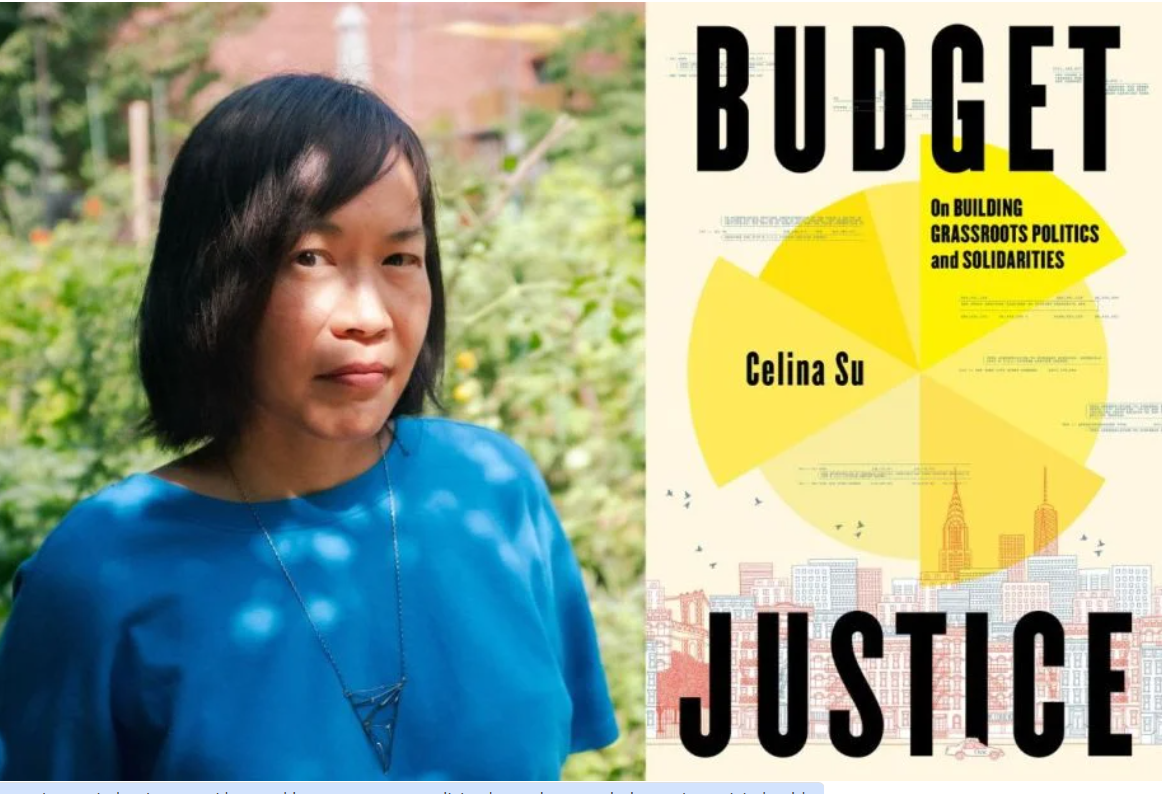

Above photo: Celina Su, “Budget Justice: On Building Grassroots Politics and Solidarities.” Princeton University Press.

New York’s participatory budgeting experiment shows there are no shortcuts.

And no algorithmic fixes for building democratic power, Celina Su writes in her new book.

How might everyday city residents begin to demand transparent, equitable city budgets and fight austerity? In my book “Budget Justice: On Building Grassroots Politics and Solidarities,” I examine real-life struggles for city budgets that give everyone, especially those from historically marginalized communities, resources and power to address their needs.

Part of the book draws upon a decade of fieldwork on participatory budgeting —in which everyday residents, not just elected officials and civil servants, allocate public funds. Since the 1990s, more than 11,000 cities and communities around the world have turned to participatory budgeting to hold local governments accountable.

