Female federal prisoners are escorted through the Val Verde Correctional Facility in Del Rio, Texas. (Photo by Tom Pennington/Fort Worth Star-Telegram/MCT via Getty Images)

Obama is freeing more prisoners, but it’s still way fewer than previous presidents

Throughout his tenure, President Obama’s hesitation to use his executive pardon power has left critics scratching their heads. He granted zero clemencies during the first two years of his first term — except for Thanksgiving turkeys, of course — and the numbers have been in the low double digits every year since.

But recently Obama picked up the pace, commuting the sentences of 214 federal inmates. All of them were non-violent drug offenders, sending a clear message to the legislative branch.

“As successful as we’ve been in reducing crime in this country,” he said in a press conference, “the extraordinary rate of incarceration of nonviolent offenders has created its own set of problems that are devastating. Kids are now growing up without parents. It perpetuates a cycle of poverty and disorder in their lives. It is disproportionately young men of color that are being arrested at higher rates, charged and convicted at higher rates, and imprisoned for longer sentences. Ultimately, the fix on this is criminal justice reform.”

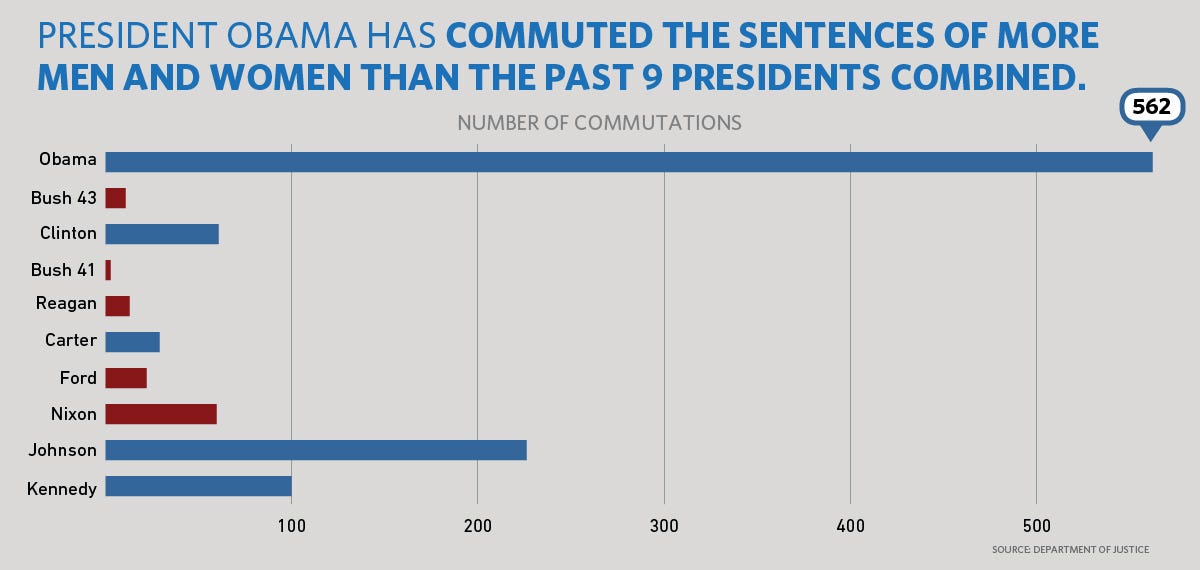

The recent action puts Obama well ahead of the last nine presidents in terms of commuting sentences — a fact that the White House emphasizes on its website with this triumphant graph:

The graph’s not wrong, of course, but it leaves out some crucial information. First, commuting sentences — or reducing an inmate’s time in prison — is only one of the ways to grant clemency, and it’s not even the most popular one. The full pardon, which consists of expunging an inmate’s record and restoring full rights, has historically been favored by presidents. There are also two other kinds of clemency grants, each much rarer: the respite, which is a temporary release often used to address medical circumstances, and the remission, which is the lowering or eliminating of fines.

