Above Photo: Brazilian Justice Minister Sergio Moro. Illustration: João Brizzi and Rodrigo Bento/The Intercept Brasil; Photo: Marcelo Camargo/Agência Brasil

An enemy of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro with close ties to Brazilian prosecutors published leaked videos of depositions on the eve of gubernatorial elections.

BRAZILIAN PROSECUTORS PLOTTED to leak confidential information from the Car Wash corruption probe to Venezuelan opposition figures at the suggestion of Justice Minister Sergio Moro, then the presiding judge for the investigation. The private conversations revealing the plotting, which took place over the Telegram chat app beginning in August 2017, indicate that the prosecutors’ motivation was expressly political, not judicial: They discussed the release of compromising information about the Venezuelan government of Nicolás Maduro, which had just taken steps to reduce the power of opposition politicians and removed the country’s prosecutor general, a Maduro critic and ally of the Car Wash prosecutors.

“It may be the case to make the Odebrecht deposition about bribes in Venezuela public. Is it here or with the PGR [Public Prosecutor]?” Moro wrote to Deltan Dallagnol, the coordinator of the Car Wash investigation, on the afternoon of August 5. Odebrecht is a Brazil-based construction company whose multinational, multibillion-dollar corruption scheme had been cracked open by the investigation.

Dallagnol replied hours later, outlining their options: “It can’t be made public simply because it would violate the agreement, but we can send spontaneous information [to Venezuela] and this would make it likely that somewhere along the way someone would make it public.” Dallagnol continued: “There will be criticism and a price, but it’s worth paying to expose this and contribute to the Venezuelans.”

Deltan Dallagnol at a National Association of Tax Auditors of the Federal Revenue of Brazil seminar in São Paulo on Aug. 1, 2018.

Deltan Dallagnol at a National Association of Tax Auditors of the Federal Revenue of Brazil seminar in São Paulo on Aug. 1, 2018.

Photo: Suamy Beydoun/AGIF via AP

The Car Wash prosecutors had frequently discussed leaking directly to the then-deposed Venezuelan prosecutor general, an equivalent position to an American attorney general. In the coming months, the deposed Venezuelan prosecutor general took to her blog and published secret evidence from the Car Wash case — a video of a deposition carried out by Brazilian investigators that was said to be in the hands of only the Brazilian prosecutors — on the eve of an important election.

A secret plot to leak information that would harm a foreign government is clearly outside of the mandate of the Brazilian Public Prosecutor’s Office — or a low-level federal judge.

The revelations of the discussion, published in partnership with the Folha de S.Paulo newspaper, come from an archive of documents provided exclusively to The Intercept Brasil by an anonymous source (read our editorial statement here). Previous revelations from the archive have rocked Brazilian politics. The exchange between the judge and the prosecutor is one of many such conversations revealed by The Intercept suggesting that Moro overstepped his role as a judge to act as the de facto leader of the Car Wash task force, a level of coordination which is illegal under Brazilian law.

The Car Wash probe began as a money laundering investigation in 2014, but it quickly became apparent that the initial targets were working on behalf of executives with the Brazilian energy giant Petrobras. The executives were demanding kickbacks to approve overinflated contracts and giving a cut of the kickbacks to politicians. More than five years later, the case has led to 244 convictions, 184 state’s witnesses agreements, and $3.4 billion in recovered assets; it revealed alleged corruption in 36 countries, mostly in Latin America. In almost all of these countries, local prosecutors signed agreements with the Brazilian Public Prosecutor to share information and pursue their own prosecutions. At least 13 current or former presidents have come under investigation, including Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was twice convicted on corruption-related charges.

Yet Moro and the Car Wash task force’s methods and impartiality have been called into question from nearly the beginning. Recent revelations from The Intercept put the operation’s domestic reputation in serious doubt. A Brazilian Supreme Court minister said in an interview that the reporting could be grounds to vacate convictions. Some of the Car Wash prosecutors’ foreign partners have privately raised concerns that abuses by Moro and Brazilian prosecutors could taint their own cases.

Moro declined to comment on the chat transcripts showing plotting to leak to Venezuelan opposition figures. He cast doubt on the authenticity of the messages obtained by The Intercept, but does not outright deny the chats — a reaffirmation of the position he has adopted in recent weeks. “Even if the alleged messages quoted in the report were authentic, they would not reveal any illegality or unethical conduct, only repeated violation of the privacy of law enforcement officials with the aim of overturning criminal convictions and preventing further investigations,” he wrote in a statement.

The Car Wash task force, based in Curitiba, the capital of the Brazilian state of Paraná, provided a similar response and would not comment on the specifics of the article. “The material presented in the article does not allow verification of the context and veracity of the messages,” they said in a statement.

“Our Actions Could Lead to More Social Upheaval and More Deaths”

The idea to leak information that could damage Maduro’s government came at an extremely tense moment for international relations with Venezuela. By July 2017, the U.S. had threatened Maduro with new sanctions if Venezuela proceeded with plans to found a Constituent Assembly — a new legislative body created to strengthen the government and undermine the opposition-controlled Congress. Maduro did establish the body, and a week later, President Donald Trump threatened military action — a first for a sitting U.S. president since Hugo Chávez became president of Venezuela in 1999, inaugurating 20 years of leftist rule in the country that frequently antagonized (and has been antagonized by) the U.S.

