Capitalism is fueled by crisis. Whether persistent or recurring, local or global, environmental or financial, crisis drives capitalism. It strengthens it, enabling it to adapt. Some view the uprisings that have exploded in recent years as signs of a new global resistance. They are mistaken. The uprisings index the global force of capitalism. For the most part, they are reactive expressions of hardship and declining expectations.

Organized resistance, particularly in a form strong enough to shift the balance of power, is hardly enough to register. When it does flare up, power uses the opportunity to justify the expansion of anti-terrorist infrastructure, contributing more to strengthening the capitalist state than to building the Left opposition. Small scale solutions – localism, co-ops, wind turbines and solar panels – while often pointed to as evidence of a possible alternative future, in themselves say nothing of the form of social relationships within which they exist. If anything, they co-operate with capital in creating new commodities, and providing new opportunities for the expansion and intensification of market relations. When they reinforce the given order of things, local, voluntary, and “green” solutions are embraced by power. When they don’t, they are ignored, abandoned, submerged, or quashed.

Capitalism is the only game in town. There is no alternative.

There are nonetheless indicators of some level of coordination occurring between movements, lessons that seem to be transferring from one uprising to the next, some connected infrastructure, some amount of collective self- awareness. There is enough evidence to push against the first reading of our contemporary landscape, suggesting that we might track these signs as if they actually pointed to something else, a newly emergent counter-power.

In this text, we treat the Occupy movement as a case study. We claim that there did exist a certain element within the movement representing a significant counter-power. This element propelled the explosive expansion of the encampments across the US and the world. To properly understand the force of this element, we first dissect some of the Occupy myths. This enables us to clearly distinguish between what made Occupy strong and what did not.

May 2012, Barcelona General Assembly, Hand Gestures

May 2012, Barcelona General Assembly, Hand Gestures

Video stills from Global Uprisings -http://www.globaluprisings.org/

The Weakness of Occupy

The conventional Occupy wisdom is that horizontal organization, a democratic consensus decision-making process, and the General Assembly (as a model of direct democracy that includes the People’s Mic) were the key to the movement’s ability to break out of its capitalist “hierarchical” setting. When asked, however, most of those involved describe an experience of these decision-making platforms as completely dysfunctional.

To Not An Alternative, this seeming paradox is not surprising. Over the last decade our work has involved researching, developing, and defending the claim that participatory democratic processes–from voting in elections to engaging in consensus-oriented discussions–fail to provide an alternative to capitalism. In fact, these processes are better understood as symptoms of the dominant ideology of communicative capitalism–that form of capitalism wherein democratic ideals are materialized in media and information networks so as to intensify and preserve the capital accumulation of the one percent. In and of themselves, democratic and participatory frameworks are not politically significant today. We are not trying to overthrow a king. As should be clear due to the proliferation of networks, power doesn’t confine itself to impersonal hierarchical structures. It’s diffuse and distributed, operating through us and on us. Participation can just as readily function as a vector for dominant ideologies as it can serve as a tool for liberation.

As it championed horizontality and participation, Occupy proceeded as if it were unaware of the ways power is and can be exercised. Echoing a critique of hierarchy common among Progressives, Occupy fell into the trap of acting as if power operates exclusively from above, that command and control emanate from some centralized, closed authority. Consequently, it’s no surprise that many latched on to notions of openness, transparency, and participation as radical ends in and of themselves. In so doing, they fetishized process over product, means over ends, when they should have focused on constructing a form that might at some point impact the dominant power structures. Fortunately, a nascent version of that form was given to the movement. It had nothing to do, however, with the processes widely construed as defining Occupy.

The General Assembly (GA), emblem of the Occupy movement, was the primary tool for achieving horizontal participation. In practice, as most Occupiers now agree, it did more to destroy the movement than anything else. Even as specific working groups were sometimes able to use the consensus process effectively (although many were not), the GA itself was a disaster.

The General Assemblies were notoriously dysfunctional. On the one hand, they were completely inclusive. There were no rules for membership. Anyone was welcome. Consequently, there was no mechanism by which to hold people accountable. Someone with an agenda to disrupt or derail the discussion (for example, participating undercover police), could easily do so. The challenge of achieving consensus among the disaffected and contrarian usually resulted in stalemate, inaction, or the adoption of the least controversial position.

