Above illustration: Lincoln Agnew.

NOTE: This article lays out the harmful impacts of medical debt and ways to deal with it. The problem with the solution proposed is that it exists within the framework of the unjust healthcare system we have. Medical debt doesn’t need to be “relieved,” it needs to be abolished. The United States spends twice as much per person per year on healthcare as the other wealthy nations and those nations have universal systems that treat health care as a public good, not a profit-making venture. The US could move quickly to national improved Medicare for all and end medical bills altogether. That is what we need to be fighting for. – MF

That debt doesn’t just hurt your bank account—it can harm your health, too.

What you must know now.

Devin Barrington-Ward was doubled over with stomach pain. His chest hurt, too. Though his family urged him to call an ambulance and he was terrified that his condition was serious, Barrington-Ward had another concern on his mind: the expense. Uninsured, he knew he couldn’t afford the ambulance ride.

So his mother raced him to a hospital near his home in suburban Atlanta that day in January earlier this year. After several hours in the emergency room, where he saw numerous physicians and got a CT scan and other tests, Barrington-Ward was diagnosed with colitis. Not long after came the bill: almost $10,000. Though his health is better today, he says he’s still saddled with debt, and the side effects of that are significant.

For one thing, it means juggling priorities. He just started getting a social justice organization he founded, the Black Futurists Group, off the ground. “I’m in the critical years of my plan,” says Barrington-Ward, who is 30. “I want to have a family and own a home.” But now, he says, he has to balance the debt with making investments in himself, his work, and his future.

Barrington-Ward is not alone. The pain of medical debt is especially pronounced in Black and Hispanic communities, according to a June 2020 Consumer Reports nationally representative survey of 1,267 U.S. adults who had a medical bill that they had to pay out of pocket.

But it’s a problem for many, and a uniquely American one. People in Canada, Australia, the U.K., and many other countries who have the misfortune of getting sick don’t face the same risk of massive bills in the aftermath, according to the Commonwealth Fund, a healthcare research group. Those countries generally offer free or low-cost healthcare to all citizens.

In this country, though, illness is not so easily recovered from, at least financially. More than a quarter of American consumers have debt that’s been turned over to collections, with over half of that from medical bills, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The amount of medical debt sent to collection agencies was estimated to be $81 billion, according to a 2018 study published in Health Affairs. Medical debt is also a top reason that people file for bankruptcy, according to a 2019 article in the American Journal of Public Health.

Even relatively small amounts of medical debt can trigger a cascade of other financial problems, according to CR’s recent survey. Among the respondents: a 66-year-old Tennessee resident who said he had to dip into his grandchildren’s college savings fund and a 23-year-old Montana man who had his wages garnished, both to pay medical bills that were less than $2,000. Or there’s the 57-year-old Californian who said he had to sell his truck to cover a medical bill of less than $1,000.

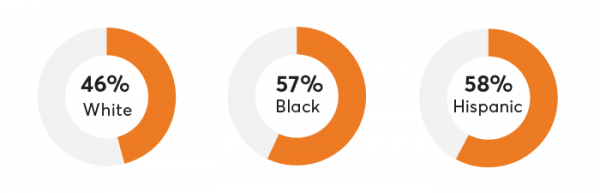

To make matters worse, medical debt can harm not only your financial health but also your physical health. One way is by causing you to delay needed medical care. In CR’s survey, 41 percent of people said they put off a doctor’s visit because of cost. But research shows that the emotional toll of medical bills can also harm health by triggering chronic stress, which is linked to a host of health problems and even premature death.

And the situation threatens to get much worse. The Kaiser Family Foundation, a health research group, estimated in May that up to 27 million Americans could lose their employer-based health insurance as a result of the pandemic.

“The U.S. has reached a tipping point,” says Ida Rademacher, executive director of the Financial Security Program at the Aspen Institute, a research and policy organization. Even before the crisis, she says, American households were financially fragile.

