Above Photo: President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at the White House, January 28, 2020. (Photo: Koby Gideon/GPO)

After being announced shortly after Donald Trump took office in 2017, the “Plan” (modestly called “the Vision”) supposed to put an end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was made public on January 28th. It is therefore now possible to analyse its substance in detail, deepening the reflections that have already been made on the basis of the leaks of some of its aspects. The United States had already adopted a series of decisions and measures which suggested that the definition of the parameters supposed to bring a definitive solution to the conflict would largely espouse Israeli positions: recognition of Jerusalem as the indivisible capital of the State of Israel, closure of the office of the Palestinian delegation in Washington, cessation of funding for UNRWA (the United Nations agency for Palestinian refugees) and, most recently, recognition of the legality of Israeli settlements installed on Palestinian territory. A thorough reading of the “Plan” in all its aspects only reinforces this presentiment, as it appears that the proposals it contains support the main Israeli demands, setting aside the internationally recognised rights of the Palestinian people. Generally speaking, the “Plan” appears to enshrine the existing situation on the ground, consolidating the occupation and Oslo regime by changing its label only. In the following lines, the main aspects of the “Plan” are analysed, showing how it departs diametrically from the principles established by international law and that the creation of a Palestinian State, presented as a major step forward in the proposed solution, would only be virtual, the envisaged Palestinian entity being devoid of the essential prerogatives of sovereignty.

1. The exclusion of international law from the parameters of the solution to the conflict

In the preamble of the “Plan”, a position is taken which results in the exclusion of the whole of international law, as derived from UN resolutions and a range of other texts, as the essential basis for establishing the parameters of the solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It reads as follows:

“Since 1946, there have been close to 700 United Nations General Assembly resolutions and over 100 United Nations Security Council resolutions in connection with this conflict. United Nations resolutions are sometimes inconsistent and sometimes time-bound. These resolutions have not brought about peace. Furthermore, different parties have offered conflicting interpretations of some of the most significant United Nations resolutions, including United Nations Security Council Resolution 242. Indeed, legal scholars who have worked directly on critical United Nations resolutions have differed on their meaning and legal effect.

While we are respectful of the historic role of the United Nations in the peace process, this Vision is not a recitation of General Assembly, Security Council and other international resolutions on this topic because such resolutions have not and will not resolve the conflict. For too long these resolutions have enabled political leaders to avoid addressing the complexities of this conflict rather than enabling a realistic path to peace”.

Indeed, the rest of the Plan will no longer mention UN resolutions as a basis or justification for the proposed solutions, with the exception of a furtive reference to Security Council Resolution 242, whose Israeli interpretation, which is in favour of only a partial withdrawal from the territories occupied since 1967, albeit isolated, will be adopted to justify the annexation of a substantial part of the West Bank by Israel (see below). However, any peace process as previously envisaged by the United Nations or by the United States itself was based on the need to implement resolutions 242 and 338 in order to reach a settlement of the dispute, and the International Court of Justice concluded its 2004 opinion on the legality of the Wall by stating that “any negotiated solution” for the establishment of a Palestinian state must be “on the basis of international law”. In reality, and contrary to what the “Plan” claims, the UN resolutions do indeed establish all the principles that should guide the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict:

– right to self-determination of the Palestinian people

– Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem as “occupied Palestinian territories”.

– illegality of Israeli settlements in Palestinian territory

– illegality of the annexation of East Jerusalem

– Israel’s obligation to withdraw from the territories occupied in the June 1967 war

– the right of all states in the region to live within secure and recognised borders

– Palestinian refugees’ right to return to their homes or right to fair compensation

As will be seen, the “Plan” does not apply, or even mention, any of these principles, and generally takes the opposite view in defining the criteria for resolving the main points of dispute, based on two elements that will be overriding: Israel’s security concerns and the recognition of its “valid legal and historical claims”.

2. The determination of the borders: validation of the annexation and the settlements

The territorial question and the determination of the borders between the State of Israel and a State of Palestine is a fundamental aspect of the conflict. Since 1967 and the conquest of Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem, Israel has pursued a policy of annexation (de jure or de facto), resulting in the colonisation and fragmentation of Palestinian territory, policies declared illegal by numerous United Nations resolutions, the most recent being resolution 2334 adopted by the Security Council in December 2016. The “Plan” provides for the annexation by Israel of approximately 30% of the West Bank, including almost all of the existing settlements and a large part of the Jordan Valley. Among the criteria set out as the basis for this border delineation are the “security requirements of the State of Israel”, as well as “its “valid legal and historical claims”. The solution is justified by the “Plan” as follows:

“The State of Israel and the United States do not believe the State of Israel is legally bound to provide the Palestinians with 100 percent of pre-1967 territory (a belief that is consistent with United Nations Security Council Resolution 242). This Vision is a fair compromise, and contemplates a Palestinian state that encompasses territory reasonably comparable in size to the territory of the West Bank and Gaza pre-1967”.

