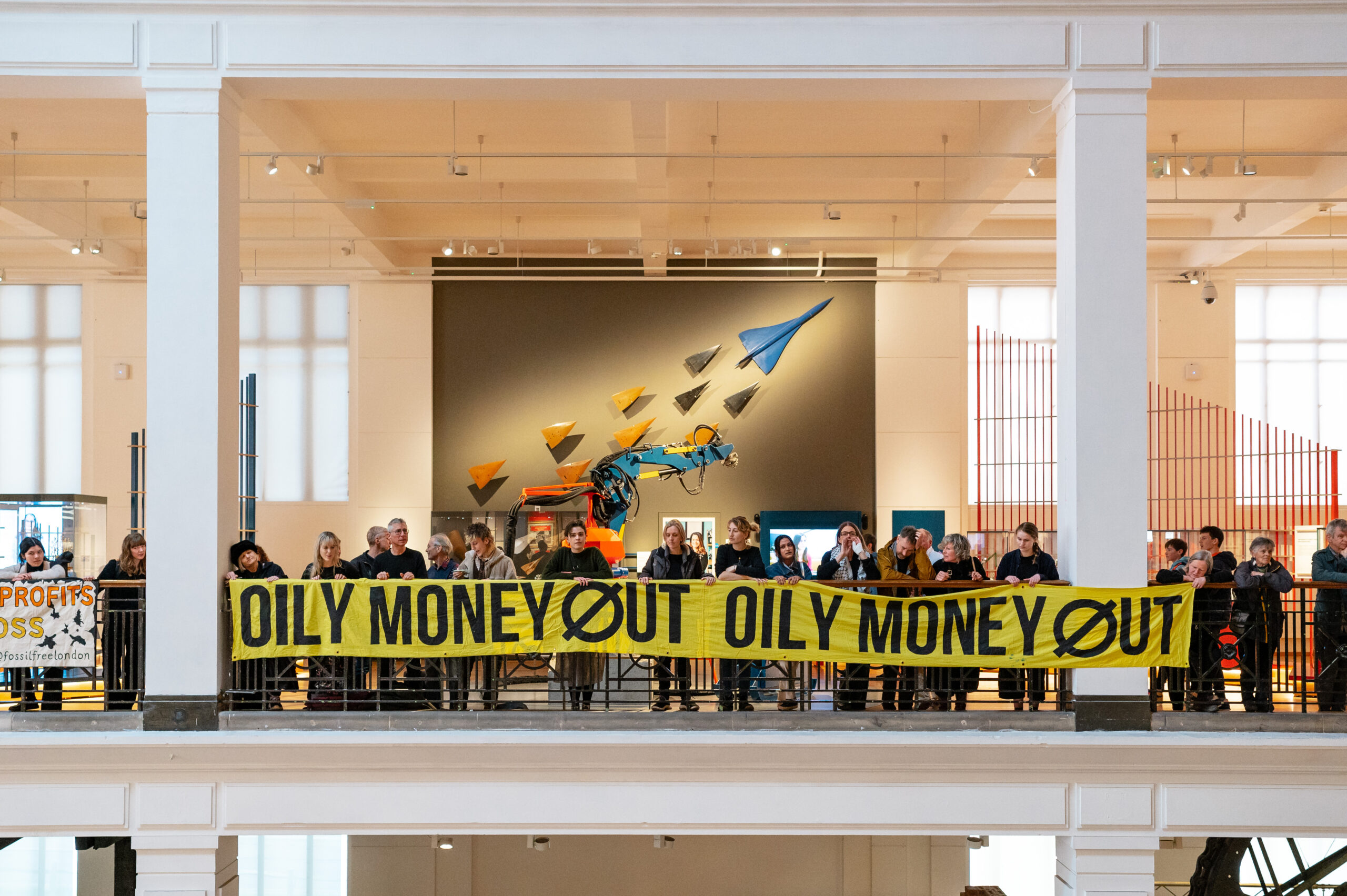

Above photo: During a 2024 protest against the Science Museum’s fossil fuel-related sponsorships, activists with the climate campaign group Extinction Rebellion unfurled a banner reading “Oily Money Out” over an interior balcony. Extinction Rebellion / Andrea Domeniconi.

Brunswick Group’s strategies aimed to neutralise growing calls for theatres, museums, and galleries to distance themselves from climate polluters.

Sadler’s Wells, a top performing arts theatre in London, hired one of the United Kingdom’s biggest public relations agencies — and one with close ties to the oil industry — to help it defend a sponsorship deal with Barclays.