Now, worsening money and health-coverage problems will coincide with the need of hospitals and medical systems to collect on their debts. “This will continue to add to levels of stress and behaviors like delaying medical care,” she says.

“Millions of people are living paycheck to paycheck,” says Ray Kluender, at the Harvard Business School and the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, where he studies medical debt. “They don’t have the buffer to deal with the shock of a medical bill.”

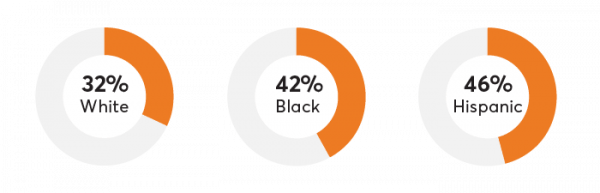

How High Healthcare Costs Affect Americans: A burden felt unequally

Americans who say they are very or extremely concerned about being able to pay for needed medical care

Americans who say they are very or extremely concerned about being able to afford their medical bill with the highest out-of-pocket cost

Americans who say they were surprised by their medical bill with the highest out-of-pocket cost

Americans who say they are very or extremely worried about their family’s access to affordable health insurance

Big Medical Bills Lead to Cost-cutting choices

To save on healthcare in the last 12 months:

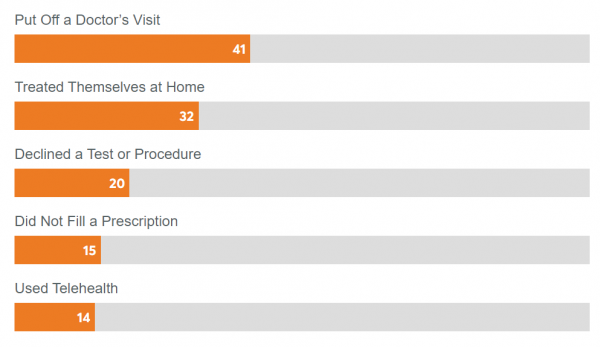

The Financial Ripple Effects

To pay for medical care costs in the last 12 months:

Among the types of debt a person might have, medical debt is unique. Consumers—even those with health insurance—have little control over how medical debt is incurred, says Francis Wong, a fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research who studies how medical debt affects people’s lives.

For one thing, when it comes to buying healthcare services, you usually can’t comparison shop. “Healthcare is simply not like other consumer goods,” Wong says. “It isn’t shoppable.”

For another, as Barrington-Ward can attest, medical debt often arises not from purchases we choose to make—like buying a house or car—but from illnesses and injuries that strike us, often unexpected and unavoidable.

And having insurance doesn’t always protect against unexpected charges. People can be hit with surprise medical bills for care not covered by insurance. In CR’s survey, fully half of people, when asked to think about their most expensive bill of the past year, said they didn’t know in advance it was coming.

Retired school teacher Patricia Hedgepeth, from Lathrup Village, Mich., is one such person. Her husband became ill in 2017, and though insured through her former job, by the time he died in January of this year, the family had accrued more than $16,000 in medical bills. “I still don’t know what any of those bills were for,” Hedgepeth says.

Big bills not covered by insurance can also arrive suddenly if you are among the tens of millions of Americans with a high-deductible health plan. Such plans require that individuals pay at least $1,400 out of their own pocket and families pay $2,800 before insurance kicks in. CR’s survey found that deductibles were the most common cause of high out-of-pocket costs, with 43 percent of people saying their highest medical bill in the last 12 months was due to the requirement to meet a deductible.

And then there is the medical bill itself, a confusing list of codes for providers and services, up to half of which are wrong, duplicating charges or billing for procedures you didn’t have or doctors you didn’t see, says Caitlin Donovan, senior director of the Patient Advocate Foundation, which helps consumers fight billing problems. The result? Unless you catch it, you wind up spending even more on your healthcare than needed.

That’s what happened to Phyllis Vance, 59, from Indianapolis, who participated in a national panel of consumers discussing healthcare costs for CR and said she was billed erroneously for a medical service. “I had to call the billing department several times before they realized they’d made an error,” she says. “It took about a month and a half to get it cleared up.”

