Despite private and public requests for diplomatic assistance for the WikiLeaks publisher, Canberra’s policy — shown by FOI documents — has been one of complicit inactivity in the face of his persecution.

The significance of the Belmarsh Tribunal could not be greater, and not only for Julian Assange and his family. We have reached a critical point in history for press freedom, and for all human rights intertwined with it.

Julian Assange once said:

I understood this a few years ago. And my view became that we should understand that Australia is part of the United States. It is part of this English-speaking Christian empire, the centre of gravity of which is the United States, the second centre of which is the United Kingdom, and Australia is a suburb in that arrangement.

And therefore we shouldn’t go, ‘It’s completely hopeless, its completely lost. Australian sovereignty, we are never going to get that back. We can’t control the big regulatory structure which we’re involved in in terms of strategic alliances, mass surveillance, and so on.’

No, we just have to understand that our capital is Washington. The capital of Australia is D.C. That’s the reality. So when you’re engaging in campaigns, just engage directly with D.C., because that’s where the decisions are made.

And that’s what I do, and that’s what WikiLeaks does. We engage directly with D.C. We engage directly with Washington, and that’s what Australians should do.

Julian’s proposition is validated by the Freedom of Information documents I’ve obtained and examined over almost a decade. They tell a story – not the whole story – of institutionalised prejudgment, “perceived” rather than “actual” risks and complicity through silence.

We all see the disparity between what governments say and what they actually do. My inference from the records is that our government’s real policy is complicit inactivity in the face of Julian’s persecution.

Gillard’s Accusation

Former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard started the ball rolling after WikiLeaks released the U.S. diplomatic cables in March 2010 by undermining the presumption of innocence and pre-emptively accusing Julian of being “guilty of illegality.”

A Whole of Government Taskforce was established and the attorney-general referred the matter to the Australian Federal Police but they found no evidence of any crime where Australia would have jurisdiction. Even so, we had further contact with the U.S.

A March 2012 cable from Washington to Canberra, titled: “US: Australian-American Relations a snapshot” related to Julian was produced but redacted — because the material included in the document “would, or could reasonably be expected to, damage Australia’s relations with the U.S.” The title of that document is a beacon guiding the entire correspondence.

In 2012 the Australian government tried to find out whether a sealed indictment existed against Julian. Our embassy in Washington approached U.S. authorities asking about U.S. legal processes and whether they intended to seek Julian’s extradition. That “request from the suburbs” went unanswered by “the centre.” U.S. officials declined to provide advice relying on the secrecy around Grand Jury processes.

Less than two months later then Attorney-General Nicola Roxon, meeting with Julian’s lawyer, Jennifer Robinson, said there “may be some things we can do diplomatically” when asked about protecting Julian. But she afterwards wrote to Jen Robinson saying Australia would not be seeking to involve itself in any international exchanges about his future. And that’s what happened.

Roxon’s correspondence was an effective Declaration of Abandonment and triggered Julian’s decision to seek asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in London in June 2012, but private and public requests for Australian diplomatic assistance continued.

In January 2019, Julian told visiting consular officials of his difficult situation in the Ecuadorian embassy and of C.I.A. involvement, and made clear that his personal situation needed to be addressed by them through diplomatic channels. The department officials were informed — but, as with so many lost opportunities in this case, nothing was done.

On July 1, 2021, the United States head of mission for Australia, Arthur Sinodinis, cabled Canberra confirming he had met with Julian’s family on June 30, 2021, and noted that:

“They outlined defects and irregularities with the legal proceedings. They are no longer interested in consular help from the Australian Government, they want diplomatic and political interventions.”

They got neither.

Returning to 2012, once Julian sought and was granted asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy there was a sense of relief that he was temporarily safe. He kept working with WikiLeaks notwithstanding his relentless public persecution by media. From the Australian government’s perspective things were in a holding pattern, conveniently leaving it out of the limelight while matters were being thrashed out between the Swedish, U.K. and U.S. governments.

While this was going on the contrasting extent of the government’s “concerted campaign of advocacy” in the case of Australian journalist Peter Greste was not lost on those following Julian’s case. (A similar unease about disparate treatment followed widely publicized government involvement later in bringing home James Ricketson and Kylie Moore-Gilbert.)

UN Finding of Arbitrary Detention

But what prompted me to resume FOI work was when the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) found in February 2016 that Julian had been arbitrarily detained and that he had not been afforded the guaranteed international norms of due process or a fair trial. (The opinions of the Working Group are legally binding to the extent that they are based on binding international human rights law.)

