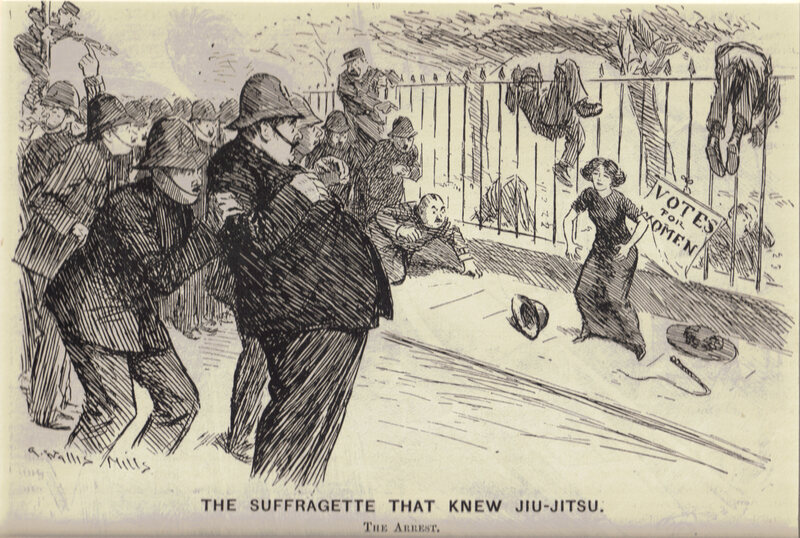

Above Photo: Famous suffragette Edith Garrud demonstrates a jujitsu move on a policeman. Tony Wolf/Public Domain.

Beneath the folds of their Victorian dresses, the jujutsuffragettes concealed wooden clubs—preparation for hand-to-hand combat with the London police.

The Indian clubs, shaped like bowling pins, were used in exercise classes of the era, flaunted in leg lunges, or alternatively, brandished against cops. When policemen heard that radical suffragettes were arming themselves, they began worrying about pistols and firearms; what they didn’t expect was to be met with an eclectic form of the Japanese martial art of jujutsu (also spelled jiujitsu or jujitsu). The women pulled out their clubs, the police pulled out their truncheons, and the sparring began.

This is a story of female armed resistance that has been little told until recently, when a studio film and a new graphic novel trilogy aim to show the harder side of British feminism.

This contingent of British women fighting—very physically—for votes was officially named the Bodyguard, but they soon earned other monickers through local papers and word-of-mouth like the Amazons and the jujutsuffragettes. They were an underground unit of the Women’s Social and Political Union, trained and organized in response to England’s Cat and Mouse Act, which was an effort to handle the hunger strikes of imprisoned suffragettes in an ethically palatable manner, officially known as the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act of 1913. The Act was the culmination of an intense propaganda war between feminists, who viewed force feeding as torture, and the government, whose response was to release protesters from jail long enough for them to recover their health before tracking them back down to rearrest and re-imprison them on the original charge.

The Suffrajistus are not here to mess around. (Image: Joao Vieira/Jet City Comics)

And that’s where the Bodyguard stepped in—in between their sisters-in-arms and members of law enforcement, their mission to keep these prison breaks as long as possible. The women of the Bodyguard were extremely fit, willing to risk their health, safety and freedom, and almost always single, since it was considered unfair for mothers to be thrown in jail. They came from the ranks of the most radical suffragettes and studied jujutsu in a network of secret locations, using codenames and whatever subterfuge necessary to keep their activity private from prying eyes.

Jujutsu, a centuries-old form of armed combat, roughly translates to the “art of yielding.” First introduced in Britain in 1898, jujutsu was considered suitable for women, even elegant and feminine. Jujutsu, unlike English wrestling, is not about overpowering someone with force; instead, you skillfully yield to your opponent’s movements and use their weight and strength in your favor. Jujutsu became a kind of metaphor for the women’s suffrage struggle, says Tony Wolf, one of the world’s top experts on archaic martial arts. Since the radical movement was small in numbers, jujutsuffragettes had to rely on skill and trickery to overpower the government.

How has a secret army of radical suffragettes defending their cause against the Man with mixed martial arts remained so unknown until now? Wolf thinks that Suffrajitsu, like many other movements of the time, was forgotten amidst the cultural chaos brought about by the First World War. The 2015 film Suffragette is the first time this movement has been highlighted in popular media, and for the past several years, Wolf and a handful of others have been doing serious research to bring this band of bodyguards back into the popular consciousness.