Brunswick Group — whose clients have included oil giants BP, Shell, and Aramco, as well as Barclays, a major financier of fossil fuel development — drafted a May 23 letter to the Financial Times defending corporate sponsorships of the arts, and signed by Sadler’s Wells and 10 other leading UK cultural institutions, according to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests filed by campaign group Culture Unstained and shared with DeSmog.

The letter was part of broader efforts by a group of high-profile theatres, museums, and galleries scrambling to respond to protests, open letters, and artist boycotts over sponsorship deals that critics accuse of disguising corporate complicity in the climate crisis and Israeli military operations in Gaza.

“A fossil fuel PR firm, Brunswick Group, is being commissioned by a publicly funded arts institution, Sadler’s Wells, to defend the theatre’s partnership with Barclays, the UK’s biggest climate-wrecking bank, which is also named by the United Nations as complicit in the genocide of Palestinians,” said Isobel Tarr, co-director of Culture Unstained.

Sadler’s Wells income of £41.8 million for the year ending 31 March 2024, the most recent information available in the UK Register of Charities, included about £4.6 million from nine government grants.

“By drawing other arts institutions into a defensive communication strategy which Brunswick Group themselves designed and delivered, it has manufactured a polarising narrative of ‘protestors versus the arts’ which is not remotely representative of the views held across the sector,” Tarr added.

Brunswick Group said it was “proud” to support the role of corporate sponsorships in the arts.

“These partnerships facilitate the widest possible access to cultural institutions and experiences, and we were happy to help co-ordinate this letter on behalf of a number of arts institutions,” said a Brunswick Group spokesperson. “The letter was not specific to any particular sector of business but making a vital point about the crucial role corporate partnerships play in supporting the UK’s cultural institutions.”

Sadler’s Wells did not respond to a request for comment.

Arts And Culture, Arms And Oil

Between 2016 and 2021, Barclays provided £124 billion ($167 billion) in financing to the fossil fuel industry, more than any other European lender, according to analysis by Reclaim Finance. By comparison, Barclays told the Guardian in 2024 that “it had supported the UK music and arts sector with £112 million over the past 20 years” (the equivalent of $164 million in 2025).

Barclays was also among the financial institutions underwriting Israeli government bonds funding military operations in Gaza, according to a United Nations report. In September, a U.N. commission found that Israel had committed genocide against Palestinians.

Against a backdrop of growing protests urging Sadler’s Wells to cut ties with the bank, Brunswick Group began developing an 18-24 month communications strategy in November 2024, according to a Brunswick presentation to Sadler’s Wells leadership obtained through the freedom of information requests filed by Culture Unstained.

The group is part of a growing movement calling on museums, festivals, and other cultural institutions to cut funding ties with fossil fuel companies and their financiers.

Oil and gas companies use cultural sponsorships to maintain what the industry calls its “social license to operate” — enough public support to continue business as usual — despite the evidence that the industry has misled the public about climate change for decades while lobbying against climate action.

A Sadler’s Wells employee, who declined to be named for fear of professional repercussions, said Brunswick Group had drafted the May letter to the Financial Times “as though it represented the views of the organisation as a whole.

“But it does not represent the way I feel, or how a lot of staff in the organisation feel.”

The employee described an “atmosphere of silence” inside the theatre surrounding the Barclays partnership. “There has been virtually zero communication on this issue in the last two years.”

Many members of staff were angry, the employee said, that Nigel Higgins — who serves as both chairman of Barclays and chair of the Sadler’s Wells board of trustees — had been present at a staff listening session on the issue in October 2024. During the meeting, “some members of staff really spoke out and gave their thoughts. After that it was silent… It felt like a tick-box exercise to appease staff,” the employee said.

An employee of the Science Museum, who also asked to remain anonymous for fear of professional repercussions, said the letter was “universally ridiculed” by museum staff in private group chats. “It has been mentioned fairly regularly as an example of the divergence felt between workers, particularly among the lower grades, and the Science Museum’s leaders and directors,” the employee said.

The employee added that many staff remain opposed to the Science Museum’s partnerships with Indian conglomerate Adani Group, the world’s largest privately owned coal producer, and BP. BP supplies oil used by the Israeli military through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, according to the U.N. report.

Activists protested outside BP’s London headquarters ahead of its annual general meeting in April, holding banners reading “BP funds war crimes” and “Stop fuelling genocide and climate breakdown.”

“People are not really able to feel a lot of pride or joy in the work they do, because it just seems to be clouded by the really dire and unethical relationships which are sustained by the museum itself,” said the Science Museum employee.