Then Foreign Minister Julie Bishop confirmed that she had read the report. She sought legal advice from her own department. The advice was emailed to the Attorney General’s office on Feb. 9, 2016. What that advice said has never been revealed, but at that time the Australian government could have ended Julian’s suffering by using the U.N. decision to extend diplomatic protection.

Instead, Bishop signed off on a Ministerial Submission on Feb. 12, 2016, which recommended not to seek to “resolve” Julian’s case because they were “unable to intervene in the due process of another country’s court proceedings or legal matters, and we have full confidence in the UK and Swedish judicial systems.”

After a series of exchanges with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) about the government and/or the department recognizing the legitimacy and independence of the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, DFAT finally confirmed in June 2018 that the government was “committed to engaging in good faith with the United Nations Human Rights Council and its mechanisms, including the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.” But again, nothing was done.

Abnegation of responsibility for making decisions about his fate filters through all of the Australian Government’s actions and failures to act. They obviously would rather have another government make the decision because the only proper course would involve them saying no to the U.S.

Events in 2019 really cemented the Australian government’s role as a silent collaborator.

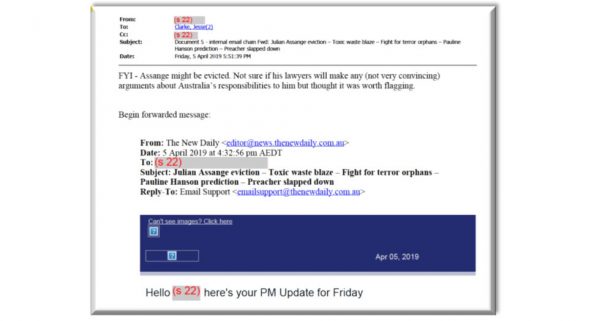

On April 5, 2019, six days before Julian was forcibly removed from the Ecuadorian embassy and arrested, an internal email from the Attorney-General’s department noted with suspicious prescience: “FYI – Assange might be evicted. Not sure if his lawyers will make any (not very convincing) arguments about Australia’s responsibilities to him but thought it was worth flagging.”

On April 11, 2019, the day of Assange’s arrest, the first U.S. indictment against him was unsealed. Consular officers were at the initial hearing on April 11 and visited Assange at Belmarsh Prison the next day. The consular report on the hearing omits the judge’s statement: “You are a narcissist who cannot get beyond his own self-interest. I convict you for bail violation.”

From when he arrived at HMP Belmarsh Julian remained on a care planning process for prisoners identified as being at risk of suicide or self-harm. He also needed urgent dental treatment.

Immediately after his arrest, with Julian being held in isolation alone for 23 hours per day, his London lawyers desperately tried to contact the Australian High Commission. The embassy did not respond to telephone calls and emails until April 18, 2019, when the High Commission sent his lawyers a letter confirming that they’d raised his dental issues with prison authorities and were still waiting to hear about the whereabouts of Julian’s belongings from the embassy.

The politics involved — predominantly of the U.S. in securing the revocation of his Ecuadorian passport, and then predominantly of of the U.K. in securing his eviction from the embassy — are stories in themselves of state action achieving goals in Julian’s individual case. Where there’s a will there’s a way.

Consular officers who visited Julian again on May 17, 2019, reported him saying he was concerned about surviving the current process and feared that he would die if taken to the United States. They noted he had lost weight and him saying he wasn’t able to eat much. The day after Julian was admitted to the health care wing because of self-harm and suicide risks. Still nothing happened.

Grave Health Concerns

Only after WikiLeaks released a statement on May 30, 2019, announcing grave concerns about Julian’s health did Canberra cable London requesting that officials contact Belmarsh about the veracity of the report and an update on his condition.

Coincidentally the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture Nils Melzer released his report the next day, confirming that Assange was suffering psychological torture. Misreporting about what Melzer said about the Australian government’s role prompted a DFAT statement on May 31, 2019, lashing out at the special rapporteur and saying the Australian government was confident that Julian was being treated appropriately in Belmarsh Prison. As with any consular client, they said, they would continue to visit Julian in prison, monitor and advocate for his health, welfare and equitable treatment, and closely follow his proceedings.

Contrary to that assertion, the Australian High Commission was writing to the U.K. Ministry of Justice a week later seeking help in getting a response from Belmarsh after they had written on three separate occasions and left messages enquiring about Julian’s welfare. And again, to the contrary, the high commissioner, George Brandis, did not try to intervene after media reports about grave concerns for Julian’s health.

The former foreign minister, Marise Payne, admitted in Senate Estimates in February 2022 to having read at least part of the Melzer Report. Notwithstanding Melzer’s concerns about breaches of due process by U.K. authorities, once again the Australian government did nothing.

