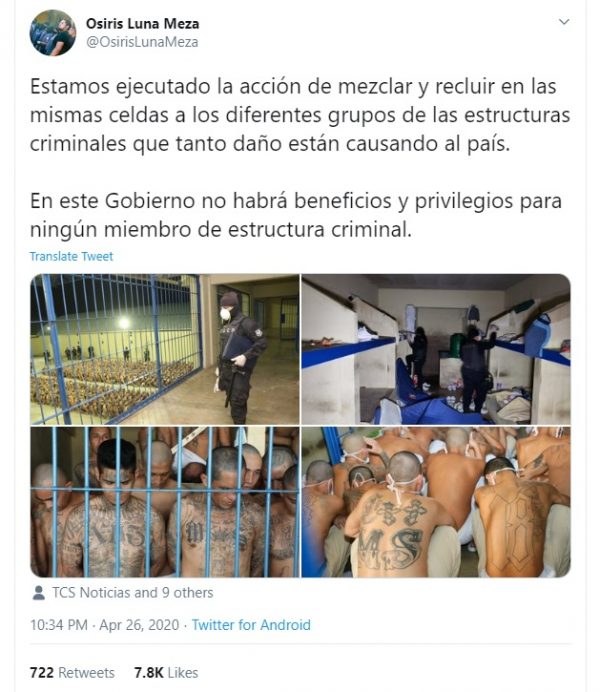

Above photo: Twitter account of Osiris Luna Meza, Deputy Minister of Justice and Director General Ad Honorem of the Penitentiary System.

Behind that jovial image of a president who takes selfies at the U.N. and governs over social media stands a strategic ally of the United States who has little regard for human rights.

The social media presence of Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele has transcended his country’s borders on at least four occasions in recent weeks. The first was when he used the armed forces to militarize the national legislature; the second was a speech in which he announced measures he was taking to confront the Coronavirus pandemic, suggesting that his government’s response would be “an exemplary model” for handling the health crisis;[1] the third was when his name and statements about “the use of lethal force” against criminals accompanied images of prison inmates in their underwear, sitting on the floor, crowded together in rows, with a heavy military presence standing over them; and the fourth was when he spoke to René, lead singer of the Puerto Rican rap group Calle 13, whose relevance will be discussed in a moment.

These four events caused confusion among certain segments of the population, including some moderately progressive ones. And for those who are far removed from the situation in El Salvador or are deprived of real information by the media blockade against that Central American nation, the links between these events may seem contradictory or senseless. But they make complete sense. Bukele is much more than those four stellar examples, and that is where I would like to begin.

Bukele served as mayor of both Nuevo Cuscatlán and of San Salvador as a member of the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN), but in October of 2017 he was expelled from the party for “promoting internal divisions and defaming the political party.” He was also accused of physically and verbally attacking Council Member Xochitl Marchelli during a session of the San Salvador City Council.[2]

Bukele’s radical turn to the right

Once he was out of the FMLN, the right-wing ARENA party blocked his presidential ambitions through its electoral infrastructure. Bukele was also prevented from participating in the primary race of his Nuevas Ideas party, which had been created out of thin air for his presidential ambitions. So he then joined the Center-right GANA Party (Gran Alianza por la Unidad Nacional). This was the vehicle that allowed him to win the presidential election against the FMLN, which had been worn down by radical economic reforms that could not be fully enacted, as well as an unrelenting media campaign against the party during its two presidential terms. There was also the problem that the FMLN had made great strides in health and education for the most vulnerable population, but was unable to win over the new generation too young to remember the civil war that ended with the Chapultepec Accords of January 1992, when Nayib Bukele was just 10 years old. But the youth were won over by the discourse and youthful image of someone who portrays himself as an outsider and not a politician.

The results of the 2019 presidential election were irrefutable: Bukele won 53.1% of the 2,701,992 votes cast, posing a tremendous challenge to the FMLN and the Left. The historic revolutionary party came in a distant third place with just 14.41% of the vote. It was clear that Salvadorans were looking for “a change,” whether or not they knew which direction it was going, and they said so very clearly.

It did not take long for Bukele to show who his geopolitical friends and enemies are. He had already revealed this before arriving at the National Palace.

Close friend of Donald Trump and the Right in the Americas

Bukele is the son of a multi-million-dollar business owner, and although his paternal grandparents are Palestinian, he had already expressed his ideological and political affinity with the government of Israel while he was mayor.[3] As President he has expelled the Venezuelan diplomatic staff from the country, and at the Organization of American States (OAS) he supported the failed attempt to invoke the Inter-American Treaty of Mutual Assistance (Río Treaty) against the Bolivarian government.