The Science Musuem did not respond to a request for comment.

‘Dance Matters’

With more than 1,360 staff working across 27 global offices, Brunswick Group is one of the UK’s largest PR firms. Its clients include a quarter of FTSE100 companies, according to the company’s website.

Brunswick Group has worked with more than 52 oil and gas companies since 2001, according to DeSmog research, including during some of the industry’s worst crises.

After Shell admitted in 2004 to overstating its oil and gas reserves by 20 percent, it hired Brunswick Group to help defend its reputation in the ensuing scandal. Three of Shell’s top executives resigned in the wake of the revelation, which caused Shell’s shares to plunge 10 percent on the day the news was made public, and led to a $120 million fine from regulators in the United States.

In 2010, BP used Brunswick Group to help it grapple with the public backlash to the Deepwater Horizon disaster, which killed 11 and injured 17 workers, and spilled an estimated 4.9 million barrels (210 million gallons) of oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

Sadler’s Wells had faced pressure over its Barclays partnership in the years before Brunswick Group developed its communications strategy.

In 2021, a campaign led by the actor Sir Mark Rylance published an open letter calling on Sadler’s Wells to drop its Barclays sponsorship over the bank’s financing of fossil fuel extraction. The Standard reported at the time that the theatre had a deal with the bank to offer “The Barclays Dance Pass scheme, which funds £10 ($13) tickets for up to 10,000 young people aged 16 to 30 a year.”

In August 2023, five climate activists from Fossil Free London ran on stage during a ballet performance of Romeo and Juliet, unfurling a banner that read “Drop Barclays Sponsorship.” Three months later, in November, a group made up of arts industry employees called Cultural Workers Against Genocide published a letter with more than 700 signatories — including dancers, performers, writers, and artistic directors — accusing Barclays of investing in Israeli arms firms and calling for dialogue with Sadler’s Wells management.

In January 2024, protestors from Cultural Workers Against Genocide disrupted a ballet performance of Edward Scissorhands at Sadler’s Wells theatre in Islington over the theatre’s ties to Barclays.

“Our dealings with Sadler’s Wells throughout this period have been defined by total stonewalling,” said a spokesperson from Cultural Workers Against Genocide. “They have refused to meaningfully engage with us in any form, despite thousands of artists, workers and audience members calling on them to reconsider their relationship with Barclays. For two years, those voices have been ignored.”

In September 2024, more than 1,000 artists and Islington residents, including actors Maxine Peake and Juliet Stevenson, and MP Jeremy Corbyn, signed an open letter demanding the theatre end its relationship with Barclays due to the bank’s investments in companies whose weapons and military technologies have been used against Palestinians.

Two prominent Irish choreographers, Oona Doherty and Michael Keegan-Dolan, also took a stand that month against the Barclays sponsorship by leaving their positions as associate artists at Sadler’s Wells, citing the bank’s financing of fossil fuel and arms companies.

In its November 2024 presentation, Brunswick Group suggested that Sadler’s Wells adopt a core message: “Dance Matters.” The brief diagrammed several issues that Sadler’s Wells could use in public engagement, such as “culture as a driver for the economy” — language that would appear in the May 2025 Financial Times letter.

“Ethical funding”, “culture as a target for activism”, and “government culture policy” were all greyed out — marking them as issues that Sadler’s Wells should avoid.

Fresh demonstrations, organised by the campaign group Fossil Free London, erupted at the theatre group’s flagship venue in Islington just a few weeks later. During performances of the ballet Swan Lake in December and January, protestors dressed in white tutus doused themselves in fake oil while holding banners that read “Cut Ties with Barclays.”

According to emails exchanged by trustees of the National Gallery and Brunswick staff between March and May 2025, Brunswick Group drafted the letter to the Financial Times defending corporate sponsorships and helped Sadler’s Wells to recruit the 10 other major arts and culture organisations in signing on. “The idea is to find a good moment to publish this in a national title, such as the Times, with a view to landing this in May — pending signatories and the right hook,” said a 19 March email from a Brunswick Group employee to National Gallery trustee Tonya Nelson and Sadler’s Wells co-CEO Sir Alastair Spalding.

According to a 14 May Brunswick Group document forwarded to Victoria and Albert Museum Director Tristram Hunt by Sir Alistair Spalding, the publication date of the letter in Financial Times letters page was intended to mark the one-year anniversary of the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s decision to end its 20-year funding partnership with Baillie Gifford, a Scottish fund manager with investments in fossil fuels and arms manufacturers, following pressure from authors and other working in the publishing industry.