Melzer issued a further statement on Nov. 1, 2019, expressing alarm that Julian’s life was at risk. He warned that his pattern of symptoms can quickly develop into a life threatening situation involving cardiovascular or nervous collapse. This was published on the ABC online news site. It should have come as no surprise to the Australian government that Julian suffered a ministroke in October 2021, on the first day of a U.S. government appeal against a ruling blocking his removal.

The Australian High Commission finally heard from the Ministry of Justice on June 15, 2019, that Julian — who at the time was on suicide watch — had withdrawn consent for HMP Belmarsh to provide medical treatment information to consular officials.

That did not mean he was refusing consular assistance or blocking visits from consular officials.

His lawyer, Gareth Peirce, wrote to the Australian High Commission on Oct. 24, 2019, explaining why Julian withdrew his consent to provide medical-treatment information and had not responded to offers of consular visits. She said he was in shockingly poor condition, that every professional warning to the prison had been ignored and she offered to meet with officials if they could help avoid the impending crisis.

Our consular officials failed to document that Julian couldn’t say his name and date of birth on the first day of the extradition hearing on Oct. 21, 2019. Why no report on obvious signs of deteriorating physical and mental health?

His co-prisoners, not consular officials, eventually successfully petitioned for Julian’s release from solitary confinement.

On Nov. 1, 2019 — the last documented personal visit from Australian consular officials, and after the purported withdrawal of consent — consular officials visited him. They recorded in detail his concerns about false reports that he had rejected offers of consular visits, that his mind was shutting down and he was dying, of difficulties thinking and lack of basic materials for preparing his defence. But yet again, nothing happened.

Julian’s lawyer, Gareth Peirce, confirmed early in 2020 that he had only been allowed two hours with his legal team since appearing in court and that Belmarsh Prison had been obstructing access. There were further reports that he had been handcuffed 11 times, stripped naked twice, and had his case files confiscated after the first day of his extradition hearing.

On Oct. 1, 2020, the last day of that hearing, Australian officials contacted Belmarsh to discuss his health and well-being. Their excuse for failing to provide consular assistance on other occasions was lacking his authority to do so.

Now, compare that history to their earlier official assertion that they would “continue to visit Julian in prison, monitor and advocate for his health, welfare and equitable treatment, and closely follow his legal proceedings.”

Spying on Embassy

During the same period the ABC reported that Julian and his lawyers were spied on in Ecuador’s embassy, and that legally privileged information and conversations were reported back to the U.S. I haven’t seen any documents and we haven’t been told what, if anything, the Australian government knew or did about the unlawful surveillance of one of its citizens, his Australian lawyers and its own consular officials.

Foreign Minister Marise Payne said she raised Australia’s expectations about Julian’s treatment with former British Secretary Dominic Raab on Feb. 6, 2020, but an FOI request didn’t turn up any documents so one must assume it was oral discussions. She then met with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at AUSMIN. FOI documents requested about that meeting were redacted in full.

In November 2020 Labor opposition senators voted with the Greens to pass a motion acknowledging many of the extraordinary factual circumstances and irregularities in Julian’s case. Our current foreign minister, Penny Wong, was leader of the opposition in the Senate at that time.

After the U.K. court decision refusing extradition in January 2021, Marise Payne released a statement acknowledging the decision’s grounds of Julian’s mental health and consequent suicide risk. Again it was noted that Australia was not a party to the case and would continue to respect the ongoing legal processes.

In June 2021, she confirmed to Senate Estimates that she had read the court decision in parts. The judgment was an agonising read in terms of Julian’s health and well-being, but neither she nor the government did anything. The Morrison government made no request that U.S. President Donald Trump pardon or not extradite Julian.

Marise Payne met with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in May 2021. Again FOI documents were redacted in full so we don’t know whether or to what extent Julian’s case was discussed.

June 2021 brought the revelation that one of the main U.S. witnesses in Julian’s extradition case admitted he had made false claims against Julian in exchange for immunity from prosecution. Media reporting on the subject appears on DFAT files, so they were and are aware of it. However, as had become usual, nothing happened.

September 2021 revealed the C.I.A. plot to kidnap or assassinate Julian. When you’re in the sights of the United States government all options are on the table.

Even though Marise Payne admitted being aware of the media report, she did not raise it with her U.S. counterpart. What we don’t know is whether Australian intelligence knew about the C.I.A.’s plans by reason of our involvement in Five Eyes, or whether that information was withheld from the minister.

The only entry of note in Julian’s 2017 consular file is a classified cable on June 1, 2017, and a redacted letter from an AFP “Federal Agent liaison officer – London International Operations,” which may or may not be relevant. Not one mainstream journalist in the country examined what our government or its intelligence agencies knew at the time about a foreign power’s plan to murder an Australian national and journalist. Again, nothing happened.