Here is the only reference to international law made by the “Plan”, reflecting the interpretation that Israel and the United States have given to it, whereas the most consistent reading, shared by the vast majority of the international community, is that resolution 242 implies withdrawal from all the territories occupied by Israel in 1967, in accordance with the principle of non-acquisition of territory by force, recalled in the preamble to the resolution. The “Plan” goes so far as to consider that the allocation of territory for a Palestinian State is in fact a “significant concession” on the part of Israel, since Gaza and the West Bank have been conquered “in a defensive war”, that Israel has already withdrawn from 88% of all the Arab territories captured in 1967 (mainly the Egyptian Sinai), and that the remaining areas are part of “the ancestral homeland of the Jewish people”, over which Israel has asserted “valid legal and historical claims”. The “Plan” claims that the new route “encompasses a territory reasonably comparable in size to the territory of the West Bank and Gaza before 1967”. In reality, the West Bank is being reduced by a substantial part of its surface area, including the most fertile part, the Jordan Valley, which is compensated quantitatively only by the addition of small portions of land adjacent to the West Bank and by the granting of two areas west of the Negev Desert to be linked to Gaza by road corridors. In addition, Israel is expected to “retain” sovereignty over Gaza’s territorial waters on the grounds that they are supposed to be “vital to Israel’s security”.