Baillie Gifford subsequently withdrew its support from several other literary festivals — moves that sent shockwaves through the culture industry by showing how vulnerable sponsorships could be to activist pressure.

Fossil Fuel’s Sponsorship Strategy

Internal fossil fuel company documents unearthed by a United States Congressional investigation, and analysed by DeSmog show that BP, Shell, and other oil and gas companies have used sponsorships explicitly to protect against “external threats” such as “the policy and politics of climate change.”

These documents underscore the role of public relations companies — which often broker such sponsorships as part of a wide range of lobbying and reputation management services on behalf of the fossil fuel industry — in delaying climate action.

At a world leaders’ meeting ahead of the COP30 climate negotiations in Brazil last month, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres warned that corporations were making record profits from climate devastation, “with billions spent on lobbying, deceiving the public and obstructing progress.”

“Fossil fuel giants keep exploiting the needs of underfunded cultural institutions to try to save their reputations, bolstered by big PR firms,” said Siân Berry, a Green Party MP. “Hard-working campaigners have already persuaded many institutions to divest from these companies, but it must now be the responsibility of Government to kick fossil fuels out of the arts with a tobacco-style ban on advertising and sponsorship.”

Amid protest actions at many prominent venues, several institutions have ended fossil fuel partnerships, among them the National Portrait Gallery, Royal Shakespeare Company, and Scottish Ballet.

The Science Museum ended a sponsorship deal with Equinor in 2024 due to the Norwegian oil giant’s failure to lower carbon emissions in line with the Paris Agreement goal of limited global warming to 1.5C — though the museum continues to receive money from BP.

In November 2025, the Museums Association — a membership organisation representing more than 7,000 individual members and 500 institutions — voted overwhelmingly in favour of a new code of ethics that recommends museums transition away from sponsorships by organisations involved with “environmental harm (including fossil fuels), human rights abuses, and other sponsorship that does not align with the values of the museum.”

DeSmog contacted the 10 additional institutions that signed the May letter organised by Brunswick Group. The British Museum responded to say: “The Museum, like our peers, benefits from a blend of public and private funding and, as a public body, has an obligation to ensure the long-term financial stability of the Museum. Both are essential for this stability and to keeping our doors open to everyone, free of charge, preserving the extraordinary collection in our care for centuries to come.”

The British Museum also referred DeSmog to a March Financial Times opinion essay in which director Nicholas Cullinan warned that the activists’ demands were forcing some organisations to scale back on programming. Cullinan raised concerns that institutions like the British Museum would have to introduce entry fees if they dropped corporate sponsorships — creating barriers to access for families with lower incomes.

“I fear that if we allow the debate to become too pious, in particular around the question of corporate sponsorship, it will be audiences, visitors and future generations who will ultimately pay the price,” Cullinan wrote. “What replaces that money? Who fills those gaps? If [protesters] have no answers, then their claim to be concerned about the future of the arts and culture will ring hollow.”

‘Risks And Reputation’

By early 2025, Arts Council England, a government body that distributes nearly £500 million of public arts funding annually, was already engaging with cultural organisations about the mounting activist pressure over sponsorships.

On 20 March, Tonya Nelson, executive director of enterprise and innovation at Arts Council England emailed Gabriele Finaldi, director of the National Gallery, to ask if he wanted to sign the letter drafted by Brunswick Group. “As you know, many arts and culture organisations are facing demands to refuse donations from corporations linked to certain political issues/events. Sadler’s Wells is leading an effort for a collective statement regarding the need to maintain corporate sponsorship” Nelson wrote, noting the British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, and National Theatre had already agreed to sign.

A spokesperson for Arts Council England said the organisation does not work with Brunswick Group, and that Nelson had shared the letter with the National Gallery in her capacity as a trustee. Arts Council England does not fund the National Gallery, the spokesperson added.

On March 24, Arts Council England hosted a “Risks and Reputation” round table at Sadler’s Wells, documents obtained via the FOIA request showed.

The meeting, chaired by Arts Council England chair and former Tate director Nicholas Serota, brought together leaders from 28 institutions across the UK — eight of whom would go on to sign the letter to the Financial Times two months later.

Minutes of the meeting revealed that participants discussing mounting “a bold, positive joint campaign” aimed at “raising awareness of the public value in private sector funding,” noting that “Government, and funders such as ACE [Arts Council England], endorsing this message will be both welcome and important.”