I especially draw lessons from the New York City Council-led participatory budgeting process, called PBNYC, by far the largest participatory budgeting process in the United States. To be impactful, experiments like PBNYC must be funded well and nurtured alongside other existing efforts, like budget hearings and mutual aid networks, in larger ecosystems of participation.

Further, they hold the potential to help cities to combat austerity when they focus not on small, individual projects, but on how to help everyday residents to connect with one another, organize themselves and build power.

Impressive achievements in outreach and enfranchisement

PBNYC began in 2011, when four council members decided to run participatory budgeting processes in their respective districts. By 2016, 31 of 51 council members participated in such processes; since then, the percentage of districts involved in participatory budgeting has remained fairly stable, despite dips in participation during the pandemic and substantial turnover in elected officials.

What does PBNYC look like in practice? Each year, each participating council member devotes at least $1 million of their discretionary funds to participatory budgeting. For the most part, PBNYC funds so-called capital projects (physical infrastructure, rather than staffing or programming, with a lifespan of at least five years). Typically, residents meet in assemblies to share ideas about community needs and community projects each fall. Over the winter, volunteers deliberate in groups to vet and further develop some of these ideas into ballot items. Each spring, all residents ages 11 and up vote for the PBNYC projects they most want to see realized; those with the greatest numbers of votes get funded and implemented.

PBNYC showed that everyday residents are far from apathetic about politics. When they know that they can make a difference, they show up. Strikingly, almost one-quarter of participatory budgeting voters in 2015 had a barrier to voting in regular elections, largely because of age or lack of U.S. citizenship. One-third were foreign born. In one district, over two-thirds of distributed ballots were in languages other than English.

As compared to other typical modes of civic engagement, PBNYC was remarkable in helping residents to engage not only government differently, but also each other in new ways. Half of participatory budgeting voters surveyed state that they had never worked with neighbors on a community issue before.

Still, even as they asserted that participatory budgeting was a transformative experience for them, many PBNYC participants also stated that they were making little impact on housing, affordability and the urgent needs that sparked their interest in participatory budgeting in the first place. They felt like their more innovative or pressing project ideas were too readily dismissed as ineligible, too ambitious or simply “unrealistic.”

The New York case, then, also forces citizens to ask crucial questions regarding participatory and deliberative democracy: Participation for what? Whose projects get taken seriously, move forward and get funded?

Lessons from the PBNYC case

These tensions point to lessons not only for New York, but other cities as well.

Participatory budgeting must be expanded and deepened beyond its current design. Currently, participatory budgeting often remains the exception to typical municipal budgeting: a way for constituents to voice concerns, let off steam and see some of their ideas come to fruition while most of the budget remains opaque and predetermined.

If New York were to match the 45 euros per capita participatory budgeting funding in Paris, for instance, it would invest around $50 for each of almost 8.1 million residents into participatory budgeting, yielding $400 million to be decided by New Yorkers each year.

This robust version of a New York participatory budgeting process would be roughly 10 times bigger than it currently is. It would thus not be a side exercise, but instead a core budgeting process for the city.

By focusing exclusively on the invest side of the equation, participatory budgeting remains incomplete. It therefore risks propagating the myth that the problem is solely a scarcity of funds, rather than austerity as policy.

Participatory budgeting in the United States is not consistently tied to explicit questions of funds’ origins; eligible funds are frequently those deemed easy, limited, regressive, or discretionary.

In Vallejo, California, the citywide participatory budgeting process allocates proceeds from a sales tax. Other participatory budgeting funds have come from Community Development Block Grants. In other places, community groups have campaigned for participatory budgeting processes to allocate the proceeds of court cases where firms had to pay hefty damages. Participatory budgeting’s attention on investments must be accompanied by attention on revenues and divestments.

A deeper lesson is that there is no foolproof algorithm for participatory budgeting.

Communities must resist discourses of “best practices” or perfect institutional designs. Participatory budgeting must be practiced, maintained, and regularly tweaked to stay strong as well as relevant to changing political conditions.