That doesn’t surprise Donovan. She says it takes case managers at the Patient Advocate Foundation an average of 22 phone calls to resolve each client’s billing problems. “The system is designed to make you want to give up and just pay,” she says.

The effects of medical debt can quickly spread to other areas of your life.

Thomas Draper of Atlanta says that while being treated for lung cancer a decade ago, he had to switch jobs, and the insurance offered by his new employer didn’t cover the cancer hospital where his doctors work. Though his cancer is now in remission, he struggles to pay for his annual imaging tests. The stress in his home over that debt took an emotional toll, he says. “Medical bills definitely contributed to my divorce,” says Draper, who was married for 13 years until he and his ex separated three years ago.

Other consumers, too, describe lives changed and dreams deferred because of medical debt. Another CR panel member, Stacie May from Minot, Maine, spoke of money earmarked for a house down payment that went to medical debt.

In too many cases, unmanageable medical debt causes what Rademacher calls a financial snowball effect, with one bad financial outcome leading to another, digging people into ever deeper holes.

One particularly painful outcome: when unpaid debt is sent to collections. That can lower a person’s credit score, which can make access to future credit harder or more expensive, undermining the ability to buy a car or house, or even rent an apartment.

That’s what Nikiesha Barnett of Raleigh, N.C., says happened to her last year. When she tried to sign a lease for an apartment large enough so that her mother could move in with her, she learned her credit had taken a hit because of one unpaid medical bill for less than $1,200. “I had other bills from the surgery that I paid, but this one was just unmanageable,” she says.

Barrington-Ward, the Atlanta activist who has experienced his own problems with medical debt, says such problems hit Black Americans especially hard, worsening inequities that have undermined their ability to build wealth for generations.

The Urban Institute estimated that in 2015 almost 1 in 3 Black adults had past-due medical bills, compared with 1 in 4 for all populations combined.

That could lead to higher rates of worry: When asked how concerned people were with being able to pay for medical care, 45 percent of Blacks and 48 percent of Hispanics said they were “extremely” or “very” concerned, compared with 32 percent of whites.

Financial Stress Can Make You Sick

Regardless of race, medical debt is emotionally draining. And the resulting stress is more than just annoying: It can be harmful to one’s health.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, research has linked high-debt stress to ulcers, digestive problems, and impaired sleep. But chronic stress over money might affect health in less obvious, even more serious ways. The connection is so concerning that two regional Federal Reserve banks—in San Francisco and Atlanta—have looked at how medical debt impacts the health of U.S. citizens.

The San Francisco review, citing previously published medical research, noted that adrenaline and cortisol released by the body in response to chronic stress linked to finances can elevate blood pressure and heart rate, and impair memory and immune function.

In an even more robust 2016 analysis, the Atlanta study used credit histories to link high debt loads and debt delinquency with mortality. In other words, the bigger a person’s unpaid debt, the higher their risk of dying early. Further, they found that a 100-point improvement in a person’s credit score is associated with a 4 percent decline in their risk of death.

How to Fight Big Medical Bills

Medical debt can appear on your credit history in as little as 180 days. You can avoid that by addressing medical bills as soon as they arrive. If you plan to take any action that could take extra time, notify the hospital or doctor’s office right away and ask for a 30-day extension.

Don’t automatically pay. Hospitals and doctor’s offices may send bills to patients before they file with insurers, says Caitlin Donovan of the Patient Advocate Foundation. So if you’re insured, wait until you get an “Explanation of Benefits” from your insurer that breaks down what it will cover and what you’ll owe. If you still have questions, contact your insurer.

Get an itemized bill. If the amount due seems high or is unaffordable, ask your insurer for an itemized list of each charge, Donovan says. Look for duplicate charges or charges for procedures, tests, or services you did not receive. Report errors to your insurer and the hospital or doctor’s office.

