Above Photo: Palestinian farmer Elayan Shami, 62, stands near his field in the West Bank village of Battir. Sebastian Scheiner / AP.

The “Seam Zone.”

Israel Claims That Security Is The Only Reason It Denies Palestinians Access To The Seam Zone, But Data Obtained By MintPress Shows That Fewer Than 1% Of Permits Were Denied On Security Grounds.

Occupied West Bank — Taysir Amarneh, a farmer whose land is located west of Israel’s notorious apartheid wall, has been waiting 30 minutes for Israeli soldiers to open Gate 408 so he can enter his fields. The military is supposed to open the checkpoint at 11:15 a.m. but they’re often late, Amarneh explained. The army finally arrives a little after noon so that Amarneh can prune his olive trees.

A Wall Separating People From Their Land

In response to the outbreak of the Second Intifada (the Palestinian uprising against Israeli occupation), Israel decided to erect a wall separating the Occupied West Bank from the rest of Palestine in 2002.

The government justified the move as a way to block so-called terrorists from crossing the Green Line (1949 armistice line serving as the de facto border between the state of Israel and its occupied territories). However, most of the apartheid wall wasn’t constructed along the Green Line, instead, it was built inside the West Bank — essentially fragmenting the region. The space between the wall and the Green Line is known as the Seam Zone and makes up 9.4% of the West Bank. Israel designated the Seam Zone as a closed military area, meaning Palestinians need special permission to access their land there. This is where Amarneh’s farmland is situated.

Amarneh, council head of Akkaba Village where he lives, said that 80% of the village’s residents own land inside the Seam Zone while “very few people — 20% — have land inside the Palestinian Territory, which they can enter at any time.” This means the majority of Akkaba residents have to go through the bureaucratic maze of acquiring permits and waiting for the army in order to cultivate their land.

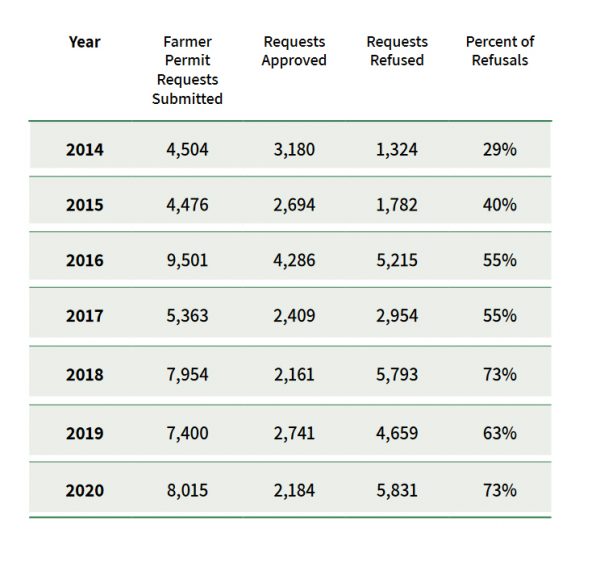

According to a new report from Israeli human rights organization HaMoked, the Israeli military is increasingly restricting Palestinian farmers’ access to the Seam Zone. HaMoked’s Freedom of Information request filed to the Jerusalem District Court found only 27% of farmers’ permit requests to enter the area were approved by the military in 2020, while 73% were denied — leaving tens of thousands of Palestinians unable to reach their land.

Israel has previously stated that security is the only reason to deny Palestinians access to the Seam Zone, but the data shows fewer than 1% of permits were denied on security grounds. Instead, most requests are rejected due to an inability to meet the military’s criteria for a permit.

“A person has a right to go to their land for any reason they chose,” Jessica Montell, HaMoked’s executive director, said in a statement, which continued:

These farmers are not asking to enter Israel, and in most cases there are no security concerns — and still they must prove they ‘need’ to reach their land, weather a bureaucratic nightmare to obtain the necessary permit. It is long overdue for Israel to dismantle those portions of the Barrier [apartheid wall] inside the West Bank and cancel the Seam Zone permit regime.”

Farmers Forced To Prove An ‘Agricultural Need’

Permit rejections have been steadily rising in recent years. According to HaMoked’s findings, in 2014, Israel denied 29% of permit requests. This number jumped to 55% in 2016 and 2017, and to 73% in 2018 before dipping slightly to 63% in 2019 and rising back to 73% in 2020.

The Israeli military is increasingly tightening its criteria on whom it lets into the Seam Zone. In 2009 — when the permit regulations were first released — applicants had to prove a connection to the land. In 2014, Israel updated the regulations to only allow landowners into the Seam Zone, thereby barring family members of landowners from the area. In 2017, Israel updated the regulations again. Now, farmers must prove an “agricultural need” to access their land.

“[A]s a rule, there will be no sustainable agriculture need when the size of the plot for which a permit is requested is tiny, not more than 330 square meters [about 3,550 square feet],” the military said in their new order.

HaMoked petitioned the Israeli High Court against this tiny-plot rule in 2018. In 2020, the court issued an order nisi (a court order that will come into force at a future date unless a particular condition is met) on the petition and held a hearing on Oct. 28. HaMoked expects a court ruling in the next few months.

