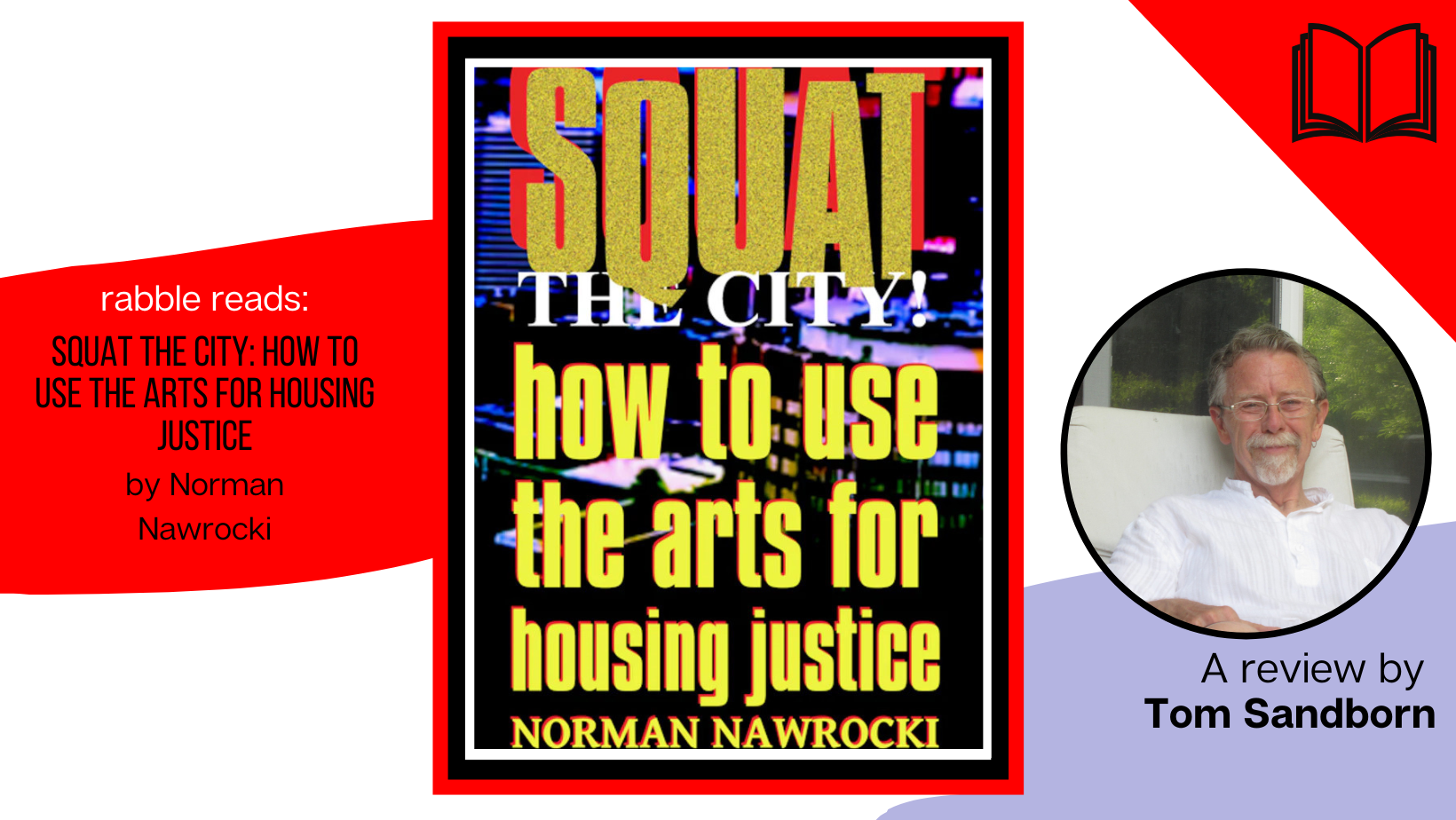

Norman Nawrocki’s new book explores the creation of an activist network in Quebec that combined art and fighting for justice for the unhoused.

