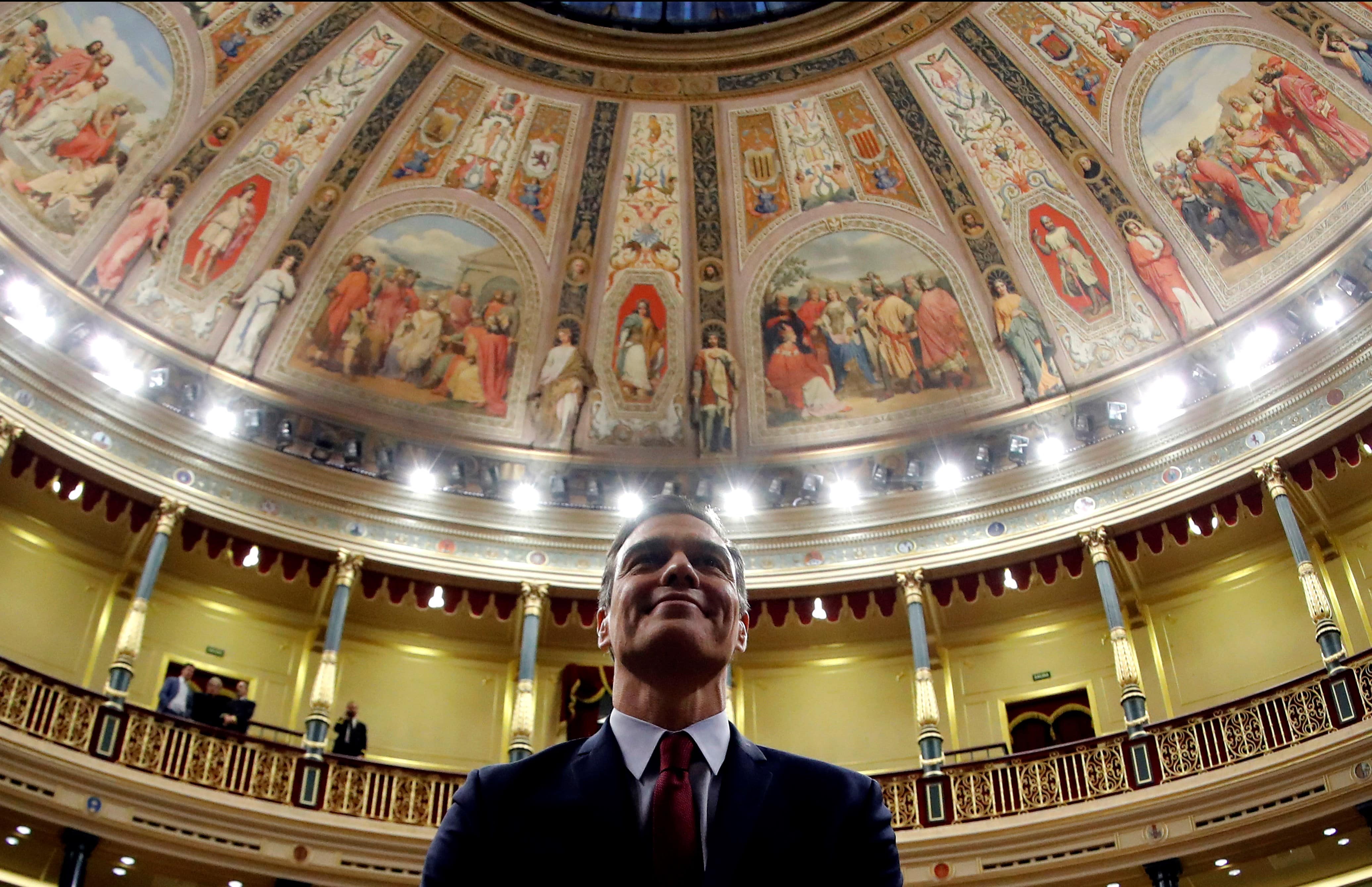

Above Photo: From Occupy.com

“Corbynism has come to Spain” leaving business leaders “trembling,” wrote the Telegraph last week in response to news that the Mediterranean country had elected its first truly left-wing government in decades.

Following months of political deadlock, nearly a year without a government and four general elections in as many years, January 7, 2020, saw Spanish Parliament swear a Socialist Party (PSOE) and Unidas Podemos (UP) coalition into power.

The vote narrowly allowed the PSOE, Spain’s traditional left-wing party, to form a government with the far-left party, UP, which was born out of the Indignados and 15M, an anti-austerity movement that seized national support starting between 2011 2015.

UP’s leader, Pablo Iglesias, will now serve as deputy prime minister and will have responsibility over several key roles, including labour minister and equality minister. The coalition will be the first genuinely socialist government in Spain since the 1930s. It will also be the country’s first coalition government since the restoration of democracy in 1978.