On Nov. 9, 2021, Senator Janet Rice asked in Senate Estimates: “So you think that’s all the appropriate assistance that you should have provided?” Payne simply said “I have provided the assistance that I am able to.” One wonders what was constraining her ability to provide assistance.

The ‘Glaring Absentee’

When you look at this history on the background of all that happened what we do know is concerning, but what’s being kept from us is disconcerting. Nils Melzer has a valid point when he labels Australia the “glaring absentee.”

We’ve now had a new Labor government for nine months and Julian’s circumstances haven’t changed. We’ve moved to “quiet diplomacy,” “enough is enough” and assurances that Julian’s case has been raised “at the appropriate levels” with the United Kingdom and United States — but no specifics are given, not even to his family.

The Australian government is willing to say publicly that Julian is entitled to due process. When asked, it is much less willing to say whether it believes Julian has been afforded it, even though the government’s role is to seek to ensure that due process is followed in all foreign legal proceedings against our nationals.

From an FOI point of view there’s no paper-trail to demonstrate that ministers are rigorously pushing the case with their U.S. counterparts.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong makes the point that “not all representations are made by way of letter.” I make the counterpoint that in the David Hicks case, the only remotely comparable case I know of, there was an internal paper-trail demonstrating directions being given to the U.S. ambassador, notes about ministers calling their counterparts and the prime minister standing alongside both the president and vice president of the United States at press conferences and being willing to confirm that the case had been discussed.

An FOI request produced Foreign Minister Wong’s 2022 AUSMIN “Visit to the U.S. bilateral pack” document which mentions Julian’s case. On another request all information about the prime minister meeting Julian’s family has been redacted as “relating to an international matter that is the subject of sensitive diplomatic relations involving Australia, the UK and the U.S.”

The FOI material I have obtained, including all its redactions, is telling me that Julian is a political prisoner, that this is a political prosecution, that there has not been and can be no expectation of due process, and that our government’s policy in dealing with his life is dictated by international policy considerations rather than objective considerations of truth, justice and actual circumstances. The result is that Julian remains effectively on death row.

Prime ministers apparently must resist any pressure or advice against taking strong political and diplomatic involvement in Julian’s case because of some unspecified “risk to our strategic interests.”

Anthony Albanese says he is a prime minister for and of the people — and Julian Assange is one of those people who has the support of millions of people all over the world, including in the U.S. The case propounded and stance taken by the U.S., with the complicity of the U,K. and Australia, are far removed from any sense of justice.

This is a story of institutionalised prejudgment, “perceived” rather than “actual” risks and complicity through silence. The inference from the records I’ve examined is that our government’s real policy on Julian’s persecution is complicit inactivity in deferring to the U.S.: inaction is the policy.

Individuals direct a State. For every reasonable request that has been ignored, for chairs that have remained empty when they required the presence of active observers, for every international law finding ignored, for every record that remains uncorrected, for turning away when an Australian life has been threatened, and for the silence that has descended in the face of injustice, many of the senior public servants and ministers across many departments have no shame now, but history will hold them accountable.

Dealing with Julian’s “case” — his very life — through the prism of international policy considerations and strategic alliances rather than objective considerations of truth, justice and actual circumstances is what the FOI documents suggest, and it’s a continuing institutionalised mistake.

A primary precept of good government is justice for its citizens, but because our government has ignored every injustice in his case, injustice now threatens us all with a precedent whereby the U.S. can seek to capture by any means, incarcerate and extradite anyone, including journalists or publishers, of any nationality from most places in the world, for disclosing shockingly reprehensible U.S. secrets.

By courageously publishing the truth, Julian terrified with the threat of personal responsibility and accountability those who had been operating beyond reach. He knew they’d come for him, we knew they’d come for him and they did. It’s not a hard story to understand.

Julian is a moral innovator. He made moral gains which had an immense effect on human life. He did what lay in his power to make people less cruel to others and was rewarded with nothing but personal pain. Posterity will pay Julian the highest honour for putting into the world the things that we most value: truth, transparency and justice.

History will look back on Assange as a particularly important person, and on his persecution — the details of which will be further filled out over time, and preserved forever — as an appalling politico-legal abomination.

Harking back to Julian’s own observations about the real international hierarchy, “Mr Albanese Goes to Washington” could and should be a story of an Australian prime minister quietly but resolutely standing up for truth and fairness and the rights of a citizen — and securing the release of a person who, far from being a criminal, has put his life on the line for those same values for the benefit of people the world over.