Above photo: From Dreamstime.com

Google is blocking our site. Please use the social media sharing buttons (upper left) to share this on your social media and help us break through.

Note: This article was originally published on Nov. 8, 2017. It argues that the rising debt in retail will cause more stores to close, a decline in jobs and a hit to the economy. This is another sign that we need to push for a Guaranteed Basic Income and more locally-owned businesses, especially worker-owned cooperatives.

The so-called retail apocalypse has become so ingrained in the U.S. that it now has the distinction of its own Wikipedia entry.

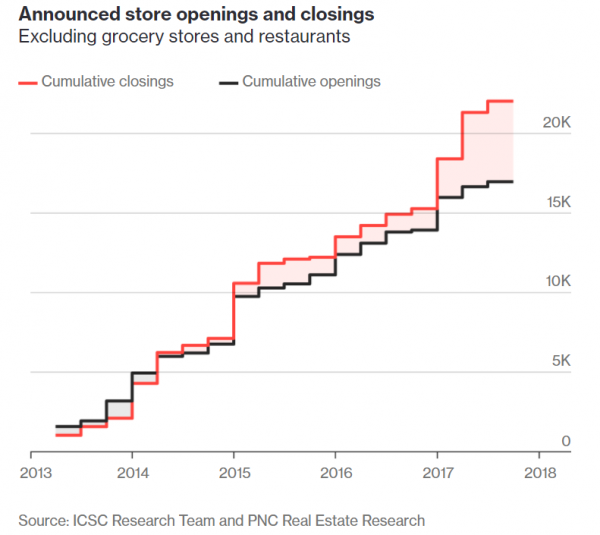

The industry’s response to that kind of doomsday description has included blaming the media for hyping the troubles of a few well-known chains as proof of a systemic meltdown. There is some truth to that. In the U.S., retailers announced more than 3,000 store openings in the first three quarters of this year.

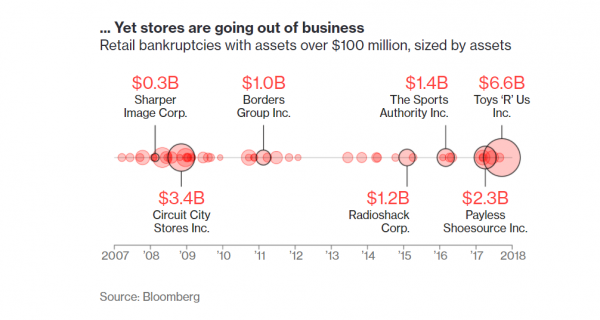

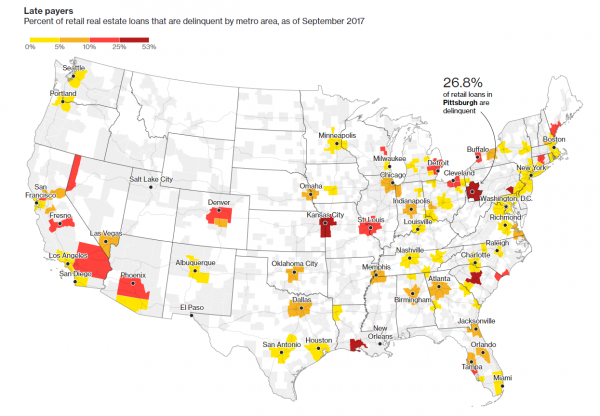

But chains also said 6,800 would close. And this comes when there’s sky-high consumer confidence, unemployment is historically low and the U.S. economy keeps growing. Those are normally all ingredients for a retail boom, yet more chains are filing for bankruptcy and rated distressed than during the financial crisis. That’s caused an increase in the number of delinquent loan payments by malls and shopping centers.

Late payers

The reason isn’t as simple as Amazon.com Inc. taking market share or twenty-somethings spending more on experiences than things. The root cause is that many of these long-standing chains are overloaded with debt—often from leveraged buyouts led by private equity firms. There are billions in borrowings on the balance sheets of troubled retailers, and sustaining that load is only going to become harder—even for healthy chains.

The debt coming due, along with America’s over-stored suburbs and the continued gains of online shopping, has all the makings of a disaster. The spillover will likely flow far and wide across the U.S. economy. There will be displaced low-income workers, shrinking local tax bases and investor losses on stocks, bonds and real estate. If today is considered a retail apocalypse, then what’s coming next could truly be scary.