On the other hand, the GAs relied on a constitutive exclusion: those who could not show up in person could not participate. Working people, whether waged or unwaged, in the paid-labor market or caring for others, were disadvantaged by the basic structure of the movement. And, because Occupy so celebrated direct democracy, those who could not attend were not even represented in the discussion. There were no procedures for discovering and considering their views.

The General Assembly staged the act of decision-making. It didn’t function as an effective process. In actual fact, organizers with power worked outside the GA to achieve their outcomes. They circumvented the very process they themselves claimed defined and legitimated the movement. So Occupy was never as horizontal as its rhetoric proclaimed. Some people had more influence than others. Some people made things happen and got others to follow. They were leaders. Not only did the GA fail to acknowledge this basic fact but its mythology actively concealed it.

The GA put the participatory process on display. This is what made it powerful. It provided a platform for people to express themselves under a common name. The expectation that the platform was to exercise a decision-making function, the conception of it as having an executive power, however, made participating in the GA process confusing and frustrating. There was a fundamental mismatch between platform functionality and user expectations. Any new person who showed up with the idea that the GA was a place to make things happen quickly realized that their input was lost in the cacophony of voices.

Rather than functioning in ways that could build collective expression, moreover, the GA was a site for individual expression. One person says something, then the next person says something. Any relation between the two statements is contingent at best. The second statement need not be a response. It need not engage the first one. More additive than responsive, prioritizing the addition of ever more speakers to a stack as if more views necessarily resulted in better deliberation, the GA provided a space for individuals to express their feelings, a place where they could be heard. It was not set up to facilitate brainstorming, the consideration of complex ideas, or the evaluation of action-proposals in the context of a dynamic political environment.

The primary practical innovation of Occupy Wall Street’s GA was the People’s Mic. Born of necessity—the inadmissibility of loudspeakers or bullhorns in the park—the People’s Mic involved the crowd repeating a speaker’s words so that people too far from the speaker to hear would know what was being said. In its idealized version, the People’s Mic was a vibrant form of collective speech and will-formation. In practice, it invited privilege and censorship. Participants, more specifically those standing closest to the speaker, don’t repeat all statements equally. Remarks that are disagreeable or unclear, for example, aren’t repeated. They are left out of the discussion. Conversely, the People’s Mic privileges remarks that are well-crafted, rhetorically satisfying, easy to transmit. Those fluent in the dominant language, not to mention those comfortable with public speaking, flourished in this setting. Those who were shy, uncomfortable speaking in front of large groups, those with speech impediments, heavy accents, or indirect, even convoluted speaking styles did not. In short, the People’s Mic elevated people with a certain set of rhetorical skills, enabling them to emerge as unacknowledged leaders.

Occupiers depended on the GA because decisions needed to be made, yet the GA was useless as a decision-making platform. The result was endless discussion, debates that went nowhere for weeks, stagnation and frustration. The way Occupiers wanted decisions to be made—openly and horizontally—failed to connect with actual practice. Rarely were actions the product of GA decisions. Instead, they were organized by independent groups skirting around the GA structure, acting in the name of the movement in a way completely counter to the movement’s self-proclaimed participatory principles. Had autonomous groups waited on the GA to make decisions, the actions and encampments across the country would never have emerged.

November 2012, Pulling up bricks in the streets of Portugal

Video stills from Global Uprisings -http://www.globaluprisings.org/

The Failure of Consensus

The myth of the horizontal process took hold during the first weeks of the Zuccotti Park encampment. People saw Occupy as something new. The belief that the General Assemblies and People’s Mic were new democratic forms helped Occupy spread. But when it came to making actual decisions, time after time and in occupation after occupation, the mismatch between function and expectation reappeared.

This became obvious to New York organizers when discussing direct action. The first OWS direct action meetings started with a GA that broke up into small groups facilitated by different people with action ideas. It was at this point that Occupiers for the first time were struck by the question that, if they didn’t know the people they were organizing with how could they trust them? How would they know whether someone in the group was an undercover cop? How they know if another person would show up when needed, would keep a promise?

Within a week of these first direct action meetings, an extremely rapid re-education of new organizers took place. It focused on a different process, one familiar to experienced activists, that of “security culture.” As part of the re-education process, pamphlets were produced and distributed that explained the importance of organizing actions that were not open, but were built instead on the affinity group model. Affinity group organizing is structured around groups of close, trust-worthy, friends. The premise is that not everyone needs to be included in every decision. Not everyone needs to know everything as an action is being planned. For successful actions, information is generated and distributed on a need-to-know basis.

