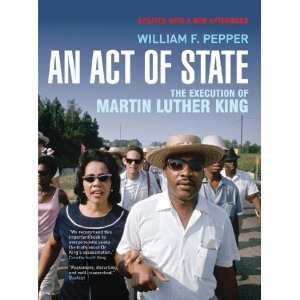

Above Photo: National Park Service/Flickr

On the anniversary of the death of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. we published the transcript of a speech given by the King family lawyer, William Pepper, which provided detailed evidence that shows James Earl Ray was a patsy set up to take the blame for a murder he did not commit. Pepper points to a conspiracy between the FBI and Memphis police as the source of the assassination with the fatal bullet being shot by a Memphis police officer. See Who Killed Martin Luther King, Jr, and Why?

The Washington Post broke with recent corporate media practice by daring to raise questions about who killed Martin Luther King Jr., as William F. Pepper and Andrew Kreig explain.

For the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder, The Washington Post last week overcame its tainted history of softball coverage and published a hard-hitting account quoting the King family’s disbelief in the guilt of convicted killer James Earl Ray.

The bold, top-of-the-front-page treatment on April 2 of reporter Tom Jackman’s in-depth piece—“The Past Rediscovered: Who killed Martin Luther King Jr.?” — represents a major turning point in the treatment of the case for the past five decades by mainstream media. Print, broadcast and all too many film makers and academics have consistently soft-pedaled ballistic, eye-witness and other evidence that undermines the official story of King’s death.

This time, the Post and Jackman, an experienced reporter, undertook bold but long overdue initiative. One can only hope that it leads to similar coverage — rigorous and fair — for other history-changing events, including current ones that are inherently secret.

The Post’s MLK Success Formula

Jackman’s method was relatively simple. Reporters use it routinely on other stories that are not so politically sensitive as King’s death. In this instance, the reporter quoted family members and other experts and provided balance with other perspectives.

Thus, Jackman wrote near the top of his long column:

“In the five decades since Martin Luther King Jr. was shot dead by an assassin at age 39, his children have worked tirelessly to preserve his legacy, sometimes with sharply different views on how best to do that. But they are unanimous on one key point: James Earl Ray did not kill Martin Luther King.

“For the King family and others in the civil rights movement, the FBI’s obsession with King in the years leading up to his slaying in Memphis on April 4, 1968 — pervasive surveillance, a malicious disinformation campaign and open denunciations by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover — laid the groundwork for their belief that he was the target of a plot.”

That wasn’t so hard, was it?

Memphis Commercial Appeal investigative reporter Marc Perrusquia appears to be a kindred spirit to Jackman. Based on extensive reporting for his newspaper, Perrusquia documented a new book released last month A Spy In Canaan: How the FBI Used A Famous Photographer To Infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement. This is the story of Ernest Withers, who took iconic photos of King and other civil rights leaders during the 1950s and 1960s. The implications are disturbing, given the smear campaign against King especially before his death.

Tone Deaf NPR Falls Flat

Sadly, straightforward reporting can be uncommon in these kinds of sensitive cases, particularly if a news outlet decides to prioritize its previous reporting, or the goodwill of its law enforcement sources.

Thus, typical of MLK death anniversary coverage was the April 3 report on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered show by NPR’s Justice Correspondent Carrie Johnson, previously a Washington Post reporter for a decade ending in 2010 covering justice issues. As part of a series “1968: How We Got Here,” her NPR segment’s title was “Conspiracy Theories About MLK’s Death Continue, But Investigators Say Case Is Closed.”

That title using “Conspiracy Theories” is a smear. It’s used by reporters and academics to discredit alternative researchers ever since the CIA secretly distributed to its operatives in April 1967 the now-declassified “CIA Dispatch 1035-960.” The 53-page CIA memo urged agency personnel to persuade their establishment contacts to use the term “conspiracy theorist” to undermine critics of the 1964 Warren Report on the JFK assassination, thereby helping to discredit New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s grand jury investigation of a fatal plot alleged to include CIA personnel scheming against the president.

Even without knowing that history, many career-minded reporters and their news managers these days instinctively use the term to demonstrate that they are team-players too sophisticated to be taken in by the alternative media.