The President never hid the fact that bilateral relations with the United States were the priority. He met with Donald Trump (whom he called “simpatico and cool”), and he accepted an agreement that was framed as a tool to fight organized crime, reduce illegal drug trafficking and human trafficking, and to strengthen border security. The agreement, however,.included the designation of El Salvador as “a safe third country” for Central American migrants seeking asylum in the United States. The conservative nature of his administration and its partnership—submission, actually—to the United States also led to a visit by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to El Salvador.

Ever the pragmatist, Bukele made a State visit to the People’s Republic of China and is currently collaborating with the Mexican government to foster economic cooperation and development in the Northern Triangle of Central America. These political chess moves do not contradict his undoing of the alliances the FMLN administrations had established with the progressive governments of Latin America.

Using the military to pressure the National Assembly

Domestically, Bukele’s political practices have raised all kinds of red flags on more than one occasion.

He instructs government staffers in their daily activities by governing through social media. Donning a baseball cap worn backwards, the self-proclaimed “world’s coolest and best-looking president”[4] was the object of international scorn during this first media episode when he decided to have the military take over the National Assembly on February 9.[5]

With a military presence in the streets, Bukele arrived at the legislative chamber and, surrounded by soldiers, proceeded to pray to “pressure” lawmakers to authorize him to negotiate a US$109 million loan with the Central American Bank for Economic Integration to fund the third stage of his Territorial Control Plan.[6] The strategy seeks to militarize the country in the name of national security and resolve the crime problem with bullets, drones, and state-of-the-art technology, rather than by adequately addressing the prevailing structural inequality. As if that were not enough, there is insufficient transparency regarding the financial resources the legislature has already allocated to the plan.[7]

With a population of 6.4 million, of which 26.3%–or 1,683,200 people—are living in poverty, and 510,000 in extreme poverty,[8] Bukele has decided to implement the aforementioned Territorial Control Plan for a total cost of US$575 million by 2021.[9]

Political exploitation of COVID-19

Let’s go back to the four interlinked media episodes mentioned at the beginning of this article.

We discussed the military takeover of the National Assembly. The second episode is Bukele’s handling of the pandemic, which goes beyond his remarks that went viral on social media.

Bukele announced the “Plan for Response and Economic Relief in the Face of the National Emergency caused by COVID-19,”[10] which was extensively disseminated on social and conventional media. It established a US$300 subsidy for just over 1.5 million families and suspension of payments for such services as electricity, water, telephone, cable TV, and internet. It also announced postponement of rent and mortgage payments, and of consumer, credit card, and auto loan debts for three months. And it decreed that employers could not dismiss any employees during the time period, and were obliged to continue to pay their wages even if they were not working. The plan also opened lines of credit for micro, small, and medium-sized businesses. However, the testimony and complaints of the population began to refute the success of these measures. For example, not everyone received their $300,[11] and many of those who did not pay their bills in March, were billed late charges in April.[12]

Serious violations of human rights

But the most serious and concerning issue is that behind Bukele’s rhetoric lie multiple violations of human rights that have received scant coverage in the international press.

The Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) documented this extensively in its Special Report “Human Rights Violations Abound in El Salvador as President Bukele Responds to COVID-19.”[13]

In its report, CISPES gives details explaining how although measures were taken such as “obligatory quarantine in government-established centers for all air and land travelers returning to El Salvador,”

“… many of President Bukele’s subsequent actions have raised concerns. His more stringent measures in particular, such as military enforcement of a national stay-at-home order and arbitrary detention of people accused of violating the quarantine, have been denounced as exceeding the limits established by the Constitution of El Salvador.”

“While human rights organizations, progressive social movements, and civil society leaders in El Salvador agree that comprehensive protective and preventive measures are necessary, many are denouncing a rising tide of human rights violations stemming from the suspension of constitutional rights and use of force that has characterized the government’s response to the threat of COVID-19, as well as President Bukele’s flagrant dismissal of recent Supreme Court rulings intended to curb his detention policy.”