Representatives of the institutions expressed concerns over “misinformation” spread by activists, and noted that “the PR advice in general has been to avoid giving oxygen to the issues of protest and for arts organisations to stay silent in response. However, there is recognition that this simply doesn’t work in the current context, nor when organisations are dealing with the immediacy of stories being spread through social media.”

Participants in the roundtable reflected that they had “maybe made missteps in making public statements in certain areas, e.g. Black Lives Matter/Ukraine I.e. in commenting on some issues in the public domain, it has created expectations that this will be the case in other areas, such as Israel/Gaza. This has created a lack of clarity about the role and stance of the arts organisation.”

The spokesperson for Arts Council England said that the boards and leadership teams of the organisations it supports are solely responsible for the selection of additional funders and types of funding. “These decisions can be complex and challenging, especially when audiences, artists, staff or wider stakeholders have strong views about sponsorship and private giving,” the spokesperson said. “While it is for each organisation to weigh up their choices, the Arts Council believes that corporate giving and philanthropic support play an important role in the funding ecology of the cultural sector, and we support organisations that draw on this potential source of revenue. We are here to share research, to encourage open discussion, and to support leaders as they navigate these decisions,” they said.

After the March round table, Brunswick Group staff (whose names and job titles were redacted in the FOI responses) liaised directly via email with senior museum directors over the letter to the Financial Times, including the National Gallery’s Finaldi, and Science Museum Director Ian Blatchford.

The letter appeared in the Financial Times under the title, “One year on from the Baillie Gifford arts sponsorship boycott.” It argued that “[O]ur museums, theatres, festivals and artists need to operate within the economic structures in which society operates…we must find a way to show that cultural organisations contribute to a better world, and partnership with business and philanthropy is an admirable and valuable part of that mission.”

The letter referenced Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy’s warning in a February 2025 speech that “moral puritanism” towards corporate funding risks “killing off” arts and culture.

Nandy’s Department for Media, Culture and Sport funds several of the letter’s signatories, including the British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, National Gallery, and Science Museum Group. (Arts Council England does not fund the National Gallery, British Museum, or Victoria and Albert Museum).

From Oil Rigs To Old Masters

Beyond Brunswick Group’s extensive work for oil and gas clients, senior staff at the firm also have a network of ties to the arts industry.

Caroline Daniel, a partner at Brunswick Group, sits on the board of the Baillie Gifford Prize. Daniel also spent 17 years at the Financial Times, according to her profile on Brunswick Group’s website, including six as editor of the FT Weekend, which carries the majority of the paper’s coverage of arts and culture.

At least three Brunswick Group executives have held board positions at institutions that signed the letter to the Financial Times, and Brunswick Group has provided consulting services to at least four of the signatories.

David Lasserson heads Brunswick Arts, a division specializing in public relations, reputation management, and “maximising sponsorship” of arts and culture organizations, according to the company’s website. Lasserson has worked with the British Museum, the National Theatre, and the Southbank Centre, an arts venue in London, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Charlotte Sidwell, a director at Brunswick Group, has worked with the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, according to her employee profile on Brunswick Group’s website, as well as the East Bank — a cultural hub that opened in Stratford in January this year that is home to Sadler’s Wells’ new 550-seat theatre. Vice-President Louise Charlton, who co-founded Brunswick Group in 1987, is a trustee of the National Theatre.

Susan Gilchrist, Brunswick Group’s chair of global clients, is a former chair of the Southbank Centre, and also served as a trustee of London’s Old Vic theatre.

Patrick Handley co-heads Brunswick’s Energy and Resources team, which works directly with oil and gas clients. According to Handley’s LinkedIn profile, his clients include BP — Handley led Brunswick Group’s London crisis communications for BP during the Deepwater Horizon disaster, according to the Telegraph. He “often works with Brunswick Arts on prominent theatre, museum and art gallery assignments,” according to the firm’s website.

“The revelation that Sadler’s Wells has now turned to Brunswick, a PR firm known for rehabilitating the public image of fossil fuel giants like BP, is sadly not surprising. What is shocking is hearing a publicly funded arts institution adopt the same crisis-communications playbook and corporate language as Barclays and BP,” said the spokesperson for Cultural Workers Against Genocide.

“At this point,” they said, “we must ask ourselves, when did our cultural spaces stop being publicly held places of collective imagination, solidarity and courage, and become corporate vehicles defending the interests of financiers implicated in mass violence?”

CORRECTION (17/12/25): The original version of this article stated that the Edinburgh International Festival had ended a funding partnership with Baillie Gifford. The correct organization is the Edinburgh International Book Festival.