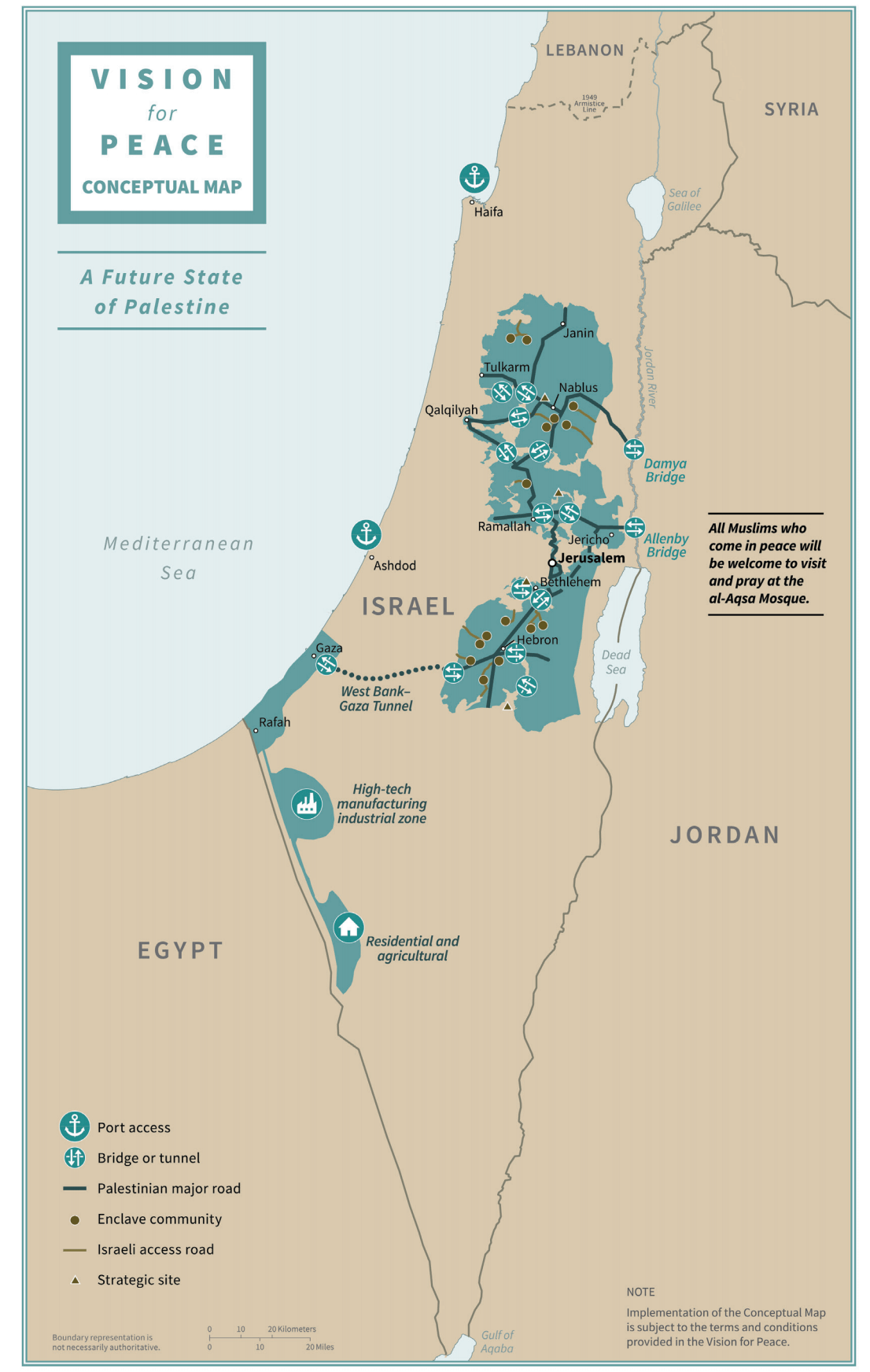

Map of a future Palestinian state in the Trump administration plan.

In sum, in view of the map annexed to the “Plan” (see above), the West Bank would appear as a set of fragmented islands, perforated by Israeli enclaves formed by the settlements, linked together by a very complex road system, totally subjected to Israel’s security responsibility. The West Bank itself would also be enclaved in Israeli territory, with no contiguity with the Jordanian border and no access to the waters of the Jordan River or the Dead Sea. The “Plan” thus has the effect of validating all the Israeli settlements, ignoring their illegal character under international law, and attributes the Jordan Valley to Israel on the grounds that this region is “essential for Israel’s national security”, without taking into account its status as “occupied Palestinian territory” or the principle of non-acquisition of territory by force. It is therefore in complete disregard of international law that the borders have been drawn in the plan devised by the US Administration.

3. The status of Jerusalem: confirmation of the Israeli annexation

In line with the recent positions adopted by the Trump administration, the “Plan” confirms that Jerusalem remains the indivisible capital of the State of Israel. By a semantic game, the “Plan” announces that the capital of the Palestinian State will also be located in Jerusalem, but in reality it would include only a few Arab neighbourhoods and villages already separated from the city by the Wall built by Israel, and the peripheral city of Abu Dis:

“Jerusalem will remain the sovereign capital of the State of Israel, and it should remain an undivided city. The sovereign capital of the State of Palestine should be in the section of East Jerusalem located in all areas east and north of the existing security barrier, including Kafr Aqab, the eastern part of Shuafat and Abu Dis, and could be named Al Quds or another name as determined by the State of Palestine”.

Once again, this is a total rejection of one of the fundamental demands of the Palestinians, inherent in their national claims, and a confirmation of the Israeli annexation, although condemned by several United Nations resolutions, which declared it “null and void” and referred to East Jerusalem as “Palestinian territory”.

4. The creation of a State of Palestine devoid of any effective sovereignty

The supposedly most favourable contribution to the Palestinians, and the main Israeli concession, is the creation of a Palestinian state, reflecting “the legitimate desire to govern itself and to chart its own destiny”. Upon analysis, it appears that the Palestinian entity envisaged by the “Plan” has very few of the characteristics of a State and cannot seriously be considered as the genuine implementation of the right to self-determination. From the outset, the “Plan” makes things clear:

“Sovereignty is an amorphous concept that has evolved over time. […] The notion that sovereignty is a static and consistently defined term has been an unnecessary stumbling block in past negotiations. Pragmatic and operational concerns that effect security and prosperity are what is most important”.

And indeed, the State of Palestine as conceived by the “Plan” is so limited in its powers that it can hardly be considered as possessing the attributes classically associated with the concept of sovereignty. It is not possible to go into all the details of the “Plan” here, but here are some illustrations of the very substantial limitations that would affect the Palestinian State. First, entry into the Palestinian territory will be done exclusively through Israeli control posts, whether at the Jordanian border, via Israeli territory (annexation of the Jordan Valley), or Egyptian, via Gaza. The “Plan” states unambiguously in this regard: “All persons and goods will cross the borders into the State of Palestine through regulated border crossings, which will be monitored by the State of Israel”. Then, Israel will exercise operational control of all Palestinian airspace for security reasons and will have sovereignty over Palestinian territorial waters. Finally, Israel will have the ultimate prerogatives for all security issues in Palestinian territory. As the “Plan” states: “Upon signing the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Agreement, the State of Israel will maintain overriding security responsibility for the State of Palestine, with the aspiration that the Palestinians will be responsible for as much of their internal security as possible, subject to the provisions of this “Vision” “. To implement this prerogative, Israel will have the right to use “blimps, drones and similar aerial equipment for security purposes”. The use of such equipment is intended to “reduce the Israeli security footprint within the State of Palestine”, which implies that ground military interventions will also be possible. Israel will also maintain its security jurisdiction over the entire road network linking Palestinian and Israeli enclaves, and over constructions on Palestinian territory “in the areas adjacent to the border between the State of Israel and the State of Palestine, including without limitation, the border between Jerusalem and Al Quds”. It should also be pointed out that the Palestinian State will not have sovereign authority over national immigration on its own territory, since the return of Palestinian refugees would be subject to numerous restrictions, depending on Israeli consent (see below).

