Above photo: Via SDSN.

The Poor People’s Pandemic Report takes a hard look at the intersections between COVID-19, poverty and race in the United States.

Soon after the first pandemic wave subsided, COVID-19 turned from the “great equalizer” to a poor people’s pandemic in the United States, shows a recent report published by the Poor People’s Campaign (PPC). The report brings a detailed analysis of how the pandemic affected poor and low income communities in the US, asking if their experiences are being taken into consideration at all, regardless of whether we are looking at pandemic response or post-pandemic re-building.

The Poor People’s Pandemic Report is focused on the data and lived experience of people in the 1,000 poorest counties in the US, shining a light on the intersections between poverty and the pandemic. Some of the counties highlighted in the report have a very small population, which means they are not included in the official Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports. Yet, according to Shailly Gupta Barnes, policy director at the Kairos Center, it’s impossible to do a fair assessment of the pandemic if we disregard their experience. “The overall number of deaths in such counties might be smaller than in larger cities, but the effects of the deaths are magnified, and it should be equally important to consider them when we are thinking about rebuilding after the pandemic,” says Barnes.

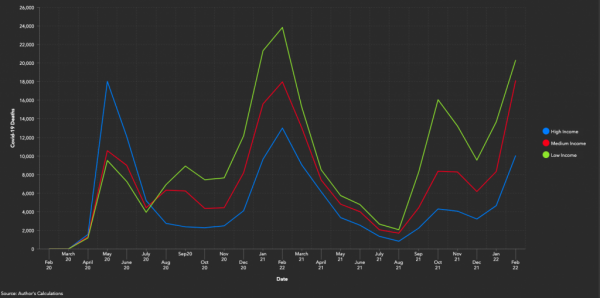

Twice the death rate of high-income communities

The death rate in many small and poor communities was multiple times larger than in other communities. In general, their death rate was twice that in high income counties, but in many cases it went beyond that. For example, Galax, Virginia, has twice the death rate of the Bronx – one of the places with the highest 10% of death rates in the US overall. Particularly devastating were the COVID-19 waves in the winter of 2020 and during the Omicron phase, when the death rate in poor countries was around 4.5 times and 3 times higher, respectively, in comparison to high income communities.

Among the places analyzed in the report, there is also a large number of counties with a predominant Black, Hispanic and Indigenous population, showing the unequal effects of the pandemic on different racial and ethnic communities. According to the PPC, counties with more than 13.4% Black residents had a significantly higher COVID-19 death rate compared to counties with fewer Black residents. “Collectively, the group of counties with larger Black communities experienced 32 more deaths per 100,000 than counties that were not predominantly Black,” says the report.

The effects of the pandemic on Black, Hispanic and Indigenous communities do not stop at the higher death rates: they also recorded a higher infection rate, likely because most of the community members work as essential workers and remained exposed to the virus. Black adults were also more likely to die of non-COVID-19 related causes as they faced barriers in accessing healthcare.

Counties where poverty and race most intersected with the pandemic are predominantly located in the southeast and southwest of the US: 76% of counties with the highest percentage of people living in poverty are located in these regions. One of these – Hinds County, Mississippi – had a COVID-19 death rate of 320 deaths per 100,000 compared to 295 deaths per 100,000 in the US in general. High death rates also occurred in poor communities outside the South, albeit in fewer instances. In the Bronx, New York, home to almost 1.5 million people – 50% of whom are poor and 10% of whom have no access to health insurance – the death rate was 538 deaths per 100,000. Dr. Jim Fairbanks, a resident of the Bronx, said to PPC researchers that this was because the people living in the neighborhood “are the essential workers who were servicing the rest of Manhattan and the city’s wealthy.”

Policy rollback

At the same time, many people in low income occupations became unemployed during the pandemic. This is particularly true for Black and Hispanic women: there was a 13% and 17% drop in full-time employment, respectively, in these two groups. As a result, policies introduced to support those whose livelihoods were put at risk during COVID-19 were of extreme importance. Expansions of healthcare rights, the moratorium on evictions, and the Child Tax Credit expansion were among the measures that helped partially alleviate economic insecurity for the poor and low-income. But, as these are now rolled back, short-term achievements are quickly disappearing.

“In the very first month of the Child Tax Credit expansion, there was already a significant drop in the child poverty rate. Within 6 months, the number of children living below the poverty line was down by 4 million. Black, Latino, and Indigenous children, who are disproportionately affected by poverty overall, had particular benefit from this policy. But as soon as the payments ended after December 2021, there was an immediate return to pre-pandemic conditions: 3.7 million children fell back below the poverty line,” says Shailly Gupta Barnes.

Rebuilding after the pandemic cannot be based on dispossessing even more those who were poor long before COVID-19 and who have faced its worst consequences, states the report. But to make sure that our pandemic recovery is on track to meet their needs, we need to take a much more careful look at the pandemic experiences of poor communities. “It’s important that we know what has been going on in these counties, so we can start building relationships and power among the communities,” concluded Barnes.

Read more articles from the latest edition of the People’s Health Dispatch and subscribe to the newsletter here.