Until this year, struggling retailers have largely been able to avoid bankruptcy by refinancing to buy more time. But the market has shifted, with the negative view on retail pushing investors to reconsider lending to them. Toys “R” Us Inc. served as an early sign of what might lie ahead. It surprised investors in September by filing for bankruptcy—the third-largest retail bankruptcy in U.S. history—after struggling to refinance just $400 million of its $5 billion in debt. And its results were mostly stable, with profitability increasing amid a small drop in sales.

Making matters more difficult is the explosive amount of risky debt owed by retail coming due over the next five years. Several companies are like teen-jewelry chain Claire’s Stores Inc., a 2007 leveraged buyout owned by private-equity firm Apollo Global Management LLC, which has $2 billion in borrowings starting to mature in 2019 and still has 1,600 stores in North America.

Just $100 million of high-yield retail borrowings were set to mature this year, but that will increase to $1.9 billion in 2018, according to Fitch Ratings Inc. And from 2019 to 2025, it will balloon to an annual average of almost $5 billion. The amount of retail debt considered risky is also rising. Over the past year, high-yield bonds outstanding gained 20 percent, to $35 billion, and the industry’s leveraged loans are up 15 percent, to $152 billion, according to Bloomberg data.

Even worse, this will hit as a record $1 trillion in high-yield debt for all industries comes due over the next five years, according to Moody’s. The surge in demand for refinancing is also likely to come just as credit markets tighten and become much less accommodating to distressed borrowers.

Retailers have pushed off a reckoning because interest rates have been historically low from all the money the Federal Reserve has pumped into the economy since the financial crisis. That’s made investing in riskier debt—and the higher return it brings—more attractive. But with the Fed now raising rates, that demand will soften. That may leave many chains struggling to refinance, especially with the bearishness on retail only increasing.

One testament to that negativity on retail came earlier this year, when Nordstrom Inc.’s founding family tried to take the department-store chain private. They eventually gave up because lenders were asking for 13 percent interest, about twice the typical rate for retailers.

Store credit cards pose additional worries. Synchrony Financial, the largest private-label card issuer, has already had to increase reserves to help cover loan losses this year. And Citigroup Inc., the world’s largest card issuer, said collection rates on its retail portfolio are declining. One reason that’s been cited is that shoppers are more willing to stop paying back a card from a chain if the store they went to has closed.

The ripple effect could also be a direct hit to the industry that is the largest employer of Americans at the low end of the income scale. The most recent government statistics show that salespeople and cashiers in the industry total 8 million.

During the height of the financial crisis, store workers felt the brunt of the pain when 1.2 million jobs disappeared, or one in seven of all the positions lost from 2008 to 2009, according to the Department of Labor. Since the crisis, employment has been increasing, including in the retail industry, but that correlation ended as jobs at stores sank by 101,000 this year.

Retail jobs lag

Compared to all private jobs, positions at physical stores have grown less over the last 10 years, both in numbers and wages.

The drop coincides with a rapid acceleration in store closings as bankruptcies surge and many of the nation’s largest retailers, including Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Target Corp., have decided that they have too much space. Even before the e-commerce boom, the U.S. was considered over-stored—the result of investors pouring money into commercial real estate decades earlier as the suburbs boomed. All those buildings needed to be filled with stores, and that demand got the attention of venture capital. The result was the birth of the big-box era of massive stores in nearly every category—from office suppliers like Staples Inc. to pet retailers such as PetSmart Inc. and Petco Animal Supplies, Inc.

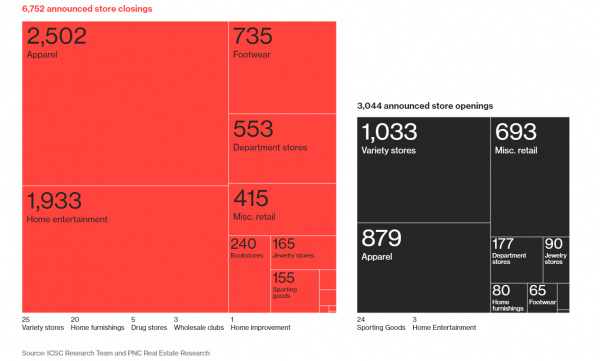

Now that boom is finally going bust. Through the third quarter of this year, 6,752 locations were scheduled to shutter in the U.S., excluding grocery stores and restaurants, according to the International Council of Shopping Centers. That’s more than double the 2016 total and is close to surpassing the all-time high of 6,900 in 2008, during the depths of the financial crisis. Apparel chains have by far taken the biggest hit, with 2,500 locations closing. Department stores were hammered, too, with Macy’s Inc., Sears Holdings Corp. and J.C. Penney Co. downsizing. In all, about 550 department stores closed, equating to 43 million square feet, or about half the total.