As a result of these rejections, fewer Palestinians are attempting to apply for a permit, Montell noted.

“What is happening on the ground is fewer and fewer Palestinians are even trying to enter those areas and, of those who try, fewer are succeeding,” Montell told MintPress News. “Some of the Seam Zone is just Palestinian agriculture, but a lot of the Seam Zone is settlement areas. So, settlements are expanding while Palestinians are being dispossessed from those areas.”

Amal Zeid, a farmer who owns 67 acres in the Seam Zone, explained in the report how her family has lost hope over the restrictive measures. “Every time I want a permit, like most people I know, it’s a battle. My sisters haven’t gotten a permit for years. They’ve given up. But we have to maintain our connection to the land,” Zeid said.

In 2020, on behalf of seven Palestinian farmers, HaMoked petitioned Israel’s Supreme Court to raze the Qaffin Village segment of the apartheid wall, writing:

[I]t has been proven beyond doubt that the existence of the Barrier leads to the erasure of Palestinian life in the Seam Zone created by the segment and the severance of connection between the lands and their owners.”

Amarneh, one of the petitioners, told the court:

Today many farmers have abandoned their lands west of the Barrier. Most of the residents of Akkaba now work inside Israel, or they rent land to the east of the Barrier. I myself inherited from my father 260 dunams [64 acres] of land that are in the Seam Zone; of them, 60 dunams [15 acres] were seized to build the Barrier itself. I have another 74 dunams [18 acres] east of the Barrier. Today I mostly grow olives on the land in the Seam Zone. I don’t grow seasonal vegetables anymore.”

Gate 408, where he waits to enter his land, is along the Qaffin segment.

Losing Their Livelihoods And Heritage

Israel’s ever-expanding restrictions on permits have deteriorated Palestinian life. Farmers whose land is in the Seam Zone have seen their income plummet and their lands turn barren.

“I calculated that as a result of the fence, I lose about 25,000 shekels ($7,500) in income every year,” Jihad Haresha, a farmer from Qaffin, said in a HaMoked press release. “Before the fence, I would tend the land together with my nieces and nephews. Other relatives would also come and help harvest. Now no one gets permits. My wife and I have to do it alone.”

Ahmad Abadi, a farmer who owns 10 acres in the village of Barta’a in the Seam Zone, was granted a two-year permit in 2019. Yet his permit is limited to 40 entries per year on the grounds that he owns a tiny plot of land. Abadi joined HaMoked’s petition against the tiny-plots policy after the court rejected his appeal of the permit.

“My connection to the land cannot be quantified into a number of entries,” Abadi said during a hearing before the Appeal Committee. He continued:

I have a deep emotional connection to my land. The memories of my childhood are linked to it. Every time I enter my land, I remember my father and my mother. I remember the rock on which my father used to boil coffee and tea. I continue this tradition – I use that same rock to boil coffee and tea. This maintains my connection to my past and to my family. Reducing my connection to my land to a calculation of the crops grown there is offensive. It in no way captures my connection to my land.”

Last year, Abadi invested 7,000 shekels ($2,250) into growing tobacco but lost it all once his 40th entry was made and he could not return.

“I asked someone else to go and take the tobacco for yourself before the pigs destroy it all,” Abadi said. Without regular access, Abadi watched his land become overrun with pests.

Abadi, who now works as a construction worker in 1948-occupied Palestine (modern-day Israel), grows olives on his land in addition to tobacco but mentioned that with the restrictions he doesn’t rely on his crops anymore. Instead of taking olives from his field, he’ll just go and buy a bottle of olive oil from a local store.

Amarneh’s village of Akkaba has seen its agricultural economy collapse. Amarneh explained the village residents have stopped selling fruit. Shepherds have reduced the number of goats and sheep they graze. “Someone who had 100 goats, now has only 30 or 12, because they can’t enter the land behind the wall,” Amarneh said. He, himself, once had 400 sheep but now has only 100.

Farmers in the Seam Zone have mostly switched from cultivating high-yield vegetables to mainly producing fruit trees like olives. This change has depleted their earnings and left them to abandon farming altogether. According to a 2003 report from humanitarian aid donors to Palestine, switching from vegetables to olives reduces a farmer’s income by 95%.

Yet even olive cultivation has suffered due to the restrictions. Amarneh owns land on both sides of the apartheid wall and said the differences in production are stark.

“The land in the Palestinian territory, where I can enter any time I want, for each dunam (quarter acre), I’ll average between 70-90% of [my potentional olive harvest],” Amarneh said. “But whatever is behind the wall, will give me 30%.”

As the Palestinian olive harvest season comes to a close in the next few weeks, farmers in the Seam Zone reflect on how this draconian permit system has soured a once joyous time. Zeid said:

I remember myself as a child. I would spend so much time on the land. The olive harvest was like a big festival. All of our relatives would meet and spend hours and days together, adults and children alike. I remember we would sometimes sleep out on the land. We can’t do that anymore. You have to file documents. You need a permit. There’s a checkpoint.”

Amid Israel’s labyrinthine permit procedures, Palestinians are losing a part of their heritage.