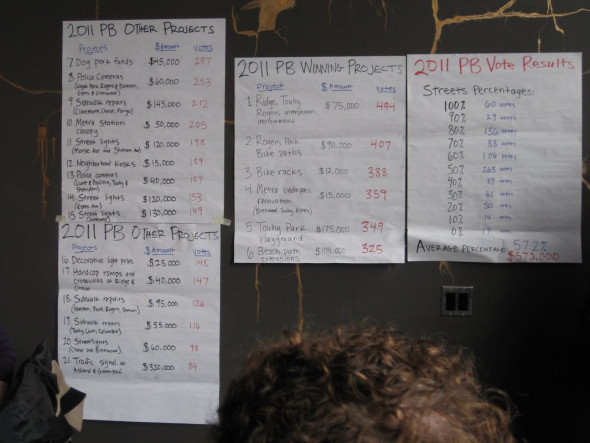

Above Photo: Courtesy of the Participatory Budgeting Project

Google is blocking our site. Please use the social media sharing buttons (upper left) to share this on your social media and help us break through.

This blog is part of the civic engagement blog series released in tandem with the “Building Civic Capacity in a Time of Democratic Crisis” white paper. To read the rest of the series, click here.

In 2007, I thought the City of Chicago and I had a pretty good relationship.

In 2007, I thought the City of Chicago and I had a pretty good relationship.

In 2008, I woke up from the little bit of the “American Dream” I thought I could achieve. As a black, queer woman growing up in low income family, it was less of a dream and more of a daydream, to be certain, but still a version of the middle class life promised to all “hard-working” Americans. But in the fall of 2007, I met my goal and purchased my first home. At the time it not only seemed to be a good idea because I wanted a place to settle down for a bit (rents were high and I had finally achieved some financial stability), but it was also, according to the dream, the thing I was supposed to do.

Then the housing market crashed. Our developer fled the country, leaving all the residents in our 39 unit building to fend for ourselves. We had no one but each other to rely on for advice, support, and to take care of housing needs. So I began to organize in my community, starting with my neighbors. I learned the procedures and processes needed to keep our building afloat, and despite unfinished units, a leaking roof and an unpaid pile of bills, we made it work.

By 2009, I was fully conscious that the relationship the City of Chicago had with me was purely transactional, and that as a resident, I was largely on my own and virtually powerless as an individual. But I learned that as a community of individuals, we have power to make real, lasting change. Together we faced what we couldn’t alone. It was during this time that I was introduced to participatory budgeting.

Participatory budgeting (PB) is a process where communities are given direct decision-making power over the budgets that impact them.

First developed by progressive activists and the labor party in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre in 1989, PB is a practice of democratic values. To date, there have been more than 3,000 PB processes around the world, and at its best, it provides a space for accountability and transparency between people and their governments.

The first PB process in the U.S. started in my neighborhood of Rogers Park – more specifically, in Chicago’s 49th ward. Alderman Joe Moore had learned about the process and decided it was something that might be good for our community. He was right.

When PB began in the 49th ward, I was working full time, in grad school part time, and serving as our condo board president representing us in housing court, working with banks and lawyers, and managing building issues. But when I saw a flyer from the Alderman’s office inviting community to come decide how we would spend $1 million to improve our ward, I made time to attend – and I brought a couple neighbors along.

In the neighborhood assembly I attended, I learned a lot. I learned what PB is and its potential impacts. I learned about the budget that the Alderman had to work with, how it had been spent previously, and how I could be involved in making decisions through our new PB process.

Two thoughts came to me that I’ll never forget:

- This just feels like democracy; and

- Why don’t we do this for more things?

As one of the many people who had their lives turned upside down in the housing crisis, I knew what could happen because of bad decision-making by a relatively small group of people. People who weren’t accountable to me or my community. It’s part of why PB was so immediately appealing. I was hooked.

Why PB? Why Now?

Participatory budgeting is a process that not only lets people exercise real democratic decision-making to control public budgets; it also lets them design their own democracy. Here’s how it works:

Planning: Communities and government officials work to identify goals for their process and the right portion of the budget to use for the PB process.

Design: Working together through an inclusive and participatory design process, communities and government write the rules for how PB will work for them.

The Process:

Idea Collection events kick-off the actual PB process with assemblies, pop-up events, and online platforms informing people about the budget, the process and how they can get involved while also collecting ideas for how to use the money and recruiting volunteers to help work on proposals.

Proposal Development: Volunteers, called Budget Delegates, spend the bulk of the process cycle working with government officials, their neighbors, and community institutions to research and create proposals that they believe will address community needs, benefit their neighbors, and that are feasible within the rules of the budget.

Community Vote: Final proposals are placed on a ballot and in assemblies, pop-up events and even online, the community at large votes on which projects they think should be implemented. In most places, voting is open to any resident that lives in the community. Suffrage is usually granted despite documentation status or whether residents are registered/eligible voters in traditional elections. Communities around the United States have also decided that PB is a great way to involve and educate youth; the average voting age is set at 14!

Implementation: Finally, the vote isn’t the end of the PB process. Winning projects are implemented by the usual government agencies and Budget Delegates often continue to meet to check on project status and give input when further decision-making is needed.

Now more than ever we need to lift up processes like PB that allow us to envision what our democracy can be. That let us create new spaces for local engagement, and establish relationships between people and governments built on trust.

When the people most impacted by a decision are brought into the decision-making process and given control we see better decisions, stronger relationships within communities, and higher levels of engagement as a result.

We see the reasons why democratic decision making is necessary pasted on the front pages of our newspapers and marching in our streets. PB is democracy at its core. Every person, regardless of citizenship status, gets to have their voice heard and their vote count in their community. We need to make our democracy reflect the people it serves and we must start in those places we know best: in our neighborhoods and in our cities.

PB is what the future of democracy looks like.