Above Photo: Members of Reclaim the Block in Minneapolis, Minnesota protesting Mayor Frey’s press conference about the 2020 budget. PHOTO BY NANCY MUSINGUZI

Reclaim the Block, a coalition of local organizations, looks to a future where Minneapolis divests from the police department and invests in community-based solutions and safety.

In dramatic effect, a Minneapolis resident dumps a bag of money onto a podium during public comments at the final City Council meeting on the 2020 budget last month. The person with them, who identified himself as David, is addressing the council members.

“This is $193.40,” David says, then begins to explain that the money represents the $193 million budget Mayor Jacob Frey proposed to give the Minneapolis Police Department in 2020, more than one-third of the city’s general fund. The budget sparked protest from a number of Minneapolis residents and activists—many who attended the meeting to voice their opposition, including members of Reclaim the Block, a coalition of Minneapolis organizers and community members who advocate for divesting from police and into community-based solutions.

After the group’s protest of the 2020 police budget at three public meetings in the final months of 2019, the City Council voted to move $242,000 from the police budget and into the Office of Violence Prevention, a broad-reaching office that has the agency to fund community services in the name of violence prevention.

The budget shift was small compared to some of the other successes residents and local organizers have had over the past year and a half while advocating for the city to divest from the Minneapolis Police Department and into violence prevention. The group argues that large issues facing the city such as homelessness, opioid addiction, and mental health crises are not only not solved by the policing, but exacerbated by them. To get at the root causes of these problems, Reclaim the Block says, the city needs to invest in community-based solutions and services that are tailored to each issue.

While the coalition seeks to educate people year-round about community-based solutions, some of the group’s most visible work is at public government meetings where people like David advocate for a future with decentralized public services.

Sliding a coin from the pile of money, David announces, “That’s like taking a little bit less than this quarter out of this pile of money.” He pauses to draw attention to how the pile of bills dwarfs the single coin, then continues, “This quarter actually really matters because the folks at the Office of Violence Prevention can make this money do a lot of work in our communities,” David says. “We all know the folks who somehow manage to feed a room full of people on a shoestring budget like this, but just because we can stretch a dollar doesn’t mean we have to keep doing it, especially when our city has more than enough money to address the [city’s] issue[s].”

David and his companion’s display is effective and echoes the sentiment of the dozens of residents who addressed the council that evening: Fund communities, not cops.

A call for a new approach

In recent history, Minneapolis activists and organizers have made headlines calling on the city’s political leadership to defund police departments and put that money into community organizations that are making strides in violence prevention.

Reclaim the Block, which David is a part of, was created as a movement in 2018 specifically to address the 2019 budget—last year they inspired the City Council to not only create the Office of Violence Prevention, but move $1.1 million out of the Minneapolis Police Department’s budget and into the fund. That was the first time the city had showed real interest in investigating public safety options other than traditional policing.

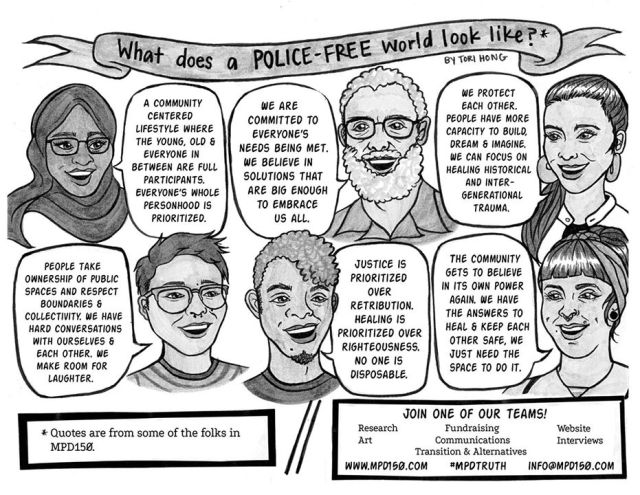

In 2016, a coalition of organizations—similar to those in Reclaim the Block—created a report detailing the Minneapolis Police Department’s 150 years serving the community to show that policing is not the answer to community violence and its related issues, such as homelessness, mental illness, drug and alcohol abuse, but in fact can worsen and contribute to it.

A key finding of the report is that there are “viable existing alternatives for policing in every area in which police engage.”

The report, called MPD150, traced the history of the Minneapolis Police Department, from the period of slave patrols—groups tasked with preventing slave riots and capturing enslaved Africans who ran away—to modern-day U.S. police departments, and failed attempts to reform the department’s lack of “real accountability.”

To invest in those viable alternatives, the community needs the support of the mayor or City Council to adjust the city budget says Oluchi Omeoga, a core team member of Black Visions Collective, which was one of the organizations involved in MPD150.

A key finding of the report is that there are “viable existing alternatives for policing in every area in which police engage.”

“But, to shift our community to be less dependent on the police department,” Omeoga says, “we need the people in the community to actually have discussions around why do we call the police, what do the police actually do, and what are the alternatives that we need in order to keep our communities actually safe.”