Searching for perfect procedural rules deems participatory budgeting a technical project for “good governance,” not a political project for racial and economic justice.

Meeting the political moment

In fact, Brazil’s decades-long experiences with participatory budgeting suggest that even institutional designs and rules that are nearly perfect in one context can flounder in another. The scope along with the role of participatory budgeting in local governance must be adjusted to fit local and current needs.

In the case of Porto Alegre (where municipal participatory budgeting was born in 1989), the original scope of the process focused on capital infrastructural projects because that is what the city needed at the time. Participatory budget-funded projects involving street safety, water, and utilities helped the city to make remarkable progress in lowering infant mortality over a relatively short span of time.

In contrast, many of the community needs articulated in New York concern services and programming, not infrastructure. Quite a few constituents have complained that project eligibility rules have not fit their needs.

Further, the Porto Alegre participatory budgeting process was designed in a way that fit the political moment. The city boasted of a strong civil society — including social movement groups that helped topple the military dictatorship in Brazil in the late 1980s — that could be relied on for high rates of participation. The city also closed some other traditional channels of feedback, so that local organizations had to appeal to the local government for funds, in front of everybody else, through the local participatory budgeting process. That is, there were no backroom city budget negotiations because the local government closed the back rooms.

In other words, participatory budgeting cannot bring about budget justice as a democratic experiment in a larger administrative state that otherwise remains unchanged.

As experiments like participatory budgeting become widespread or even trendy, communities must also remain vigilant against their co-optation. City governments already know that they should not make major decisions or approve large developments without at least the semblance of community input. But that does not mean that their processes are truly participatory, even if they call them so.

This increases the chances that they become “technocratically canned,” robbing them of the reason and power of why they were invented in the first place. As sociologist Henri Lefebvre notes, perfunctory public participation “allows those in power to obtain, at a small price, the acquiescence of concerned citizens. After a show trial more or less devoid of information and social activity, citizens sink back into their tranquil passivity.”

Or perversely, they risk further alienating rather than engaging citizens.

Navigating paradoxes of participation

Quite a few paradoxes of participation arise — that in most cases, those who might benefit most from political participation tend to participate least, and relatedly, that in contrast to holding politicians accountable, participatory channels sometimes give them the cover (or less generously, the gall) to wash their hands of the provision of essential services.

In such instances, some policymakers attempt to claim that all negative outcomes should now be attributed to citizens since they helped inform decisions. While some pundits proceed to claim that “community input is bad, actually,” democracy scholars show that it is by no means inherently so. At the very least, participatory venues must not be set up to fail—with insufficient funding, crunched timelines, little outreach, little training or helpful information provided, incompetent facilitation or attention to power inequalities and preorganized groups, and tokenistic representation.

These trends serve as a reminder that spaces for democratic participation must themselves be democratically governed. As cultural theorist Stuart Hall wrote while analyzing English Labour and Social Democratic Party strategies, “‘Participation’ without democracy, without democratic mobilization, is a fake solution. ‘Decentralization’ which creates no authentic, alternative sources of real popular power, which mobilizes no one. … Its function is to dismantle the beginnings of popular democratic struggle, to neutralize a popular rupture.”

One meme that emerged online in 2021, a year after the uprisings in George Floyd’s name, declared, “We demanded racial justice; we got an Office of DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] instead.”

One can imagine many corollaries, at different scales: “We wanted budget justice; we got participatory budgeting instead.” “We demanded participatory budgeting; we got laptops and water fountains instead.”

Amplifying the ‘spillover effects’

Indeed, because the PBNYC process remains so limited, many of the more interesting and profound outcomes thus far take the form of spillover effects — that is, proliferating demands and practices that formally fall outside the participatory budgeting process, but would not have happened without it.

Based on my research, constituents routinely became informed citizens through participatory budgeting, but they also became so indignant or even enraged by the budget injustice they witnessed during the process, that they became politicized in new ways because of it.

