Above Photo: All together now: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night…” Danny Moloshok/Invision/AP

While USPS workers deliver Christmas gifts, Mark Dimondstein, president of the American Postal Workers’ Union, is busy fending off demands to privatize the mail.

President Richard Nixon created this vast mail-managing entity in 1970 by turning its old Cabinet-level predecessor, the U.S. Post Office Department, into a government-owned corporation, caving to union demands after hundreds of thousands of postal workers went on strike for better wages and collective bargaining rights. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan tried to change the USPS’s public status and sell it off for cash. He failed, but in 2006, Congress passed the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act, which mandated that Postal Service retirement health care* be pre-funded, and arguably contributed to a long-term financing crisis that continues today.

Meanwhile, the American relationship to the mail changed. The rise of the internet cut down on letter-sending, stamp-buying, and analog bill-paying; private shipping services like Fedex and UPS crowded the delivery market.

That hasn’t stopped postal privatization fears from re-emerging. President Donald Trump has frequently targeted the 242-year-old agency, citing inefficiency and criticizing its role as a government-run mail monopoly. This month, the U.S. Department of the Treasury released a Postal Task Force Report outlining a strategy for securing the U.S. Postal Service’s sustainable future. It recommended cutting wages for postal workers and eliminating collective bargaining, to cut down on service costs. It floated several new monetization models, including leasing out parts of post offices, and even selling third parties access to personal mailboxes. Perhaps most upsetting to postal fans, the report also considered reevaluating the terms of the office’s Universal Service Obligation (USO), which today ensures that every address, no matter how remote, is served.

Reading between the lines of the report, many postal workers and advocates looked at these recommendations and saw a renewed push for privatization. A White House-released government reform plan released this June put it more bluntly, recommending a sale or an initial public offering. But Mark Dimondstein, the president of the AFL-CIO-affiliated American Postal Worker’s Union (APWU), thinks he knows how to save it, without selling it.

CityLab recently sat down with Dimondstein in his downtown D.C. office to talk about how the post office is uniquely positioned to breach the urban-rural divide, how the USPS can cut its losses and even expand its offerings, and why old-fashioned snail mail might be the last truly private communication left. The conversation has been edited and condensed.

When you took office, you mentioned ushering in a new vision for the Postal Service’s future. What was that vision?

I believe that the Postal Service is a public national treasure that belongs to the people in the country, and that the union needs to be in alliance with the people of the country to make sure that they keep what’s theirs. Along with that, we’re certainly interested in good jobs—ones that pay family-sustaining wages, and community-building wages, and benefits and rights.

We knew that there were powerful forces that were in the process of challenging the future of the public institution—there are powerful forces that would like no public goods of any kind, and the post office is part of the public good. So we came in with a vision that the post office can have a great, vibrant and robust future and unite with the people of this country.

There’s a lot more the post office can do. It’s not something that is dying. It’s something that there are forces that would like to kill.

Who wants to kill it? And how?

I think the answer lies in the Office of Management Budget Report from June. If you go back to that report, it says that the White House is going to restructure the post office and that there’s an opportunity to privatize it, including an initial public offering.

If you want to lower wages you’ve got to take away collective bargaining, which of course gives workers a voice at work. And the main bastion uniting with the people of this country to save this public entity are the postal unions. So if you want to get the privatization going, you want to lower the wages and benefits to fatten it up and entice someone to buy it. And you need to get rid of the main political force that’s the obstacle to privatization.

What’s so bad about privatization?

The postal service now goes—by mandate and by obligation—to every single address, no matter who we are, where we live, what age, what gender, what nationality, what income group, or anything else. There’s no way anybody can do that if it’s a question of profit. It has to be set up as a public service.

The Task Force Report implied that the universal mandate could be maintained even under a privatized model, though they did acknowledge it would require “a policy determination of who should carry the USO burden, how to fund it, and who will pay for its cost.” It also highlighted examples of various stages of postal privatization working in other countries, like Germany and New Zealand. What, in your view, is fundamentally wrong with the idea that the U.S.’s universal mandate can survive under privatization?