This need to organize actions in secret clusters runs counter to the logic of the open platform. In Occupy, however, this contradiction was never seriously addressed. As a result, throughout the duration of the movement, accusations have been fired at groups for organizing actions in the name of Occupy that were not agreed to by the General Assembly. In a sense, a mindset was operative in the movement that simultaneously encouraged people to act autonomously and condemned them when they succeeded for not having secured approval in advance.

Another example of the disconnect between horizontalist myth and Occupy practice was the persistent self-denial with regard to the conditions that made the Zuccotti occupation possible. Some continue to insist that horizontality explains why the encampment survived the initial threat to evict occupiers from the park on October 14, 2011. This is a fantasy. In fact, while the GA debated what to do, organizers behind the scenes (without waiting for consent from the GA) jumped into action. The Working Families Party emailed its members asking them to bombard City Council Representatives and the 311 hotline with calls. MoveOn phone-banked its entire NYC list, telling them to go down to the park with trucks, mops, and cleaning supplies and to be there ready to “defend” the occupation at six am. And Avaaz dug up and distributed the personal phone numbers of the Brookfield property-owners. Had these groups waited for the GA to come to consensus there would have been no encampment left to discuss.

The Strength of Occupy

If the ostensibly horizontal processes of the GA were not the source of Occupy’s strength, what was? Our contention is that Occupy was powerful not where consensus worked but in instances where groups and individuals showed a commitment to a collective idea even when they disagreed.

When the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Greece, and Spain happened in 2011, people around the world became gripped by anticipation: where would we see the next revolt? Would it, could it happen in the US? The February occupation of the capitol building in Madison, WI fit easily in the pattern as it demonstrated the resolve of public sector workers and their supporters—a hundred thousand strong at one demonstration—to stand up to austerity measures and threats to public sector unions. When protesters answered the call to occupy Wall Street by encamping in Zuccotti park, they did more than occupy a park. They actualized an idea.

This idea had taken shape in the squares of Egypt, Spain, and Greece. The continuity between the forms of struggle—encampments in squares—made it possible to believe that the uprisings were not simply singular expressions of discontent. It enabled them to be read not merely as local or national political events but as instances of a global movement. That people responded to Adbusters’ call for an occupation of New York’s financial district is not accidental. They responded because the idea already made sense to them. They had already seen it in action. They believed it could work because they had seen it at work—to the point of toppling a regime—for nearly a year.

To be sure, there were initial doubts, and a lot of debate among radical and mainstream groups about whether or not this effort was going to be worth their time. No one knew whether fifty people sleeping in a New York park would become the movement they were waiting for. Once Occupy took off, though, it was clear what participation meant. It was clear because the form of Occupy had been established in advance of its arrival. Its shape was the shape of the encampments of those that had already happened in other countries. The work that people knew needed to be done was the work of proving that the movement of the squares had arrived.

This meant creating iterations of the form that was in the cultural consciousness. People demonstrated to the world and to themselves that Occupy brought the global movement to the belly of the beast, the heart of enemy territory, the citadel of global finance. And they did this by copying what others had been doing throughout the last year. The form of Occupy wasn’t created—it was given.

The availability of an easily replicable model made it easy for the movement to spread. Just as had been done in Zuccotti, people in cities and towns throughout the US and the world appropriated the now familiar signifiers: tents in a central square, cardboard signs, hand signals, the General Assembly, and the common name “Occupy.” As they reiterated the signifiers of the movement in their own specific contexts, people brought the form to life.

Consider the Illuminator. For Occupiers and their supporters, the N17 projection of an Occupy “bat signal” visible from Brooklyn Bridge was extraordinarily moving. Coming off the eviction of the park, tens of thousands of Occupiers marching on the bridge were inspired to see movement slogans projected onto the Verizon building. This action, now deeply inscribed in the collective sense of Occupy, did not result from a GA. It came about when a couple of activists realized that the ideas thrown around in an action coordination meeting were not big enough, not as unifying as they needed to be at such a crucial time for the movement.

The strength of Occupy comes from a political logic completely counter to the consensus process. Occupiers made the decision to take up the name “Occupy” not because they agreed with it, but because they knew “Occupy” represented something they believed in, something they had already seen at work. When people joined, they were joining not because of a process, but because of an idea. They were committing, in other words, not to talk to one another until they all agreed but to join a struggle together with others with whom they might not necessarily agree.

