of beatings and lynchings of veterans in their uniforms. Or perhaps because these racist “white riots” contradict the commonly used justification for the U.S. entering WWI “to make the world safe for democracy.”

The Jamaican-American socialist poet Claude McKay responded to the Red Summer by writing a sonnet entitled “If We Must Die”. It was published in the socialist magazine, The Liberator. I’ve yet to find it in a textbook. Here are four lines:

If we must die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot …

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Scottsboro Boys: 1931 To 2013

In 1931, nine African American teenagers were falsely accused of raping two white women on a train. The case drew some national and even international attention. The American Communist Party (CPUSA) quickly organized a defense. They were later joined by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) both in raising funds and mounting legal challenges.

According to the Cornell Law Forum:

No crime in American history – let alone a crime that never occurred—produced as many trials, convictions, reversals, and retrials as did the alleged gang rape of two white girls by nine black teenagers on the Southern Railroad freight run from Chattanooga to Memphis on March 25, 1931.

According to the National Museum of African American History:

The case of the Scottsboro Boys, which lasted more than 80 years, helped to spur the Civil Rights Movement. The perseverance of the Scottsboro Boys and the attorneys and community leaders who supported their case helped to inspire several prominent activists and organizers.

Yet, Scottsboro is mentioned in very few high school history textbooks. In “History Alive!” it is absent. In “The Americans,” the case is relegated to a sidebar where nothing instructive is reported, only that nine African American men were accused of “raping a white woman.”

Typical of textbook narratives, that is not exactly true. These “men” ranged in age from 12 to 20. They were, essentially, teenagers with names: Haywood Patterson, Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Willie Roberson, Andy Wright, Ozzie Powell, Eugene Williams, Charley Weems and Roy Wright.

Only four of them were known to each other prior to being accused. In fact, they were riding in different parts of the train as it passed through Alabama. Nevertheless, they were all accused of raping two young white women who were also not even in the same railway car as most the accused.

The textbook continues its careless reporting, suggesting that on the day of the trial the accused “met their court-appointed lawyer for the first time.” In reality, there were two lawyers and both had agreed to “advise” the defense rather than be the defense. The first, Stephen Roddy, was a real estate lawyer, unfamiliar with Alabama criminal law and widely reported to be drunk during the trial. The second, Milo Moody, was a 69-year-old who had not practiced law in years.

Within days, there were demonstrations in the United States, Germany, Spain and the USSR. Despite the lack of any evidence and despite the fact that one of the women (who was 17-years-old at the time) convincingly recanted her testimony, eight of the nine defendants were convicted and sentenced to death. The youngest defendant (Roy Wright) was granted a mistrial, perhaps because he was 12 years old.

In 1932 the Supreme Court, in Powell v. Alabama, ruled that they had been denied due process due to ineffective counsel.

At the same time James S. Allen (a pseudonym for Sol Auerbach) had established an office in Chattanooga, Tennessee with the intention of founding a communist newspaper to be called the Southern Worker. That turned out to be difficult, but Allen was able to devote extensive coverage to the Scottsboro trial. Here is a fascinating copy of one edition.

The obvious injustice attracted the attention of the International Labor Defense (ILD), a legal advocacy group established in the southern United States by the Communist Party USA. The ILD had already defended Sacco and Vanzetti and was active in anti-lynching campaigns. They took the lead in organizing the Scottsboro defense and hired prominent (non-communist) attorneys Walter Pollak and Samuel Leibowitz. Other attorneys, including George Chamlee were hired to deal with appeals and retrials.

Other civil rights groups (primarily the NAACP and the ACLU) subsequently provided support both during the trial and, more importantly, during multiple appeals and retrials. According to a PBS documentary, by the time the NAACP decided to become involved, the ILD had already organized a legal defense. In 1935 the various groups came together as the Scottsboro Defense Committee.

After 45 years in prison, in October of 1976, the last surviving defendant, Clarence Norris, was pardoned by Alabama Governor George Wallace. He died in 1989, but legal actions related to the Scottsboro convictions continued culminating in posthumous pardons in 2013.

Why do most textbooks ignore or minimize the Scottsboro case? Perhaps because you can’t tell this story honestly without crediting the Communist Party. Or perhaps because the case was too vivid an illustration of American racism in the 1930s. Or perhaps because during the series of retrials and reconvictions, the innocent Scottsboro boys collectively served more than 100 years in prison.

The Lynching Of Emmett Till

I recall my first look at his battered face

A few years younger than Emmett Till

When he met his brutal fate

That photograph scared me so bad

I started to cry

What a way for a boy like me

To have to dieEmmett’s Ghost

Eric Bibb 2021

I was 8 years old when my father told me about 14-year-old Emmett Till’s brutal murder. Some months earlier we had visited his ailing mother in Jackson, Tennessee. I asked him why he had moved to Los Angeles after the war, but I don’t remember if he answered my question then.