These complaints by human rights organizations and defenders have been growing by the day,[14] and there is no doubt that coercion has been a key feature of Bukele’s measures during the pandemic. The data confirm this. As of May 5, while the number of COVID-19 cases grew to 587, including 14 deaths, the number detained for “violating lockdown” rose to 2,394.[15] Even after the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court banned Bukele from detaining curfew violators and placing them in forced confinement or health detention, the President tweeted that he would not comply with the order: NO COURT DECISION is above the Salvadoran people’s constitutional right to life and health.”[16]

On May 5 the Legislative Assembly passed the Law on the Regulation of Isolation, Quarantine, Observation, and Surveillance for COVID-19 by a vote of 56 to 26. The law “declares the entire national territory an epidemic zone subject to health controls to fight the harm and spread of COVID-19.” Such controls include measures that continue to raise concerns about possible violations of the constitution.[17]

As if that were not enough, the conditions in which detainees are being held have caught the attention of human rights defenders. People say that once they are detained, they spend part of their confinement sleeping on the floor, and some have been held for over a month.[18]

The United Nations certifies that there have been abuses by the Bukele administration

This situation has led Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, to assert that the government of Nayib Bukele “is not respecting the fundamental principles of the rule of law.”[19]

The suspension of civil liberties peaked when Bukele first decreed a two-week state of exception on March 15, and then extended it for another two weeks on March 29, allowing it to expire on April 14. Bukele and the right-wing legislators, without the backing of the FMLN, have been insisting on passing another state of exception, but these efforts were soon translated into the Draconian quarantine regulations that were signed into law on May 5..

With regard to the coercive dimension of the government’s public health policy, Bachelet added that, “even in a state of emergency, some fundamental rights cannot be restricted or suspended, including the right not to suffer mistreatment and the fundamental guarantee against arbitrary detention.” The UN official also demanded that all alleged human rights violations within the context of the health crisis be investigated. [20]

Although the human rights violations by the Bukele administration during the pandemic have taken various forms and been amply documented, it is important to notice references to freedom of expression and access to information. Dozens such complaints have been filed with the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman. For example, the public has been denied access to reports on complaints by those held in the quarantine centers, which reveal that many detainees have not been informed of the results of their Coronavirus tests.

Impact of the photos of inmates crowded together

A third media incident and perhaps the most controversial one came with the photos of prisoners packed body-to-body in jails, some of them wearing masks. But the most concerning thing was the authorization of the use of force in the streets.

The Bukele administration is not the only one that has taken advantage of the pandemic to violate human rights and further harass political dissidents. Jeanine Añez of Bolivia is a great example of that as she not only pursues those who disagree with her during the pandemic,[21] but also continues to perpetuate the consequences of the coup d’etat against Evo Morales by forcing former members of his government to remain in the Mexican Embassy in La Paz because she will not authorize safe conduct passes.[22] But unlike Bolivia, the situation in El Salvador has become a topic of international debate. As for the treatment of prisoners, El Salvador has bucked the trend set in countries such as Nicaragua (where it was announced that prisoners would be sent to home detention), and Mexico. In the latter country an Amnesty Law was enacted to release women convicted of interrupting a pregnancy. This law also benefits the doctors, surgeons, and midwives who helped them. Amnesty was also extended to those accused of possession and transport of narcotics if they were in a situation of vulnerability, as well as indigenous people who were convicted without due process guarantees.

To understand the magnitude of the concern about what is happening in El Salvador’s jails (called “ticking time bombs”[23]), it should be noted that the country has the world’s second highest per capita incarceration rate in the world, after only the United States. This adds to the fact that the country’s detention centers have a capacity of approximately 18,000 inmates but currently house more than 38,000. The presence of COVID-19 in these facilities could give rise to a large-scale crisis.

Implementing a policy to relieve overcrowding in Salvadoran jails poses a big challenge. The population certainly supports measures that keep gang criminals behind bars. But a selective policy that could, for example, place people convicted of non-violent civil crimes under house address could be a temporary solution to reduce overpopulation in corrections facilities.

Bukele’s use of lethal force on the streets

Amidst the pandemic there has been an outbreak of violence in the Central American country. Bukele has used this to intensify his “zero tolerance policy” against the gangs by not only “mixing” members of different gangs in the same cells, but also authorizing the use of lethal force by the police and the army in the streets.[24] The order for the use of lethal force clearly reveals Bukele’s authoritarianism as he has carried out these policies in defiance of the express statements by national and international human rights organizations, who have issued alerts regarding the seriousness of the government’s actions.

In what has become routine behavior, instead of acceding to the cries and recommendations of human rights agencies, Bukele defiantly does the opposite, such as sealing the cells of inmates. “Now they can’t look out the cell door. This will prevent them from using signs to communicate with people passing in the hall. They are locked in the darkness with their friends from rival gangs,”[25] he tweeted.

