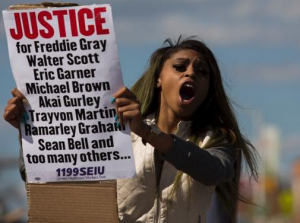

The Justice Department began investigating the Baltimore force after Freddie Gray’s death in April 2015. Its report last August found that officers routinely stopped large numbers of people in poor, black neighborhoods for dubious reasons and unlawfully arrested residents merely for speaking out in ways police deemed disrespectful.

A mural in Baltimore depicts Freddie Gray, who died in custody of Baltimore Police officers following a “rough ride” in a police van.

The report and agreement approved Thursday acknowledged what many residents, particularly those living in economically depressed areas, had known for years: “Zero-tolerance” policing — a strategy employed under then-Mayor Martin O’Malley in the 1990s to reduce crime but that instead resulted in thousands of arrests without cause — had a profound and lingering effect on the police department’s culture, and the city’s residents were still enduring the consequences.

“There are a lot of police who have been around for a long time, and they need to understand that they cannot do what they used to do,” said Tessa Hill-Aston, the president of the Baltimore branch of the NAACP.

Vanita Gupta, the head of the Justice Department’s civil rights division, said the agreement will make the city safer for everyone, including officers.

“The city and BPD will implement comprehensive reforms to end the legacy of Baltimore’s zero-tolerance policing,” she said. “And in its place, Baltimore is empowering officers to engage in proactive, community-oriented policing.”

The Justice Department agreement mandates changes in the most fundamental aspects of police work. Known as a consent decree, it is the culmination of months of negotiations and is meant to correct constitutional violations identified in the report released last year.

U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch said at a news conference Thursday that the agreement will help “heal the tension in the relationship between the Baltimore Police Department and the community that it serves.”

A hearing will allow for public comment on the agreement before it’s approved by the judge.

The agreement discourages the arrests of citizens for “quality-of-life offenses” such as loitering, littering or minor traffic violations. It also requires a supervisor to sign off on requests to take someone into custody for a minor infraction.

It mandates basic training for making stops and searches. It also commands officers to use de-escalation techniques, thoroughly investigate sexual assault claims and send specially trained units to distress calls involving people with mental illness.

Police will not be able to stop someone just because the person is in a high-crime area, or just because the person is trying to avoid contact with an officer, according to the document.

The agreement also lays out policies for transporting prisoners like Gray. Officers will be required to buckle them in with seat belts and check on them regularly.

Police Commissioner Kevin Davis said Baltimore has been “preparing for this moment for a year and a half,” and promised his officers that they, too, will benefit from the reforms.

Baltimore continues to struggle with a high homicide rate. Last year, the city recorded 318 homicides, the second-highest rate in 40 years.

The highest was in 2015, when Gray’s death and the civil unrest that followed prompted a spike that refused to relent. The city saw 344 homicides that year. With six officers being charged in Gray’s death, residents at the time accused officers of stepping back from enforcement in the city’s most violent areas. Three of the officers were acquitted, and charges against the others were dropped.

“There is a conversation about whether or not the crime fight and a consent decree reform effort can exist at the same time,” Davis said. “Of course, it can exist. I have no doubt that when we eventually emerge from this consent decree, we will be better crime fighters and have a greater, more respectful and trustful relationship with our community.”

The Justice Department in the Obama administration has launched about two dozen wide-ranging investigations of police agencies, including Chicago, Cleveland and Ferguson, Missouri, and is enforcing consent decrees with many of them. Lynch was expected to announce the findings Friday of the investigation into the Chicago Police Department.

Federal oversight under consent decrees can be long-running. Court enforcement of the agreement involving the Detroit Police Department ended last March, 13 years after it began. In Los Angeles, a judge signed an order in 2013, ending oversight that began in 2001.

“There’s a lot required of the city of Baltimore and the Baltimore Police Department that’s going to be a lengthy and expensive change for the department,” said University of South Carolina criminologist Geoffrey Alpert, adding that the Baltimore decree is particularly thorough in its supervision and oversight requirements. “It certainly looks like they’ve hit all the buttons.”

___

Associated Press writer David Dishneau contributed to this report.