To all these limitations must be added the fact that the State of Palestine could come into being only after fulfilling many preconditions in the matters of security, disarmament of Palestinian groups, governance and institutions. Whether all the conditions have been met will be subject to review by Israel and the United States.

5. The Palestinian refugee problem: rejection of the right of return and the right to compensation

Another central aspect of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the issue of Palestinian refugees, who have been expelled or had to flee their homes as a result of the 1948 or 1967 war. There are now several million of them, scattered all over the world, particularly in the Arab states, the West Bank and Gaza. United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, adopted in 1948 and reiterated many times, established a right of return by resolving “that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible”.

Any exercise of a return of Palestinian refugees to their homes, now located in Israel, is precluded by the “Plan”, and even a return to the State of Palestine is subject to a series of restrictions. No right to compensation is enshrined, and no mention is made of Israel’s responsibility, its primary role in the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem being overlooked. On the contrary, it is the Arab states that are held responsible for the persistence of the situation. This general approach is explained by the “Plan” as follows:

“The Palestinians have collectively been cruelly and cynically held in limbo to keep the conflict alive. Their Arab brothers have the moral responsibility to integrate them into their countries as the Jews were integrated into the State of Israel. […] Proposals that demand that the State of Israel agree to take in Palestinian refugees, or that promise tens of billions of dollars in compensation for the refugees, have never been realistic and a credible funding source has never been identified”.

The “Plan” therefore concludes that “there shall be no right of return by, or absorption of, any Palestinian refugee into the State of Israel.” Three options are then possible: absorption in the Palestinian State, local integration in current host countries, or resettlement (with a maximum of 50,000 refugees) in one of the member countries of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. It should be pointed out, as already noted above, that the return of refugees to Palestinian territory would be subject to serious restrictions, depending on Israel’s consent: Palestinians from countries “extremely hostile” towards the State of Israel would be subject to a special procedure through a joint Israeli-Palestinian committee which would analyse the security issues. More generally, for all Palestinian refugees, the volume of immigration would have to be agreed between the parties and regulated by various factors, “including economic forces and incentive structures, such that the rate of entry does not outpace or overwhelm the development of infrastructure and the economy of the State of Palestine, or increase security risks to the State of Israel”.

On the issue of compensation for property lost as a result of Palestinian exile, no rights are formally recognized. The “Plan” simply states that priority will be given to financing the political and economic structures of the State of Palestine, which will indirectly benefit the returning refugees, and that in order to allow certain individual compensations, the United States will “endeavour to raise a fund”, whose sources of funding and mechanism remain unclear at this stage. In any case, this is not an accountability mechanism, involving the State of Israel.

Conclusions

It is absolutely obvious that the “Plan” published by Donald Trump consists mainly of a validation of the occupation and settlement policies pursued by Israel on the ground, considered illegal by multiple UN resolutions and by the overwhelming majority of states. In reality, it is a perpetuation of the occupation and the Oslo system under another name, with Israel keeping in its hands the essential elements of the administration of the Palestinian territories and the population residing there. The State of Palestine that would be created would be largely fictitious, with no control over its borders, its security and its population, with a completely fragmented and shrinking territory, losing East Jerusalem and the Jordan Valley, taking the 1967 lines as a reference. The West Bank would become landlocked with Israeli territory, losing its border with Jordan, making it particularly dependent on the goodwill of the State of Israel, both for the movement of people and goods. The logic of the “Plan” is reminiscent of the Bantustan policy implemented by the South African apartheid regime from the end of the 1970s, which artificially created fictitious, supposedly independent states in which most of the black population was confined, thus justifying their exclusion from the South African political system. Under the Trump Plan, Israel, as today, will de facto control the entire territory of historic Palestine, but without having to grant any political rights to the Palestinian population residing in the so-called “State of Palestine”.

The “Plan” obviously has no chance of being accepted or even discussed by the Palestinians, as it constitutes a denial of their basic rights. Nevertheless, it has been understood by the Israeli government as a green light for the formalization of the annexation of the Jordan Valley and the settlements. It is also further proof of the contempt expressed by the Trump administration for respect for the most fundamental rules of international law and multilateralism.