Members of Black Visions Collective and other organizers lead those community conversations and help to educate their communities about police alternatives. The alternatives range from services to call—instead of calling the 9-1-1—for people in mental health crisis, to organizations that assist people experiencing homelessness or drug addiction.

Decentralizing who to call

For mental health crises, Hennepin County’s Community Outreach for Psychiatric Emergencies is a hotline and mobile team of mental health professionals who can be dispatched in the county.

Kay Pitkin, the manager of COPE, says the crisis line is not a replacement for emergency responders—it can take 30 minutes to an hour for a mobile team to reach a patient, and they only operate during the week—but can provide more in-depth, comprehensive care and deescalate situations before they turn into public safety issues.

“Really what a person in a mental health crisis needs is mental health care,” Pitkin says.

Operating for more than a decade, COPE has a $4 return on investment, meaning that for every dollar invested into the program, it returns $4 of benefit to the community through costs avoided and other societal benefits.

COPE also partners with the Minneapolis Police Department and has crisis responders embedded in five precincts who respond to mental health-related 9-1-1 calls. According to Pitkin, even though the police show some resistance to working with mental health responders, the improvement in the mental health calls proves the co-responding program works. The earmarked $300,000 in the 2020 budget for the co-responders program allots enough funding to continue those embedded positions.

Decriminalizing Drug Abuse and Mental Health Illness

The most common criminal charge for people incarcerated in Minnesota is drug-related. Instead of criminalizing drug users suffering from the opioid epidemic, organizers of Reclaim the Block and MPD150 advocate for the decriminalization of drugs and harm reduction services that provide health care and supplies to active drug users.

One such place is Southside Harm Reduction Services, a volunteer-led program providing clean syringes to intravenous drug users and advocating for drug policing reform.

Jack Martin, Southside’s executive director, says that the police are enforcing drug war policies that are harmful to drug users while harm reduction services meet users where they are. Providing people with the tools to avoid disease allows them to stay alive and connect with other resources if they so choose, according to Martin.

“That’s what keeps people safe,” he says.

Leaders in these services like Pitkin and Martin stress the importance of being in network with other services and knowing what solutions are available for the population they are serving.

“We have relationships with just about everybody,” Pitkin says. Helping someone through a mental health crisis can involve coordinating medication, finding stable housing, and connecting them with legal services—all of which could require a different service.

Funding

The restrictions on services such as COPE and Southside Harm Reduction circle back to funding. Both services are able to partially fund with grants, and Southside takes individual donations, but COPE’s budget is affected by local government.

Grace Berke, the community coordinator for Powderhorn Park Neighborhood Association, argues that a lack of transparency in the way government officials talk about funding contributes to the minimal input into violence prevention services.

Berke says that when officials don’t research or include how much money it costs to fully fund a solution, they have no context for the significance of the proposed funding.

For example, the $242,000 being moved into the violence prevention fund.

“We are investing too much money in incarceration-based policing and not enough money in community-based safety.”

“People tend to compare those dollar amounts to their own income,” Berke explains, but in terms of funding an effective community program “it may be two full-time employees and part of an operations budget.”

Just stating that the government is putting $242,000 toward a problem is “different than saying ‘We’re putting $242,000 toward this problem and the need is $60 million,’” she says.

Even though the 2020 budget passed the City Council with a unanimous vote, several council members expressed their dissatisfaction with the amount of money going toward violence prevention.

During the final vote, one council member described the moment as “a tipping point.”

“I even hear from police, we can’t arrest ourselves out of this,” council member Cameron Gordon said.

Police department spokesperson John Elder wouldn’t comment on the mayor’s budget, but in response to the creation of Reclaim the Block and the community’s requests of divesting from the police, Elder says that it is “certainly people’s right to do as they wish, it’s not ours to second guess.”

Neither Mayor Frey nor City Council President Lisa Bender could be reached for comment, but Bender stated in the final budget meeting that she thinks the “police department needs a complete overhaul of its budget.”

“We are investing too much money in incarceration-based policing and not enough money in community-based safety,” Bender said before voting to approve the budget.

Transitions Take Time

To organizers like Omeoga of Black Visions Collective, the council member’s statements are baseless and in direct opposition to their statements.

Oemoga described the council as “playing a very safe game, as far as what waves they want to make and where they want to push.”

Even if local government supported divesting from the police rapidly, the transition is unprecedented and the organizers don’t pretend that they have all of the answers moving forward.

“It’s all about practice,” says Sophia Benrud, a core team and staff member of Black Visions Collective. “As we transition into something and out of something else, you’re always going to find gaps, and I think that you have to be emergent with that. Communities that have been systemically disenfranchised throughout history have always come up and filled the gaps in the ways they need to because that’s how we survive.”

Benrud urges people—including her City Council members—to understand that the transition takes time.

“Why would you think the transition is going to happen in a year?” Benrud asks. “We gave [policing] time, and it’s still proving to not actually do anything, so why not allow something else to transform and shift and change and grow with the same commitment that’s [been given] to the police department?”