But there is another little noticed variable. While Bukele’s tweets and decisions may recall episodes in which authoritarianism led to dictatorships in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s, or more recent suspensions of individual freedoms to contain popular unrest (such as by Sebastián Piñera in Chile, Lenín Moreno in Ecuador, and Iván Duque in Colombia), Bukele enjoys around 90% approval ratings in his country. [26] But no matter how high his current popularity, Bukele does not have the right to violate the human rights of the population or carry out actions that violate the law, the Constitution of El Salvador, and international law. Bukele seems to think that support in the polls gives him legal impunity to impose arbitrary and anti-democratic policies.

Despite the violations of human rights, the Salvadoran population seems to believe that an iron fist approach to the gang problem[27] is a successful way to stop violence. But that is nothing more than the success of the neoliberal and punitive narrative of fighting violence with repression, incarceration, punishment, and lethal force. This dehumanizing narrative is purported to be more successful than a policy of redistributing wealth and eliminating the inequality gap by increasing social spending on education, health, and housing. These kinds of progressive policies would give the marginalized sectors of the population an alternative other than gang affiliation.

The interview made it clear: Bukele is profoundly conservative

The fourth Nayib Bukele episode I wish to highlight was a social media interview with rapper René, also known as Residente, former vocalist with the group Calle 13.[28] Behind the facade of “Mr. Cool” and “everything’s under control,” Bukele revealed in this interview watched by young people from several Latin American countries that he holds views of which many outside El Salvador were unaware. For example, he is openly against a woman’s right to control her own body, specifically the right to terminate a pregnancy, and the President showed evidence of homophobia and transphobia.[29] During the interview in which Bukele said that “marriage is between a man and a woman,” he also said, “I do not favor abortion. I think that in the end, in the future, some day we will realize that we are committing genocide with abortions.” This statement did not sit well with the interviewer who said, “I do not agree with you.”

His personal views against marriage equality spurred a series of threats on social media against the LGBTI community in El Salvador.[30] Consequently, multiple organizations in the Salvadoran LGBTI Federation demanded that the Ministry of Justice and Security and the Attorney General’s Office investigate and “stop any public figures from making statements regarding LGBTI issues based on their personal and religious beliefs.”[31]

An organization that advocates for the rights of trans people, Comunicando y Capacitando Trans (COMCAVIS TRANS) says that between 2018 and September of 2019, 151 cases of forced displacement of LGBTI people in El Salvador has occurred. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has asked the Bukele administration to conduct investigations to ensure that hate crimes against this segment of the population do not enjoy impunity.[32]

Conclusions

There is mounting evidence that Nayib Bukele has not hesitated to violate the human rights of the population, openly practice authoritarianism, and illegally deploythe armed forces in an effort to increase and consolidate his personal power. To this end he uses and abuses El Salvador’s fragile democratic institutions. Proof of this is how he has used the COVID-19 pandemic to continue expanding authoritarian and illegal policies in violation of the population’s civil rights.

Furthermore, his policy of continuously incurring debt under the pretext of national security policy shows his ignorance of Latin American history. There is clear historical evidence that external debt and loans from international organizations (such as those Bukele is seeking), further entrenches the structural dependence of nations in the region.

Far from generating success through economic Independence, such international debt creates the exact opposite: austerity measures that condemn people to live in poverty. If such actions are not taken out of ignorance, then Bukele bears even more blame because he is acting as an agent to benefit the international financial institutions.

In addition, he operates as an ally of the United States by not hesitating to follow White House imperialist policies against progressive governments, such as support for the illegal occupation of Palestinian territory.

Given the now tarnished image of Bukele, at least on the international stage, the media is debating whether the Bukele administration is a success or failure. While Bukele commits systematic violations of human rights, outlets such as the Washington Post use an openly colonialist attitude when arguing that the United States should fix this, saying that, “The United States invested many years and billions of dollars in fostering democracy in El Salvador during and after its bloody civil war. It would be a tragedy if Mr. Trump allowed Mr. Bukele to undo that achievement on the pretext of fighting gangs and the pandemic.”[33] Although such narratives criticize Bukele, they grant the U.S. President the authority to decide on the internal affairs of other countries. Such discourse must be challenged to thwart the neo-colonization of El Salvador.

It must be said time and time again: Bukele not only poses a danger to the Salvadoran people, he also endangers the ability of progressive forces to construct a new world order in which human rights are protected, in which violence is addressed as a consequence of the structural inequality created by capitalism. This can only happen, however, when there is mutual respect among and solidarity among nations.

Alina Duarte is a COHA Senior Research Fellow.

Translated from the original Spanish by Jill Clark-Gollub.