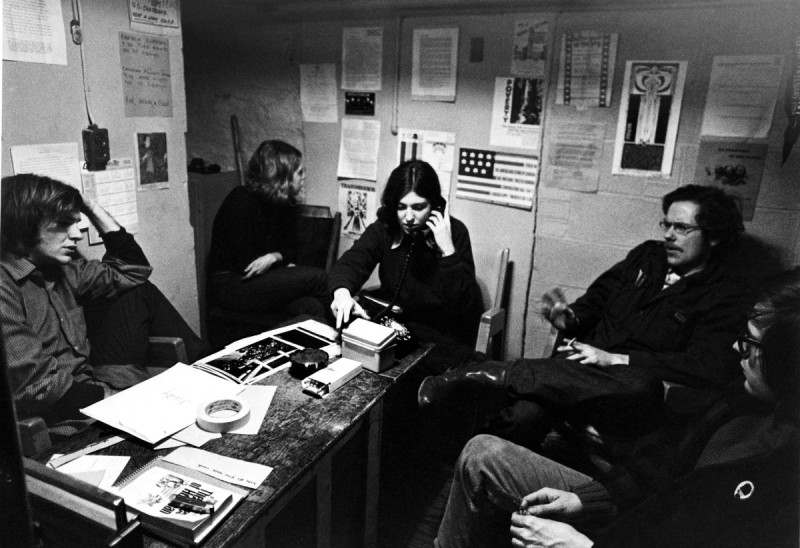

Above photo: Draft-age Americans being counselled by Mark Satin (far left) at the Anti-Draft Programme office on in Toronto, 1967. The Anti-Draft Programme was Canada’s largest organization providing emigration counselling and services to American Vietnam War resisters. Laura Jones / Wikimedia Commons.

A powerful look back at the Americans who defied the draft during the Vietnam War.

And the Canadian refuge that welcomed them.

When the United States was carrying out its genocidal campaign against Vietnam in the 1960s and 70s, Canada welcomed tens of thousands of American war resisters to this country. Their actions, along with peace movements in the US and around the world, not only helped to end the war, but they may have even forced President Richard Nixon to abandon a plan to escalate the conflict with the use of tactical nuclear weapons.

In light of the serious challenges we face today—including the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, rising poverty and inequality, and the deepening environmental crisis—it is more important than ever to remember, and draw inspiration from, the millions of Americans who resisted the US war in Vietnam, as well as in Cambodia and Laos. Just as importantly, we must remember the meaningful victories won by these peace movements.

The first occurred during Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, when he asked the Pentagon whether sending an additional 200,000 US troops to Vietnam—on top of the 500,000 already deployed—would lead to victory. Crucially, the generals responded that they didn’t know if it would make a difference. What they did emphasize, however, was that those troops were needed at home to confront the growing power of the antiwar resistance.

Even more significantly, during Richard Nixon’s presidency, he and Henry Kissinger seriously considered using nuclear weapons against Vietnam. They openly acknowledged that it didn’t matter how many millions might be killed—but ultimately decided against it, fearing the backlash it would provoke both in the United States and internationally.

A major obstacle to the US war effort in Vietnam was the widespread resistance by millions of Americans. This took many forms: mass demonstrations, teach-ins, support for GIs and draftees, campus and workplace occupations, and more. In a powerful moment in Washington, DC, 800 members of Vietnam Veterans Against the War publicly discarded the medals they had been awarded. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of men and women refused to serve, whether through draft resistance or desertion. Without question, these acts of defiance played a crucial role in preventing the US from escalating the war even further.

In recognition of the importance of this resistance, Noam Chomsky dedicated his 1969 book, American Power and the New Mandarins, “To the brave young men who refuse to serve in a criminal war.”

In Hell, No! We Didn’t Go! Firsthand Accounts of Vietnam War Protest and Resistance, lawyer and resister Eli Greenbaum shares the stories of dozens of young men who “[refused] to serve in a criminal war.” He estimates that over 300,000 Americans either resisted the draft or deserted, and that 30,000 to 50,000 fled to Canada. Many of them chose to remain even after being offered presidential amnesty. According to Greenbaum, none of the men he spoke with “expressed regret for not going.”

In his own case, Greenbaum sought help from a psychiatrist in hopes of qualifying for an exemption. “He responded by telling me that he felt I was a rational, mature, adult male and, therefore, completely unsuitable for the draft,” Greenbaum recalls. “He said he would be happy to write a strong disqualifying letter.” It worked. Still, he remained troubled by those who didn’t have the resources or knowledge to avoid conscription. “What happened to the kids who didn’t know their options or outs, the kids with no money who would wind up serving as cannon fodder…?” he asked.

Perhaps the most famous draft resister was three-time boxing champion Muhammad Ali. For refusing to fight in what he saw as an unjust war, Ali was arrested, convicted, stripped of his heavyweight title, and sentenced to five years in prison (the US Supreme Court later overturned the conviction in a unanimous 8–0 decision).

Greenbaum’s outrage deepened as he learned more about the war itself, including the revelation that the supposed trigger for escalation—the “Gulf of Tonkin” incident, in which North Vietnamese forces allegedly attacked a US destroyer—was a fabrication (much like the later claims about Iraq’s “weapons of mass destruction”). One result of this manufactured crisis was that the US dropped “more bombs on North Vietnam than were dropped on all of Europe during World War II.”

Another resister, Tom, initially supported the war. “I’m gonna join the Marines and get the Commies!” he declared. But after enrolling at the University of San Francisco and engaging more critically with US foreign policy, his views began to change. In 1967, facing the draft, he fled to Vancouver. There, he earned a degree from the University of British Columbia, trained as a therapist, and later became a freelance journalist.

Leo, another young man, was a full-time university student when he was classified 1-A—eligible for immediate induction. At just 18 and unaware of his right to appeal, he found himself in the military and ordered to deploy to Vietnam. By then, having learned more about the war’s illegality, he decided to flee to Canada. One night, while driving with his father, they noticed a police car trailing them. Leo’s father, a Second World War veteran, turned to him and said, “Don’t worry. If they’re after you, I’ll outrun them.” Fortunately, the police didn’t pursue them, and a few days later, Leo successfully crossed into Canada. Years later, when he was granted Canadian citizenship, the presiding judge told him, “We’re happy to welcome people like you to our country.”

Resistance also came from within the military. There were hundreds of cases in which US infantry units refused orders or negotiated informal ceasefires with Vietnamese guerrillas: “We won’t go after you if you don’t attack us.”

Though it took far too long—and at the cost of over three million lives—the nonviolent resistance to the Vietnam War, both at home and within the ranks of the military, played a crucial role in ultimately ending the slaughter.

Importantly, Canadians overwhelmingly supported the American war resisters who made their way to the “True North.”

Peter G. Prontzos is a writer and Professor Emeritus of Political Science and Interdisciplinary Studies at Langara College, Vancouver.