It hurts the individual customer. It hurts businesses, particularly small business but even some of these larger businesses. If you go and ask Amazon and eBay, they’re not for postal privatization. They need that public Universal Service Obligation that goes everywhere. FedEx and UPS put a lot of their own packages into the postal mail service, because they can’t go down my sister’s dirt road in Vermont and make money. Or when they do, they have surcharges and extra costs attached to it, because of either distance or lack of population density. But the post office is there anyway.

The post office was set up with no tax dollars since 1970. It’s funded by the product and the services, and it serves everybody, and it’s working. There’s a lot of money in it, and those billions—probably about $70 billion a year that comes in postal fees and products—if someone can get a whole bunch of that themselves and make a profit, then that’s what they’re going to want to do.

But when you do that, wages go down—which hurts our community, hurts working people, hurts our economy, and hurts our country—and services and costs go up. There’s no way you can have universal service if you turn it over to a private company.

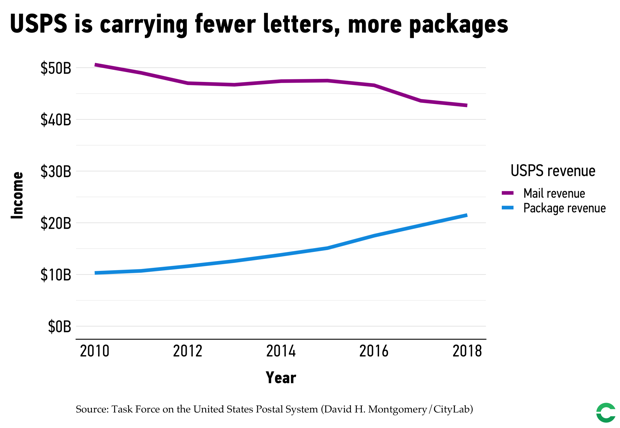

Our saying is that the internet taketh, and the internet giveth. There are more packages and fewer letters because of the internet. So while they’re taking some first-class mail, they’ve given a whole lot of e-commerce and packages.

We talk a lot about the “last mile.” Amazon will sort packages first, and drop them right to the letter carriers, who then handle that last mile to the customers’ house.

But 30 percent of e-commerce packages get returned. And once they get returned, postal workers handle the “first mile”—the trip back to the company. It’s the postal workers who have to sort it and get it to where it’s going. E-commerce has a back-and-forth process, if it’s going to work for the customers—and the post office, again, is the best set up for that, because they’re traveling to each mailbox and each address.

That seems to be a really valuable—and unique—feature of the Postal Service as it exists today: It’s reaching the rural areas that a lot of other services can’t, or just don’t.

A bipartisan bill proposed by Republican Congressman Jason Chaffetz, the Postal Service Reform Act of 2017, included a clause that would allow the post office to take over more functions of the state.

The Office of the Inspector General of the USPS did an interesting report last year talking about foot traffic. [Customers visited post offices around the country an estimated 2.7 billion times in 2016.] And once you get people in the door, you can provide a lot of services—in both rural and urban neighborhoods.

What could those expanded functions look like?

The most obvious one is expanded financial services. What that would be in reality is some basic financial services such as paycheck cashing and more remittances overseas. They could make a little money on it and they can make the post office that much more viable. Postal banking is creating an actual bank, which we’re for, but it would take legislative change. There’s a lot that the post office can be doing that doesn’t take any legislative changes.

Most of the post offices in the industrialized world and beyond have an array of financial services that are not pure banking. Even the U.S. allowed it from 1911 into the 1960s. But when you’re dealing with the Department of Treasury, you’re dealing with the banking industry. There are about 80 million people in this country who don’t have access to basic banking. And while the banking industry is fleeing our communities, they still don’t want a public option.

A lot of low-income hard-working people are paying 10 percent of their income for fees and services around the alternative financial industry—the legal loan shark industry. The people in this country are getting ripped off by the predatory payday lending and check-cashing industry. We could do it at the post office for a couple bucks and put it on a piece of plastic, where there are no fees.