A year or so later he answered by showing me an open-casket photograph from Emmett Till’s funeral, published in Jet magazine. He said, “This is why I can’t live in the South” and then went into some detail about how the Klan had made life impossible. I have never forgotten that photo or the fact that my father showed it to me.

But somehow Emmett Till’s torture, murder and lynching never made it into the textbook curriculum. Even when I was in high school, in the 1960s, less than a decade removed from the murder, Emmett Till was never mentioned. And there is no mention of his killing in the newer textbooks now on my desk. Emmett Till is part of our history, but deliberately never mentioned.

In the late 1980s, the television series “Eyes on the Prize” contained a segment on Emmett Till. After I was able to get a copy, I never failed to use it in my classes. I’ll bet some of my students remember that photo, the one that scared Eric Bibb and the one that scared me.

The Daily Worker, published by the Communist Party USA, highlighted the racial injustice that was prevalent throughout the country, but especially in the South. On Sept. 11, 1955, the lead article was titled “Lynching of Fourteen-year-old Boy Arouses Nation” which reported on the public viewing of Till’s body.

From the start, the NAACP was involved in the prosecution of the accused murderers. NAACP field secretary, Medgar Evers, worked to secure witnesses. The New York Times and other mainstream newspapers published commentary on the case, but almost all of the groups and organizations that mobilized were communist, progressive, socialist or African American.

In the digital files from the Eisenhower Library, there is a relevant letter written by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, to President Dwight Eisenhower by way of Dillon Anderson, a special assistant. The letter explains how various organizations, including the Communist Party, were responding to the Till murder. It is clear that parts of the government were paying attention to reactions, in the public and the press, to racially charged events. Here is an excerpt:

The Communist press is giving widespread publicity to the Till case. The Daily Worker for September 9, 1955, carries an article, reflecting that the New York City Councilman Earl Brown had urged picketing of the White House to protest the lynching of Till. The same issue of the “Daily Worker” carries a statement of the national committee of the Communist Party, which was signed by William Z. Foster, national chairman, and which urged “federal and state intervention against Mississippi Lynchers.”

Why is the story of this lynching of a 14-year-old not part of the textbook curriculum? Perhaps because the victim was Black? Or perhaps because the white “accused” killers were acquitted? Or perhaps because the mainstream press didn’t reprint the photographs? Or perhaps because those images were considered too graphic for television? Or perhaps because, in contemporary MAGA-speak, the story might make white students feel bad for the wrongdoings of other white people.

In “Let the People See,” a book on Emmett Till by Elliott Gorn, he reported that there were stories published in 1956 based on a paid interview with the two men charged with the murder, in which Till was “characterized… as a defiant sexual aggressor.”

The lynching did resonate with some significant figures. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, for example, both cited the killing as motivation for more active resistance. King wrote that “Long repressed feelings of resentment… which had for so long cast a shadow on the life of the Negro community gradually were fading before a new spirit of courage and self-respect.”

Emmett Till’s murder also led to protests and organizing efforts. Labor unions, particularly left-leaning ones like the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA), condemned the murder and participated in civil rights advocacy.

Left Wing Civil Rights Activists Left Out Of Textbooks

There were thousands of Americans who identified themselves as communists, socialists and independent leftists and many played vital roles in civil rights causes in the 20th century. Most of them never appear in any textbook. Here are three who belong, but there are many others.

Lovett Fort-Whiteman (1889-1939)

Fort-Whiteman was born in Dallas in 1889. He moved to New York City in 1910 and joined the Socialist Party of America (SP) in 1917. In New York, he found himself in the company of Socialist Party leaders and became well-acquainted with A. Philip Randolph who, along with Chandler Owen, founded The Messenger. In 1918 Fort-Whiteman became Dramatic Editor of the paper.

After speaking to a small group associated with the Communist Labor Party, Fort-Whiteman was detained and charged with violating the Espionage Act by advocating “resistance to the United States.” According to Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, in “Defying Dixie” he remained in jail “for months.” Hopefully readers can appreciate the irony of a direct descendant of slaves being charged with “resistance” to the United States.

The 1919 Red Scare and the upsurge of racial violence against the African-Americans led a 24-year-old J. Edgar Hoover, then of the Bureau of Investigation (later to be called the Federal Bureau of Investigation), to closely watch Black radicals. Again, according to Gilmore, Hoover’s fears coalesced into the person of Fort-Whiteman: Black, socialist, part of the IWW, and soon to be a communist.