For instance, participatory budgeting participants — perhaps especially those who had no personal connections to local schools—were shocked by the conditions of school bathrooms, with issues like stalls without doors. They were upset about putting participatory budgeting discretionary funds toward such basic needs. The participatory budgeting process mobilized them around this concern; in the fourth participatory budgeting cycle, the Department of Education doubled its allocation for school bathrooms. This was explicitly because of participatory budgeting.

In another example, City Comptroller Brad Lander’s own experiences as a council member inspired him to develop an online tracker for the timelines and spending of participatory budgeting-funded capital projects in his district. He then advocated for a citywide version and sponsored a law mandating its creation. The online Capital Projects Dashboard, which came out during Lander’s term as city comptroller, merges budget information from the city’s Financial Management System with cost, current phase, and details from agency project management databases. It is exactly the sort of interactive, accessible information portal I yearned for when I first tried to make sense of the city budget.

Some PBNYC projects explicitly aim to trigger larger ripple or spillover effects. One successfully funded project, called “Youth Organizing for Menstrual Equity. Period” (with the pun intended), aimed to “create youth-led workshops for middle-schoolers to discuss period stigmatization [and] medical racism.” The project thus sought to empower youth to advocate for further changes in school policies.

In another example, the ballot description for an elevator at a subway station in Brooklyn clearly states that winning participatory budgeting funds alone could not possibly pay for such an elevator; rather, people used participatory budgeting to “put pressure” on the public transit authority to fund the remainder of what would be needed to create the first accessible station in the council district. They succeeded.

While spillover effects cannot be guaranteed, their presence is crucial. They serve as reminders of participatory budgeting as both a school (and boot camp even) and laboratory of democracy. Cities can thus amplify the impact of limited participatory budgeting processes by encouraging projects that, in turn, organize residents to engage other spaces — like budget hearings, mutual aid networks, tenants unions, community boards or wage councils — in a larger ecosystem of participation.

No shortcuts

When the means determine the ends, there can be no shortcuts.

In order to enact public budgets that facilitate collective care and well-being, cities must help citizens to think together about collective needs, learn about city budgets, articulate what they wish to divest from and invest in instead, and work beyond small, “cute” projects. Meaningful participatory budgeting only takes place when policymakers invest resources, thoughtful designs for engaging interactions with citizens, and real decision-making power into the process.

With those non-negotiables in place, communities that put in the effort reap rewards in spades — in fruitful projects that improve material conditions in the city in sensitive ways, new social and political connections, greater trust in one another and government, and even greater public willingness to pay taxes.

If the participatory budgeting process is not messy, if it is easily accepted by power holders as safe and doable, then it is not truly working. Budget justice requires grassroots politics that takes up invitations like participatory budgeting, but that also refuses to be managed from above. The driving question of means and ends for budget justice thus shifts from, Is participatory democracy possible? to, Are these participatory democratic institutions mobilizing? Do they help communities to organize themselves to combat austerity and opacity, articulate divest-invest formulations for city budgets as moral documents, and propose different logics for city budgets?

The rapid growth of new people’s budgets campaigns around the country, especially since the 2020 uprisings, suggests that many grassroots coalitions already have these questions in mind.

In addition to forwarding specific policy or budget platforms, they pay attention to participatory democracy, helping everyday residents to forward their perspectives and have a say in policymaking. Most of these people’s budgets also pursue participatory budgeting or people’s assemblies as part of their campaigns.

Paying attention to context does more than help participatory budgeting practitioners to implement more appropriate, sensitive, substantive and therefore successful processes. It also helps citizens to attend to struggles over budgets outside participatory budgeting or elections, across a whole range of democratic spaces, and to practice instances of budget justice that participatory budgeting simply cannot contain.

Adapted from “Budget Justice: On Building Grassroots Politics and Solidarities,” 2025, published by Princeton University Press.