The great American organizer and songwriter Woody Guthrie, scrawled on his instrument the memorable phrase, “This machine kills fascists” during World War II. Norman Nawrocki, Vancouver born and Montreal based organizer, author, musician, dramatist and educator, would likely not make that grand or lethal a claim for his latest book, Squat the City: How To Use the Arts for Housing Justice.

But he does want the book to serve as a tool, a weapon and an inspiration for people around the world who are facing our own era’s capitalist authoritarians and their murderous lust for profits and power.

Nawrocki has spent most of his time as an organizer fighting for housing justice, and his book is a fond memoir of some of the many artistic projects he has co-created with precariously housed and unhoused people struggling against evictions and homelessness. It illustrates the argument that creative arts can be an important way for people at the bottom of the social ladder to link with each other, tell their truth and mobilize against the powerful forces of repression and exploitation that structure and oppress their lives. The book is good humoured and modest, but fierce. Nawrocki’s last book, 2024’s wonderful novel Vancouvered Out, had its protagonist returning to his former west coast home to discover it much changed for the worse by developers and real estate speculators. It is a grim text, but in the end a hopeful one, and this year’s book is a guide to the possibility of that hope. The main themes of that guidebook are respectful engagement with the homeless and precariously housed as full partners in creating art for social change, and the deep wells of joy and creative fun that people creating art together can generate.

The book opens with paired appeals to artists and activists, appeals that are also challenges and invitations to figures on both sides of the arts/activism dynamic. They are invited to find each other locally and let their disparate strengths and resources act as insurrectionary force multipliers. He knows this is possible because he has been doing it all his adult life, and he is eager to share both the inspiration and the challenge with his readers.

One of the projects that the author lovingly details in this lively politico/artistic memoir is Un Logement pour une chanson (A Home for a Song), “housing rights cabaret” that toured 16 of Quebec’s poorest neighborhoods in the early 1990s. This was a joint project involving the author and his performance partner Sylvain Coté, who constituted the “rebel news orchestra /cabaret rock and roll band” Rhythm Activism and local volunteers and advocates associated with a network of housing activist groups in the province, Le Front d’action Populaire en reamenagement urbain (FRAPRU).

In each neighborhood, over a creative period of months, the two members of Rhythm Activism met with local activists and crafted a version of the cabaret specific to the neighborhood. Repeating characters in each neighborhood version included villainous “condo vampires” out to drain the life out of the neighborhood and hated political figures like Quebec premier Robert Bourassa and Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. To these figures Nawrocki, Coté and local activists added locations and personalities from the neighborhood, plus a lot of good-natured clowning and singing, plus engaging comedy sketches on the topic of housing rights and wrongs, featuring a game show that glorifies the attacks of developers on vital neighborhoods as progress.

The cabarets were staged in community centres, bingo halls, soup kitchens and church basements. They reached thousands of Quebecois and generated lots of positive media for FRAPRU and its campaigns.

The photos and fliers from this campaign enliven the book and give a wonderful sense of the intricate blend of grass roots radicalism with high concept performance and European cabaret styles that Rhythm Activism generated together with their community collaborators. Lots of Canadians in my baby boomer cohort dabbled in activist art practice, particularly in earlier eras when our political and class masters were willing to throw small packets of money at artists through Local Initiative and Opportunities for Youth funding or the Canada Council for the Arts.

But Nawrocki has never quit mining the rich veins of inspiration he found in his early projects, and his impressive bibliography attests to decades of hard work. But always hard work that is energized by laughter and joy. I suspect he would echo that great anarchist figure Emma Goldman, who insisted “If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution.”

Buy this book and share it with your accomplices and collaborators, whether you are an artist, a musician, an activist or just someone looking for secure , affordable housing. It is full of wisdom, jokes and inspiration for us all.