On Oct. 10, 1919 his appearance at the Jewish Labor Lyceum, sponsored by the Communist Labor Party, drew a small audience of a dozen, but everyone in the meeting hall was arrested. This happened at the same time as the Red Summer’s white riots. Attendees were later released, but Fort-Whiteman and one immigrant attendee were held for months on charges of sedition. The charges were eventually dismissed.

In June of 1924 Fort-Whiteman traveled to Moscow as a delegate to the Fifth World Congress of the Third International. On July 1 he addressed an audience on “the Negro question” in the United States. He stayed in Moscow at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East.

By the 1930s, while in the USSR, he became involved in inter-party conflict over future projects, unfortunately this coincided with the Great Purge in the Soviet Union. His side lost. He was arrested and tried in 1937 and was sentenced to five years of hard labor at a gulag in the gold-mining fields of Siberia. In 1939 he died there of “heart failure.”

Harry Haywood (1898 – 1985)

Harry Haywood was born in Nebraska in 1898 to formerly enslaved parents. In 1913 after his father had been attacked by whites, the family moved to Minnesota and then to Chicago. In WWI he served in the 8th Infantry, a Black regiment of the Illinois National Guard.

When he returned to Chicago, he was radicalized by the Chicago race riot which was just one episode in the “Red Summer” of 1919. This is how he began the prologue of his autobiography, “Black Bolshevik”:

On July 28, 1919, I literally stepped into a battle that was to last the rest of my life. Exactly 3 months after mustering out of the army, I found myself in the midst of one of the bloodiest race riots in US history. It was certainly a most dramatic return to the realities of American democracy. Then it came to me, I had been fighting the wrong war. The Germans weren’t the enemy – the enemy was right here at home. These ideas have been developing ever since I landed home in April, and a lot of other black veterans were having the same thoughts.

Soon after that Haywood joined the Young Communist League. In 1925 he joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). His personal goal, as expressed in his writing, was to connect the political philosophy of the party with the issues of race.

In 1926, he and other African-American Communists, travelled to the Soviet Union to study the effects of communism and the Communist Party on racial conflict in the United States. Among the anticolonial revolutionaries he met while in Moscow was Ho Chi Minh. He stayed until 1930 as a delegate to the Communist International (aka the Comintern).

Here is Haywood’s reaction to news of the Scottsboro Boys upcoming trials. This is also from his autobiography. It gives the reader some idea of why he was an activist and why he led the Chicago movement to support the Scottsboro Boys.

It was only when confronted with the dispatch of the ILD and the communists, and taking up the case, and with the widespread outcry against the legal lynching, in all sections of the black population, that the NAACP belatedly tried to enter the case and force the Communists out.

We communists viewed the case in much broader, class terms. First, we assumed the boys were innocent – victims of a typical racist frame up. Second, it was a lynchers’ court – no one, innocent, or guilty, could have a fair trial in such a situation.

From the beginning we called for mass protest against the social crime being acted out by Wall Street’s Bourbon henchman in the south. On April 2, the Daily Worker called for protests to free the boys. Again, on April 4, the Southern Worker carried an article that characterized the case as a crude frame-up.

When eleven Communist leaders were tried under the Smith Act in 1949, Mr. Haywood was assigned, by the Party, the task of research for the defense. In the late 1950s, he and others were driven out of the CPUSA. He worked with Malcolm X from 1964 until his assassination in 1965. He published his autobiography ”Black Bolshevik” in 1978.

Mr. Haywood had volunteered to fight in three wars. In WWI he served with the Eighth U.S. Regiment. In the Spanish Civil War, he fought with the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. During WWII he served in the Merchant Marine. He died in January 1985 at the age of 87 and was buried (under his birth name of Haywood Hall) in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.

If textbooks publishers want students to engage with American history there are few figures more important than Harry Haywood.

Pauli Murray (1910 – 1985)

Pauli Murray was born in 1910 in Baltimore, Maryland. Rev. Murray was a human rights activist focused primarily on gender equality, legal scholar, author, poet, labor organizer, Episcopal priest, and LGBTQ+, multiracial Black person. The excerpt below is from a poem written in 1939.

Now you are strong

And we are but grapes aching with ripeness.

Crush us!

Squeeze from us all the brave life

Contained in these full skins.

But ours is a subtle strength

Potent with centuries of yearning,

Of being kegged and shut away

In dark forgotten places.To The Oppressors

Pauli Murray

As if a precursor to Rosa Parks in Montgomery in 1954, in 1940, Pauli Murray sat in the whites-only section of a Virginia bus with a friend. The police were called, but the two refused to move to the rear. They were arrested for violating segregation law, but were only convicted of “disorderly conduct” and were fined.

That experience helped lead Murray to subsequent involvement with the socialist Workers’ Defense League (WDL) and to a career in civil rights law. As a lawyer, Murray argued for civil rights and women’s rights. In 1950 she wrote a book titled, “States’ Laws on Race and Color” which NAACP Chief Counsel and future Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, called the “bible” of the civil rights movement.