In this instance, the NPR team on the show hosted by Mary Louise Kelly quoted one of this article’s co-authors, William Pepper, but in ways that implicitly discredit his views.

One way that the NPR approach trivialized Pepper’s experience was by focusing heavily on his involvement with a mock trial of the defendant Ray in 1993 and not five decades of relevant experience, especially his research findings in the late 1990s.

A more neutral and informative perspective for readers might have been to note that Pepper had worked in the 1960s with King in expanding the civil rights leaders’ reform agenda. Later, the King family asked Pepper to reinvestigate the murder. Pepper’s street reporting among witnesses and suspects in the Deep South led to evidence that won the King family a civil jury verdict in 1999 that discredited the official story, and then to three Pepper books about the evidence, most recently “The Plot To Kill King” published in 2016.

Instead, the NPR reporter and her team placed more credence, as evident by the biased headline for the segment, on former government investigators who had worked on the case years if not decades before the 1999 civil trial.

Instead, the NPR reporter and her team placed more credence, as evident by the biased headline for the segment, on former government investigators who had worked on the case years if not decades before the 1999 civil trial.

NPR’s unfamiliarity with the basic evidence was particularly obvious in its column about its radio report: NPR repeatedly misspelled the name of the lead defendant in the King Family’s civil suit. NPR kept naming him as “Lloyd Jowers” instead of as “Loyd.”

MLK as a ‘Black Life That Mattered’

Authorities have long pinned all blame for King’s murder on the ill-educated petty thief James Earl Ray, who was supposedly motivated by racism. The evidence Pepper uncovered shows that Ray’s movements were manipulated by a handler so that he would be at the scene when a professional team undertook the hit.

Not coincidentally, the misleading story about Ray carries a number of false historical implications.

For one, a theory of purely racially motivated killing unrealistically confines the murder and King’s focus to the Jim Crow-era of Deep South segregation and related civil rights abuse. That makes today’s younger audiences think of King and his message as largely out of date.

In fact, King’s legacy remains highly relevant to today. During the last years of his life, he focused on economic justice, anti-war activity and coalition building. By 1968, these goals were far more threatening to the power structure than civil rights.

Rather than repeat some of the many apt tributes to King’s legacy that honored his memory last week, let’s focus on a colossal irony:

King’s was a black life that truly “mattered.” And it mattered in significant part because the “Poor People’s Campaign” that he envisioned could unite whites and others in a mass movement far beyond the scope of the largely black-led civil rights marches in the Deep South that included some white supporters.

And yet many of those most focused currently on injustice issues have scant suspicion that the circumstances of the great prophet’s death, like that of the two Kennedys, are in dispute. But the facts are relatively knowable and understandable to those who disregard the “conspiracy” smear and dare to look at the scientific, witness and other evidence.

And yet many of those most focused currently on injustice issues have scant suspicion that the circumstances of the great prophet’s death, like that of the two Kennedys, are in dispute. But the facts are relatively knowable and understandable to those who disregard the “conspiracy” smear and dare to look at the scientific, witness and other evidence.

The pioneering scholar Peter Dale Scott developed, beginning in the 1970s, the alternative terms “Deep Politics” and “Deep State” to replace the biased smear term “conspiracy theory.” Scott popularized the term in a series of books that continue to the present.

No reasonable person would argue, of course, that every anti-government theory has merit. Good evidence exists. So does bad evidence, including misinformation, disinformation, and whacko nonsense that floats around partisan circles.

Democracy in Danger

King’s death provides lasting lessons for problems that we face now.

One difficulty is how to understand vital justice-related issue, many of which are inherently secret until final stages of the judicial process (and some of which remain secret even afterward).

That means we in the public must rely on institutions, dishonest, or otherwise flawed. But we can know from the study of historical materials whether these institutions are honestly addressing such momentous issues as the King murder. Those insights can provide a Rosetta Stone for current mysteries.

That’s why Tom Jackman’s treatment for the Post of the King case provides a basis for hope. Most in the mainstream media have refused to cover the truth about the murder.

With luck and continuing public scrutiny, this Washington Post initiative will hopefully extend to others in the mainstream media.