Who’s gonna take this chick on? (Image: Tony Wolf/Public Domain)

Who’s gonna take this chick on? (Image: Tony Wolf/Public Domain)

Suffrajitsu, released earlier this year, is a graphic novel trilogy set in 1913 and a collaboration between Tony Wolf and illustrator Joao Vieira. It’s the story of the Amazons’ efforts to protect their leaders against arrest and assault, the story of women living in an extremely patriarchal society at the height of what was almost a civil war in England. The first chapter of the trilogy is closely based on real events, while the subsequent chapters diverge into an alternate-history action-adventure story. One of the biggest challenges, says Wolf, was picking and choosing appropriate characters from real life who could have plausibly been involved in the 1913 women’s rights movement and have joined the Amazon team. All but two of the characters are fictional representations of historically real women, who he researched through reading extensive first-person diaries and accounts. Wolf sees Suffrajitsu as a compelling form of “edutainment,” and hopes especially that it will get teenage girls interested in history, martial arts and defense training.

Wolf, a native of New Zealand, grew up training in martial arts, gymnastics and fencing, and when he started looking for a career, he says he was “basically qualified to be a professional assassin.” Instead, he segued into the entertainment industry, becoming a fight choreographer for theater, film and television. Throughout this time, he was always interested in the unusual history of martial arts, especially a form known as bartitsu that incorporates jujutsu, boxing, and cane fighting, popularized by the revival of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes (where it was mislabeled “baritsu”).

Amazons secretly practice their martial arts in a scene from Suffrajitsu, the graphic novel. (Image: Joao Vieira/Jet City Comics)

A small, like-minded community began tracking down obscure newspaper and magazine articles on the subject, and Wolf volunteered to edit the first of two volumes of the Bartitsu Compendium, which led to his discovery of Suffrajitsu. Wolf has since co-directed and co-produced a documentary on bartitsu and written a biography, Edith Garrud: The Suffragette Who Knew Jujutsu. When science fiction writer Neal Stephenson asked him if he would write a graphic novel about the Bodyguard, Wolf jumped on the opportunity to get creative with a trove of themes and information he’d been involved with for so long.

Wolf describes himself as a “very staunchly feminist sort of guy,” and while writing Suffrajitsu, he approached the women as a group of professionals, political radicals committed to an ideological goal. “The fact that they were female was third or fourth in the list of priorities in terms of how I wanted to present them,” he explains. At the same time, he didn’t want it to be “women: good; men: bad.” There were many men who very assiduously supported the radical suffrage movement to the point that they earned their own nickname: suffragents. Suffragents supported these women while they engaged in very aggressive, though non-violent civil disobedience. “These women were very careful and also very lucky that no one was physically harmed in their protests—even the extreme stuff like bombing,” says Wolf.

The Bodyguard takes on the police! (Image: Joao Vieira/Jet City Comics)

The need for self defense, then and now, is a reminder of continuing power imbalances, says Wolf. In the 1980s, he taught classes in women’s self defense. “A thing I learned from my students was how very vulnerable a lot of them felt,” he says. “I recognized that a lot of women feel threatened doing things that basically guys don’t need to worry about, such as walking down to the store to get some milk. I’d sort of known that intellectually, I guess, beforehand, but working with large number of women over several years really drove that point home.” Now, if he’s walking to the convenience store at night and there’s a woman approaching in the opposite direction, he’ll cross the road to avoid making her feel uncomfortable or threatened.

This week in Chicago, Wolf is hosting an Obscura Society event to share the story of the Suffrajitsu. It is “a kind of Edwardian soirée,” he says, involving martial arts demonstrations and Q&A. The event will offer certain touches, with pictures of actual members of The Bodyguard in action, popular ragtime of the era, and subtle tributes to the purple, white and green that symbolized the radical suffragette movement.

When asked whether Suffrajitsu has a modern-day equivalent, Wolf is quick to name FEMEN, an Eastern European activist organization. “I’ve been waiting for someone to make this connection, actually,” says Wolf. “The parallels between this group and the suffragette Amazons is quite extraordinary.” FEMEN activists train similarly to the Amazons in 1913, learning self-defense techniques that make it difficult for security guards to easily remove them. They practice active resistance and tend to operate in conditions of secrecy. They’re most known for their topless protests, their basic thesis being that the only way for women’s issues to receive popular attention is for FEMEN women to go topless. Activists will wait for a large televised event to take place, and then stage a radical protest, jump over barriers, strip off their tops, and yell slogans—a reminder that the world still needs jujutsuffragettes.