In 1942, while still in law school, Murray joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and published an article, “Negro Youth’s Dilemma.” The article challenged segregation in the US military, which continued until 1948. In the 1940s Murray participated in sit-ins meant to challenge discriminatory seating policies in Washington, D.C.

In 1961, President Kennedy appointed Murray to the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1963 Murray wrote a letter to A. Philip Randolph which criticized the fact that no woman was invited to make a major speech at the March on Washington. This is from that letter:

I have been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grassroots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions. It is indefensible to call a national march on Washington and send out a call which contains the name of not a single woman leader.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg named Murray as a coauthor of the ACLU brief in the landmark 1971 Supreme Court case Reed v. Reed, in recognition of pioneering work on gender discrimination.

Pauli Murray had a life-long struggle with gender identity which is explained in the autobiography, “Proud Shoes”. After a brief, annulled marriage to a man, Murray had relationships with women. According to the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, given contemporary changes in pronoun usage, they write that, “We do not know how Pauli Murray would identify if they were living today or which pronouns Murray would use for self-expression.”

According to the Center, Murray self-described as a “he/she personality” in correspondence with family members. They also state that “Rev. Dr. Murray sought gender-affirming care in different ways throughout their life.”

In 1973, following the death of longtime life-partner Irene Barlow, Murray left a tenured position at Brandeis University to enter General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York.

Again, to quote from the Pauli Murray Center website, “In 1977, Pauli Murray became the first Black person perceived as a woman in the U.S. to become an Episcopal priest.” I can list at least a half dozen reasons Pauli Murray should be included in high school history textbooks and in high school English curriculum. What I have written above should establish what she brings to American history. As for the English curriculum, take your pick from here.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Undoubtedly one person who did as much as anyone to move the U.S. away from segregation and who tried to move us away from economic injustice, was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. While he is not neglected in history textbooks, his image has been conveniently transformed. Instead of being accurately portrayed as part of the American left, his image is that of an attractive young minister who becomes the charismatic leader of non-violent protest.

He was more than that. Dr. King was committed to a radical transformation of this country and he worked closely with long-time activists like Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker and Stanley Levison. All three of these left-wing activists spent their lives making the U.S. a better country.

Of course, two of them were accused of “communist ties” by American authorities. Rustin had been part of the Young Communist League from 1936 to 1941. He left the party, with many others, when the CPUSA reversed its anti-war and anti-racism policies before WWII. In 1959 J. Edgar Hoover accused Stanley Levinson of being a communist, but he denied being a party member.

On the next Martin Luther King Day, consider more than the traditional “I Have a Dream” speech. Below are three quotations to share with others at lunch or at dinner. The source documents themselves are also worth re-reading.

“We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

“Capitalism was built on the exploitation of black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor, both black and white, both here and abroad.”

The Three Evils speech, 1967

“I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.”

A Time to Break Silence, April 4, 1967 (Spoken exactly one year to the day before Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis.)

What Is To Be Done?

In this series of three parts, I have tried to focus on ways in which high school American history textbooks avoid discussing contributions made by the American left. As it turns out, when artists, writers, social reformers, critics of war or union leaders were socialists or communists, they were not identified as such, barely mentioned or ignored.

I have pointed out the deliberate misuse of social and political terms in textbooks as well as in contemporary political rhetoric. In both, there is a lack of realistic definitions for the most fundamental terms like democracy, capitalism, socialism and communism. Over years that ambiguity has become normalized. Textbooks avoid controversy and one-dimensional politicians pretentiously appear serious-minded.

Such inadequacy makes it difficult, if not impossible, to function as a democracy. We are living in a dangerous version of Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. No longer do we simply live with an arrogant emperor convinced he is wearing fancy clothes that only the smartest and best can see. No longer can we expect a child to cry out the unambiguous truth.

We need more than a few of us to demand verifiable definitions and real-life examples from politicians, teachers and textbooks. After all, if we do not share legitimate definitions and common understandings, we cannot engage in real conversations, let alone have honest debates.

At the most basic level, our schools and our textbooks should teach students, in the words of Dr. King, the true meaning of the American creed. While I trust that when Dr. King identified that creed as “all men are created equal” he meant “all people are created equal,” I’m equally confident that when Jefferson wrote that phrase he meant “all white men.”

That difference is the result of multiple progressive political, cultural and legal changes made over more than two hundred years, but in our current climate, when many in positions of power are demanding that we move backwards, we must be explicit about things like who has been created equal. The contemporary meaning of that must be inclusive and stated clearly.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all people, everywhere, are created equal and are endowed with unalienable rights including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.