The structure of Occupy was never horizontal. It consisted of groups that had many different organizing structures operating together under a common name. Unfortunately, the rigidity of those insisting on horizontality, openness, and consensus discouraged the involvement of groups following different processes, pushing their participation outside rhetorically demarcated grounds. The theoretical champions of inclusions were in practice the most exclusive, with the result that the actions on which the movement depended for its energy could not be accounted for in the terms deemed central to the movement’s self-understanding.

The Working Families Party, MoveOn and the City Council Representatives supporting Occupy, for example, were publicly hated by many Occupiers. Many of those individuals and groups couldn’t even acknowledge that they supported the movement for fear of attack. The fact is that these groups were committed to the movement an demonstrated their solidarity in ways that remained below the radar since some would have rejected its involvement had they known about it.

No one denies that vertical organizational structures privilege some individuals, ideas, and groups over others. This is absolutely clear. And there is a benefit to this clarity—we know who’s responsible and we can make them accountable. In the absence of clarity, we end up in the miasma of horizontality—a situation of infinite deferment and deniability that entangles people in frustrating, pointless, and ultimately deceptive processes.

If not democracy then what alternative best represents a threat to contemporary global capitalism?

There is nothing about democracy that necessarily goes against capitalism. Democratic processes have been coextensive with the capitalist mode of production and accumulation. The position that represents the threat to global capitalism is the one that refuses capitalism outright and insists on universal egalitarian emancipation. This position operates above and beyond an acquiescence to capitalism given the proper deliberative process.

A large part of Occupy did in fact represent this position. The financial magazines reporting on Occupy made this very clear. Repeatedly they announced that the world was seeing the result of people giving up on democracy and taking to the streets to demand a system other than capitalism. In saying this, the financial magazines embraced a possibility more radical than that of many Occupiers. They recognized in Occupy a real alternative to capitalism, an actual counterpower.

As counterpower, it couldn’t exist alongside capitalism. It threatened capitalism. It represented a limit to an otherwise limitless system, the end of the system altogether. So even as those within the movement argued over its ideological content, those exterior to it knew what it meant.

Arguing for Occupy as counterpower means conceiving Occupy as a site of struggle within which one takes a position. Although this has not been the primary understanding of the movement offered by Occupiers, many recognize that Occupy was only as powerful as they made it. The struggle over the name was a struggle within the movement as well as a battle against forces hostile to the movement. While the encampment was ongoing, these Occupiers understood that the movement would dissolve if the police and government were successful in their efforts to shape the name and in doing so discredit it.

The power of counter-power exists in the appearance of the alignment forces. We see it in action when dots appear connected even when forces are not exactly aligned. Change becomes possible when a new way of thinking, an idea, inspires a population to stop believing in a particular narrative about the way the world works and start believing in another one. This is what Occupy offered. It was a way of doing politics that put an idea of universal egalitarian emancipation to work by copying the form in which appeared, reiterating the signs and symbols denoting it, and struggling together under a name in common.

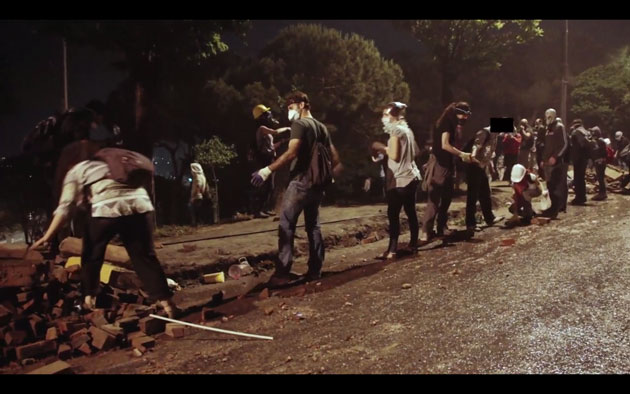

August 2013, Passing brick from person to person, Occupy Gezi, Turkey

Video stills from Global Uprisings -http://www.globaluprisings.org/

Additional research:

Not An Alternative presenting on Media, Communication, Outreach panel at Global Uprisings Conference – Amsterdam, Nov 2013′

How Do Social Movements Communicate? from Not An Alternative on Vimeo.