The Socialists’ narrow victory limited the gain of the far-right party, Vox, which in opposing feminism, immigration and LGBT rights echoed sentiments spawned during General Francisco Franco’s 36-year-long dictatorship.

In electing a socialist coalition, Spain is countering the politics of nationalism and populism that has been rising across Europe. The change in fortune of the Spanish Socialists is giving hope to many, during dark political times on the continent, that Spain could lead a socialist democrat revival in Europe.

Hailed by its architects as the “most progressive government since Spain’s Second Republic” of 1931 to 1939, the country’s new government is being supported by Catalan and Basque regionalists. Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, the leader of the PSOE, said he will reopen dialogue about the long-standing Catalan separatist conflict, which remains one of Spain’s most pressing political issues.

RAISING TAXES AND WORKERS’ RIGHTS

Podemos’ leader, Pablo Iglesias, spoke recently about how the real “betrayal” of the Spanish nation had consisted of “attacking workers’ rights, selling off public housing to vulture funds, and privatising the welfare state and public services.”

Working in coalition with the austerity-opposing Iglesias to create greater social justice and improve workers’ rights are top priorities for Sanchez. The prime minister plans to raise income taxes on those earning more than €130,000 a year. The income tax for higher earners will increase by 2 percent, and 4 percent for those earning over €300,000.

The government also plans to reverse some of the labour market reforms introduced by the previous conservative government, including legislation that made it easier and less expensive to fire employees.

Other measures agreed upon by the new coalition including the regulation of housing rental prices, which would put Spain in line with similar legislation introduced in Belgium and Germany.

For people on the right, and its supportive media ecosystem, the Sanchez-led coalition represents a “radical” government made up of an explosive combination that support the “Catalan coup” and “Basque terrorists.”

However, as the Washington Post notes, such “left radicalism” is nowhere to be seen. A far cry from what the right has labelled as a “fiscal attack on the middle-class,” the new coalition’s tax increase is relatively small, affecting only the richest 0.4 percent of taxpayers.

THE CRIPPLING EFFECTS OF AUSTERITY

In 2011, when the conservative Popular Party (PP) won a resounding victory in parliamentary elections, Spain’s government led by Mariano Rajoy announced a new round of austerity measures. The austerity reform was designed to slash public spending and halve the public deficit from around 8 percent of GDP in 2012. It was described as the “most austere budget of the post-Franco era,” equated to 27.3 billion euros in budget cuts and a freeze on public sector pay.

Two years later, in the first quarter of 2013, Spain’s unemployment rate had soared to a new record of 27.2 percent of the workforce. Statistics unveiled by the Spanish Statistical Office show that between 2009 and 2015, investment in the social protection of families had fallen by 11.5 billion euros.

According to Unicef, between 2008 and 2014, the proportion of children living below the poverty line in Spain increased by an average of 9 percent, reaching almost 40 percent. It could be argued that rising child poverty levels coupled with soaring unemployment is testament that austerity doesn’t pay.

Unidas Podemos arose as an anti-austerity party aimed at stamping out divisions. Since forming in 2014, Podemos (which means ‘We Can’) emerged as one of Europe’s most prominent parties, securing the support of millions of voters in the wake of Spain’s deep recession. In 2017, grassroots party supporters rallied behind the its far-left chief and re-elected Iglesias as leader.

In the wake of swearing in the new coalition last week, the Spanish government is now comprised of members of the anti-austerity Podemos, as Iglesias serves as deputy prime minister in charge of social rights and sustainable development while his wife, Irene Montero, is minister of equality.

With high-profile, left-wing, anti-austerity figures now in key government roles, Spain’s long years of austerity, and the crippling effects it has produced, could be numbered.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM PORTUGAL

Both PSOE and Podemos, as well as critics of the new coalition, can look to their neighbour Portugal as a model of a successful minority, left-wing government backed by the hard left. Since Socialist Party leader Antonio Costa formed a left-wing coalition government in Lisbon in November 2015, ousting the center-right coalition that had resolutely maintained years of fiscal austerity, Portugal’s economy has been steadily growing following a decade of stagnation.

Alongside a buoyant economy, a falling deficit and booming exports, Portugal is widely considered one of the best places in the world to live. Armed with a socialist government allied with a far-left anti-austerity coalition, Spain could now be on track to follow in the footsteps of its neighbours and stamp out its failed austerity regime.

However, not everyone in Spain is convinced that the new coalition can succeed. As Pedro Llorente, a postal worker in Andalusia, told Occupy.com, “This government will last until the budgets are presented, which will not be approved, and elections will be called again.”

Nonetheless, to many, the new socialist, left-wing government of Spain offers hope of progressive change during a time when right-wing populist movements cheered by right-wing media are on the rise across Europe.

As the Washington Post wrote: “If the coalition succeeds, it will be an example for Europe on how to stem the political rise of the dangerous xenophobic far-right.”