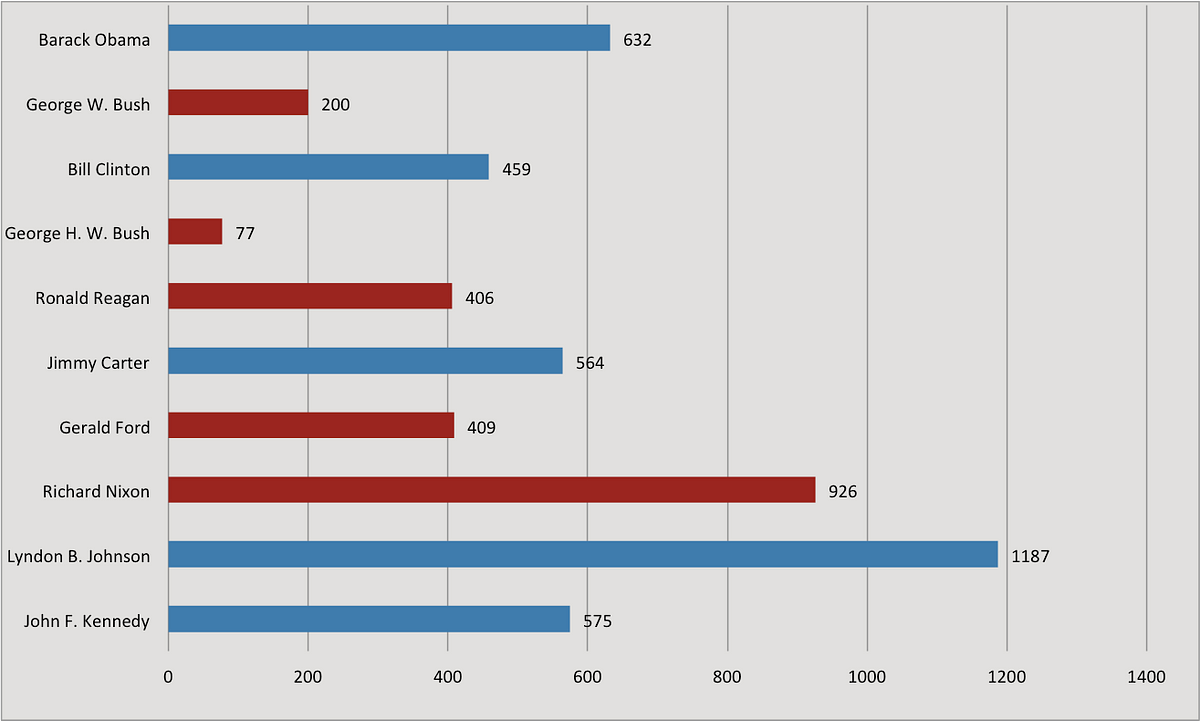

So here’s the same graph of the past nine presidents, but with full pardons, respites and remissions added into the mix, alongside commutations:

In terms of total recent clemencies, then, Obama’s in the middle of that pack at best.

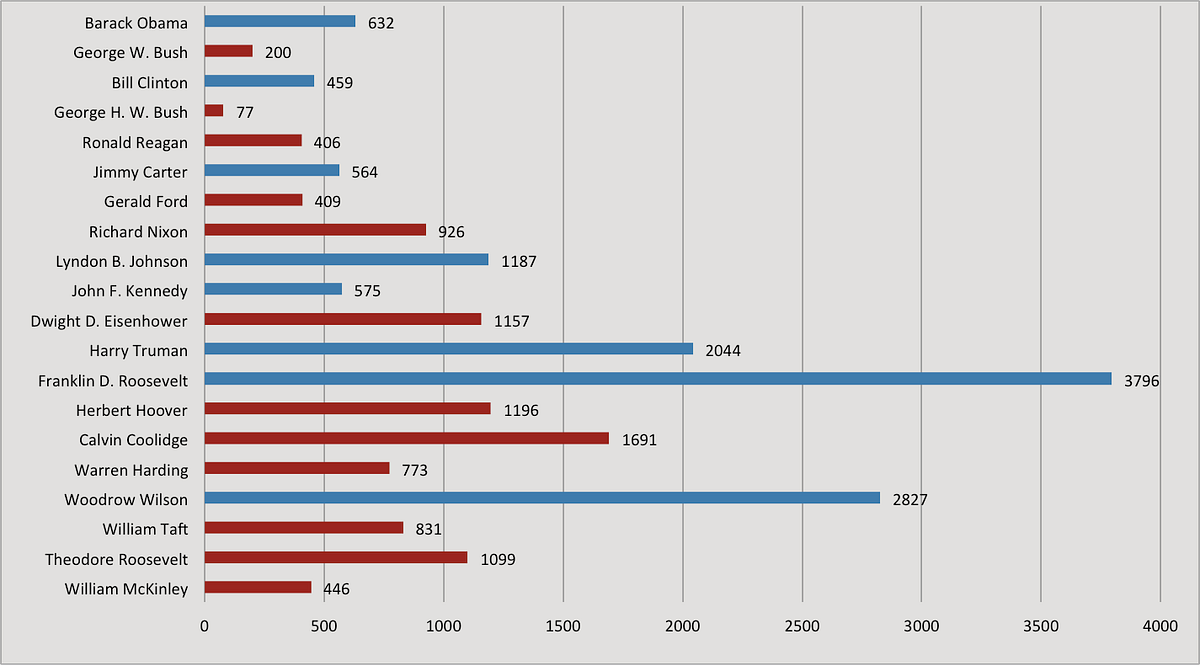

Then there’s the fact that the White House’s graph conveniently stops in the mid-20th century, around the time that executive clemencies started to drop off. “What was once a steady stream of presidential clemency grants has dwindled to a token few,” writes Margaret Colgate Love in the Journal of Law and Criminology, explaining that the numbers really took a nosedive during the Reagan years, when the War on Drugs was ramped up and tough-on-crime became the go-to political stance.