Compare prices. For legitimate charges, ensure you aren’t being billed too much by comparing what your doctor or hospital charged vs. industry standards. To find those amounts, go to healthcarebluebook.org. Report over-charges to your insurer and the hospital or doctor’s office.

Ask for an exception. For bills not covered by your health plan, ask your doctor to contact the insurer explaining why the care was needed and should be covered. Your doctor should include your diagnosis, why other treatments were stopped, and other details from your medical history.

Negotiate. If you can’t get an exception, see whether the hospital or doctor will lower what you owe. One approach: Offer to pay immediately. The Advisory Board, a healthcare research firm, says some providers offer sizeable discounts for paying right away.

Request a payment plan. Many hospitals will do this, typically charging interest rates lower than many credit cards. Not using your credit card may provide another benefit: Several states have passed laws limiting how quickly medical bills not on credit cards can be given to collection.

Seek outside help. Look for a medical billing specialist through the Alliance of Professional Health Advocates (advoconnection.com). Or consider hiring an attorney, something 23 percent of people in CR’s survey said they did regarding a large medical bill.

Apply for charitable care. Many providers offer free or reduced rates to people who qualify because of low incomes or other reasons. Renee Morgan, 48, of Vancouver, Wash., for example, took advantage of such a program after her husband suffered a mini stroke in April 2018 and was rushed to the emergency room, putting the family $19,000 in debt. To find a program, contact Dollar For, an organization that matches qualified individuals with debt forgiveness programs.

Big Bills, Less Care

The high cost of medical care also contributes to poor health by scaring people away from needed care. In CR’s survey, 20 percent of Americans who had received a medical bill with out-of-pocket costs declined to have a test or procedure because of the expense, and 15 percent didn’t fill a prescription.

High deductibles pose particular barriers. A 2019 Health Affairs study of almost 600,000 low-income women found that those who developed breast cancer and had deductibles of $1,000 or more waited an average of 8.7 months longer to start chemotherapy compared with women who had deductibles of $500 or less.

Of course, healthcare is often put off because of a lack of any health insurance at all, a problem that impacts people of color most. And access to healthcare is worse in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, as many states in the south, which have large Black populations, have failed to do, Aspen Institute’s Rademacher says.

Delaying medical care can mean getting sicker, according to a 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation survey. It found that of the half of U.S. adults who said they or a family member put off some sort of dental or other healthcare in the past year because of cost, 1 in 8 said their medical condition worsened as a result.

The high cost of healthcare is such an impediment that in January the American College of Physicians called for an end to high deductibles for low-income people and those with special needs. If there must be one, the ACP wants cost-sharing reduced or eliminated for important services so that more people have access to care without the concern over cost.

Getting Help

Patricia Hedgepeth, the Michigan teacher, got some assistance from the Patient Advocate Foundation. A case manager there helped her negotiate her $16,000 bill down to $2,500. “I’m not sure what I would have done without them,” she says.

And earlier this year, both Draper, the Atlanta cancer survivor, and Barnett, the North Carolinian who struggled to find an apartment, got help from an unexpected source. They received letters from RIP Medical Debt, a nonprofit that uses donations to pay off overdue medical bills from collection agencies.

Both were told that their debt had been forgiven. “During the pandemic and everything that was going on, it was like somebody had my back for once,” Draper says. Barnett, who had the delinquent bill removed from her credit report, was equally relieved. “There are no words to describe how happy I was,” she says.

Though most people can’t rely on RIP Medical Debt to save the day, there are a number of other solutions people can turn to now to get help. (See “How to Fight Big Medical Bills,” above.)

Equally important are legislative efforts to protect consumers, says Chuck Bell, programs director of advocacy at Consumer Reports. One partial solution in the works is legislation, recently introduced in Congress, called the Medical Debt Relief Act, which would keep any unpaid medical bills off a person’s credit report for a year. Another is legislation to ban surprise medical bills, which Bell says is currently pending before Congress.

Such systemic fixes would go a long way to protect consumers, improving their financial and even physical health, Rademacher says. “No one wants to make the choice between paying down medical debt or paying their rent.”