Clothing stores and entertainment chains lead store closing surge

Q1–Q3 2017 data

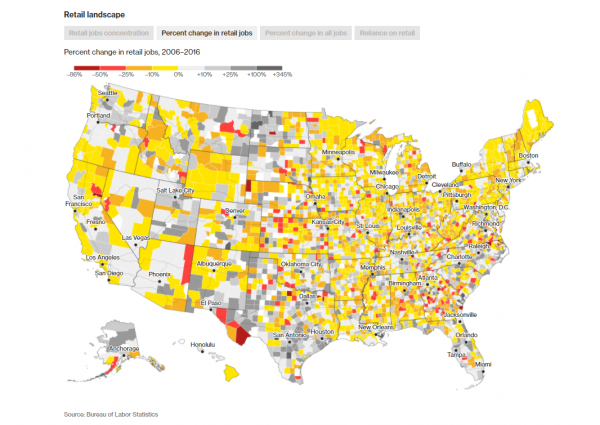

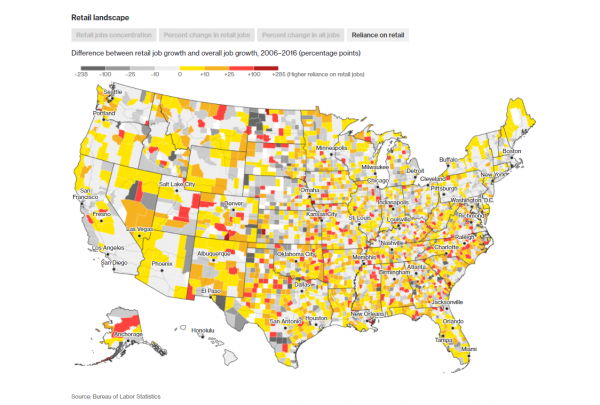

States like Ohio, West Virginia, Michigan and Illinois have been among the hardest hit, with retail employment declining over the past decade, and now those woes are likely to spread. Many states, such as Nevada, Florida and Arkansas, have overly relied on retail for job growth, so they could feel more pain as the fallout deepens. In Washington since 2007, retail jobs have grown 3 percentage points faster than overall job growth.

Retail jobs growth by state

New England and rust-belt states in particular have struggled, January 2007 to September 2017

Exposure to low-end retail jobs varies by state. Alabama, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Mississippi and South Carolina have the highest concentration of cashiers, who have an average wage of $21,500 a year. And on a regional basis, Washington Parish north of New Orleans has a higher percentage than anywhere in the country, at twice the national average. Florida relies on retail salespeople more than any other state. In Sumter County, west of Orlando, retail jobs nearly doubled over the past decade.

Retail landscape

The path to the middle class in retail is often to become a supervisor. There are 1.2 million of them, and their average annual salary is more than twice that of a cashier at $44,000. In that category, many of the same states have the most on the line, with Alabama, West Virginia, South Carolina and Montana containing the highest ratio of these workers.

One response to the loss of store-based retail jobs is to note that the industry is adding positions at distribution centers to bolster its online operations. While that is true, many displaced retail workers don’t live near a shipping facility. The hiring also skews more toward men, as they make up two-thirds of the workforce, and retail store employees are 60 percent women.

The coming wave of risky retail debt maturities doesn’t take into account that companies currently considered stable by ratings agencies also have loads of borrowings. Just among the eight publicly-traded department stores, there is about $24 billion in debt, and only two of those—Sears Holdings Corp. and Bon-Ton Stores Inc.—are rated distressed by Moody’s.

Even the stable department stores are billions in debt

Most recent long-term debt-to-total assets ratio

“A pall has been cast on retail,” said Charlie O’Shea, a retail analyst for Moody’s. “A day of reckoning is coming.”