Look what happens to the same graph when we include presidents dating back to William McKinley, the earliest president for whom the Justice Department has stats:

Clemencies just aren’t what they used to be. In his final year, Obama has started swimming against the tide — but even if he swims fast, there’s no way he’ll come close to rivaling early 20th century American presidents. If he’s lucky, he might edge out Nixon.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, writes Love, “Pardons were granted frequently and generously at regular intervals over the course of each president’s term.” They weren’t concentrated at term’s end like they are now — instead, they were a regular part of presidential duties. In fact, between 1902 and 1933, there was only one month without a single pardon.

The reasons for granting clemency were all over the map, from “dying confession of the real murderer” to “enabling farmer prisoner to save his crops.” Parole didn’t make an appearance in the criminal justice system until 1910, so clemency was often the only way to cut an inmate some slack. Clemency also frequently functioned as political critique. Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft both felt that the death penalty should not apply to unpremeditated murder, and granted commutations accordingly. Woodrow Wilson, no fan of Prohibition, gave clemency to many liquor law violators in order to signal his desire for legal reform — a parallel to Obama’s 2016 strategy.

As the parole system took shape, the clemency system changed, too. In the mid-20th century, the two developed separate roles: parole emerged as a rehabilitation tactic, while clemency became more of a gesture of mercy. In the 1940s and ’50s the clemency application and approval process became more formal and more complex, and the increased paperwork led to a downturn in grants. But still, it was a pretty routine part of presidential life. Just check out Lyndon B. Johnson’s numbers.

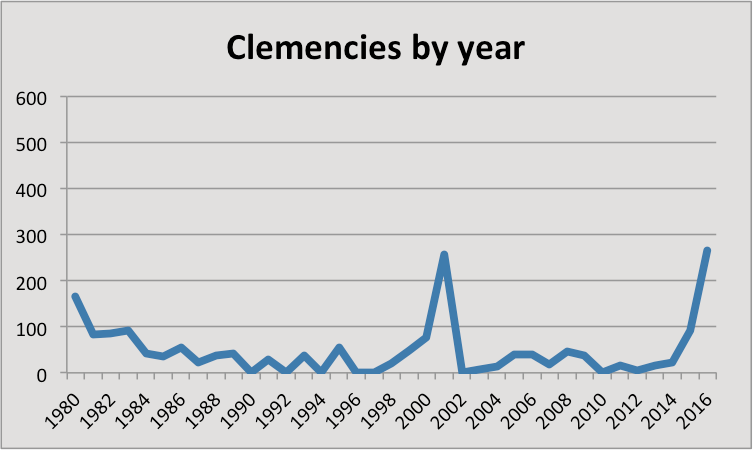

It all changed with Reagan. Love attributes the steep late-20th century drop-off to “the ascendency of retributivism in punishment theory” — that is, the rise in zero-tolerance and tough-on-crime attitudes toward criminals. “It became conventional wisdom that appearing ‘soft on crime’ could only get an elected official into trouble,” Love writes. In the 1980s and ’90s, presidents became fearful of granting clemency, as sympathy for law-breakers was no longer a desired character trait in politicians.

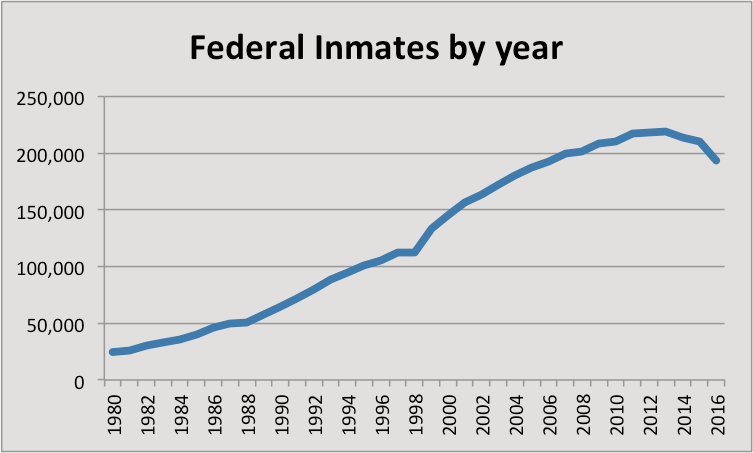

Mandatory minimums, the gutting of the parole system and the decline of executive clemency all resulted in more pathways into prison and fewer pathways out. As a result of these and other incarceration-oriented policies, the prison population ballooned. Look at the number of presidential clemencies next to the number of federal inmates over time:

The federal prison population has dipped a bit lately, but it’s still enormous. Even if Obama grants a slew of commutations here at the end of his presidency, it will hardly make a dent in the number of inmates that have been stuffed into federal prison since the beginning of the tough-on-crime era.

Still, Obama said he “thought it was important for us to send a clear message that we believe in the principles behind criminal justice reform, even if ultimately we need legislation.”

Meagan Day is a staff writer for Timeline. Features editor for Full Stop.