Above Photo: Members of the RCMP look on as supporters of the Wet’suwet’en Nation block a road outside of RCMP headquarters in Surrey, B.C., on Jan. 16, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward

In a pre-dawn raid on Feb. 6, the RCMP arrested six land defenders of the Gidimt’en clan of the Wet’suwet’en nation at a blockade protesting the Coastal GasLink pipeline project. They were released later the same day but protestors at the Gidimt’en checkpoint await another raid by RCMP. Enforcing an injunction, the RCMP have said that they will use “the least amount of force necessary.” But protesters and observers believe any action will result in police violence.

The RCMP has been called “an occupying foreign army” by Indigenous blogger M. Gouldhawke, who does so based on the fact that the RCMP still maintain their own camp in Wet’suwet’en territory and “continue to harass people at the long-running Unis’tot’en anti-pipeline camp.”

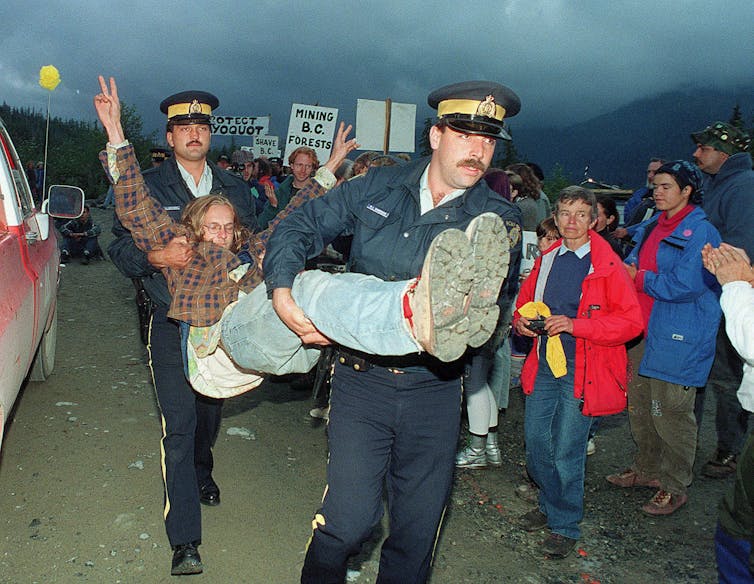

As a young woman, 27 years ago, I stood on the line in Clayoquot Sound with land protectors trying to block logging trucks from taking down an old-growth forest. I witnessed the process of intimidation and systematic arrests by police. However, most of the people on the line were Euro-Canadian, middle class or relatively privileged folks in fleece and wool.

They were not hit with billy clubs, or called derogatory names, such as “squaw” or “chug.” To the state, Indigenous protesters represent a much greater threat than environmentalists demanding a park.

Britain’s illegal rule

Canada’s unlawful domination over Indigenous Peoples was articulated from the moment of the country’s inception.

Prior, imperial rule was enacted through imperial policies from Great Britain, such as the Gradual Civilization Act, the pre-cursor to the invasive and controlling Indian Act.

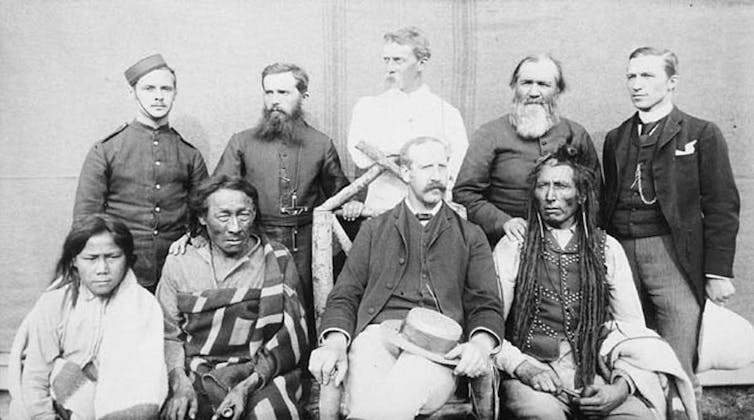

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police were established in 1873 as the North-West Mounted Police. They were the enforcers of the recently formed Anglo-settler state’s policies and to ensure that the Métis, Cree and Saulteaux did not take control in the northwest.

The Hudson’s Bay Company had recently closed shop and left behind a “European void” in the former Rupert’s Land, an area soon reclaimed by the Métis. Louis Riel was summoned to lead the Métis in their struggle to protect their community. He would later be hanged as a political prisoner, but he was not Canada’s first Indigenous political execution.

On Nov. 27, 1885, eight Indigenous men were also hanged by the state for their role in the Northwest Rebellion, also known as the North-West Resistance, as written about in William Cameron’s 1926 book Blood Red the Sun.

Imperial domination can be seen as a matter of class, gender and “race” with white ruling-class supremacy. Prompted by upper-class advisers such as Donald Smith (a.k.a. Lord Strathcona), John Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, sent an army west to kill the Métis and take their lands, making way for the national railway project.

With the assistance of police, the state decimated the Métis at Red River in 1870, again in 1885 and then subsequently flooded the area with Anglo, Protestant, anti-French and anti-Native settlers. In 1961, the RCMP reprinted a Prince Albert Daily Heraldarticle in their magazine, Quarterly, which claimed that Louis Riel was “mainly responsible for the unsettled conditions which led to the founding of the Force….”

According to a 2012 Globe and Mail article, strands of the rope used to hang Riel for treason were given to former Manitoba premier Duff Roblin as well as to the RCMP who guarded Riel in his cell.

Respecting sovereign Indigenous nations

Many Indigenous Peoples seek the earlier nation-to-nation relationships spelled out in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the British North America Act of 1867. And some Indigenous activists look forward to restoring sovereign and self-governing lands in a way prior to the imposition of empire in Turtle Island, imagining how this could look today.

Today, Indigenous people own less than one per cent of all lands in Canada. This process has clearly been both unlawful and unethical.

Later in life, when I worked in the Yukon co-facilitating a racism-reduction project, “Together for Justice,” I came to understand a few things about the RCMP. I learned that some individual RCMP members wanted to be seen as kind human beings, which is challenging given that they work for a gun-carrying, para-military force with a history of violence against Indigenous Peoples. At that point, the organization was contending with its role in a number of Indigenous prison deaths, including that of Raymond Silverfox, who perished in his cell from pneumonia at the age of 43.

The RCMP see themselves as having two roles: one of law enforcement and the other of community policing. It is through the second of these roles where their opportunity to be most helpful or humanitarian resides. If police were successful at addressing and stopping violence against women and keeping women and children safe, we would see a different kind of society.

The RCMP have long had the disdainful role of enforcing the Indian Act, restricting the movement of on-reserve status Indians, arresting Indigenous people for using ceremony, and for the kidnapping of Indigenous children from their families to the internment camps known as “residential schools.”

Here in Tiohtià: ke/Montreal, on the territory of the Kanien’kehá: ka, police are remembered for their role in the Oka Crisis/Mohawk resistance.

Last month, Indigenous young people occupied the B.C. Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum office in Victoria in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who have opposed the Coastal GasLink pipeline in northern B.C. The occupation ended with arrests by Victoria police.

While we know that prejudice may be rooted in social attitudes, and can be transformed, those who work for the RCMP are required to perform social violence, maintain the status quo and do what folk-singer Billy Bragg identified as “defend wealth.”