The other thing we’re hot on is expanding vote by mail. It increases voter participation, it’s the most secure, and it provides a paper trail. It takes away a lot of what we would generally call voter suppression, such as voting on Tuesday—a workday, not a federal holiday. If it’s vote by mail, you can do it at your own pace, on your own time, and you could pay more attention to the issues.

The Task Force also suggested other ways to make the USPS profitable—by leasing out space within the physical post offices to other retailers, or by selling hunting licenses, or by “franchising the mailbox,” which would involve keeping the mailbox monopoly, but allowing regulated access to “certified companies,” for a fee. What do you think of those suggestions?

We’re fine selling hunting licenses—there’s all sorts of licensing we could do. But renting out our post offices is absurd. We should have postal services in there. We’re not interested in becoming private entities or stores.

And the idea of letting third parties have access to personal mailboxes completely destroys the privacy and sanctity of mail. That was always one of the great things about the post office: People use their mailboxes to send and receive things that are personal, and legal, and maybe financial. Nobody else can go into that mailbox. It’s the last bastion of private communication—emails are not, texting is not, cellphones are not. Look at how many absentee ballots are in the mail, for example. Your ballot’s coming to you, and it could be taken before you get it. Or you’re mailing it, and it could be taken if anybody’s going into your mailbox.

But the USPS does need to find more money somewhere. The Task Force recommends more closely aligning postal workers’ wages with those other federal workers, which you’ve already mentioned would be bad news for the employees you represent. What about their suggestion to reevaluate the retirement funding structure for postal workers?

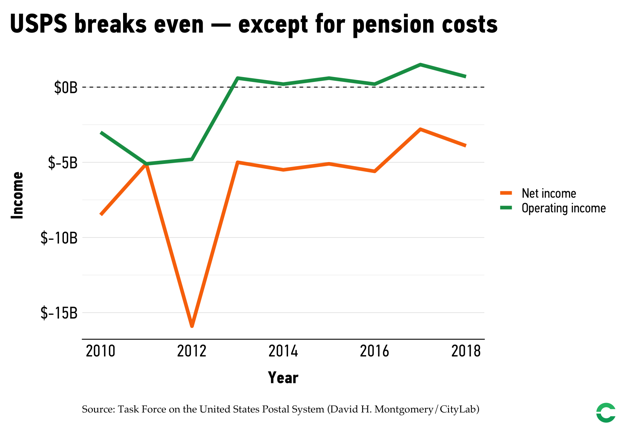

The post office’s financial problems, almost all of them, go back to this 2006 Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act, when the Postal Service was burdened with something no other company and no other federal agency is burdened with: pre-funding retiree health insurance at 100 percent, 75 years into the future.

Seventy-five years into the future in 2006 meant that not only was the post office paying for people that didn’t yet work for the post office, it was paying for people who weren’t even born. It took $5.5 billion a year from the Postal Service budget—which is not taxpayer money—into the federal treasury for something they were meeting their obligations on already. That was a “fix.” But it was also a manufactured financial crisis by Congress.

There was one point in the Task Force Report about changing the way in which the pre-funding is structured—restructuring the “unfunded actuarial liability for retiree health benefits” based on the population of employees at or near retirement age. That would be a fair way to restructure. But they don’t even need to do that! No company is 100 percent funded like that and it doesn’t need to be—you can pay as you go.

Are there also ways to increase revenue without turning to franchising, or leasing, or cutting wages? The Task Force recommends removing the cap on commercial mail pricing, for example.

We believe that there should not be a price cap on any of the mail. There wasn’t a price gap until 2006—another consequence of the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act—and all aspects of the mail in the post office were still the cheapest option in the industry. So it was already proven that without a price cap, the post office was not going to raise rates willy-nilly.

Finally, we talked a bit about how much the Postal Service is trusted and, indeed, loved by many in the U.S. Why do you think that is?

Think about the post office even in terms of bringing normalcy to communities; and safety to communities. After hurricanes, floods, and fires, the first thing that comes back is often postal service.

A lot of the letter carriers in particular, but also our window clerks, save people from scams. When they find mail piling up in a box for an elderly customer, they know something is wrong. They knock on the door. There are all sorts of stories where postal workers have found people in car accidents or house fires. They play these heroic roles, and then just go back to work.