Meanwhile, the 2016 impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, the center-left president who followed Lula in office, marked a deterioration of relations between Brazil and Venezuela. Following the impeachment, Brazil’s new center-right government led the charge to have Venezuela suspended from Mercosur, a South American trade bloc. In December 2017, Venezuela expelled the Brazilian ambassador in Caracas and, days later, then-President Michel Temer reciprocated. The relationship hit rock bottom this January, when far-right Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro recognized Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guiadó as president and increasingly aligned his country with the U.S.

The unauthorized disclosure of confidential information by prosecutors could be a violation of Article 325 of Brazil’s criminal code, which allows for up to two years in prison for a public agent who “reveals a fact that they are aware of due to their position and that should remain secret, or facilitate its revelation.” And there were other risks, too: Odebrecht lawyers repeatedly complained to Brazilian prosecutors about leaks, saying that they could put lives at risk and compromise their ability to strike a deal with Venezuelan authorities — possibilities that the prosecutors acknowledged in internal chats as well.

The Car Wash prosecutors’ discussion about leaking information to damage Maduro’s government came in the wake of the shake-up to Venezuela’s system of governance. Just hours before Moro’s message suggesting a leak, the newly appointed Constituent Assembly, formed as a way to subvert the opposition-controlled Congress, gathered for its first full day of deliberations. In one of the body’s first moves, it voted to remove Luisa Ortega Díaz as prosecutor general, a post which she had held for nearly 10 years under Chávez and Maduro. Ortega had become an ally of the Car Wash investigation and, weeks earlier, she filed the first charges in a related case, indicting two Maduro allies for allegedly receiving bribes from Odebrecht. Her decision infuriated Maduro.

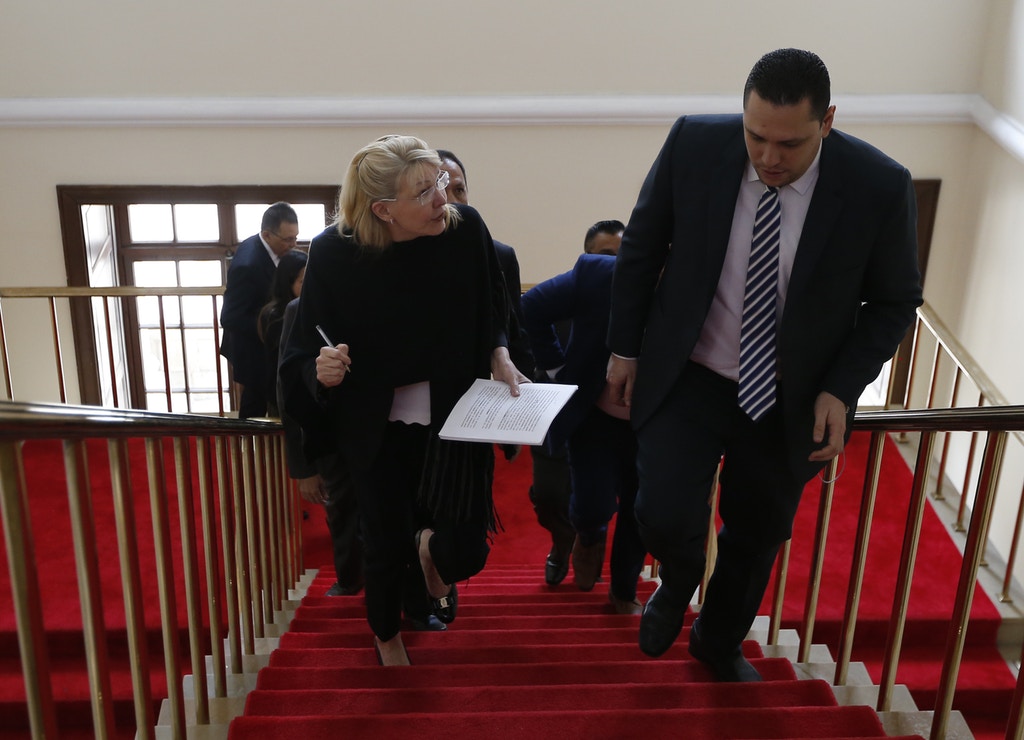

Venezuela’s ousted top prosecutor Luisa Ortega Díaz, left, arrives at the Colombian Congress in Bogota, Colombia, to address exiled members of the Venezuelan Supreme Court in a hearing against Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro for his alleged involvement in the Odebrecht corruption case, on August 15, 2018.

Photo: John Vizcaino/AFP/Getty Images

The Car Wash team had hoped that Ortega would reveal this information through the Venezuelan justice system but with her removal from office, that no longer seemed possible — at least not through the courts.

Under threat from the Maduro government, Ortega went into self-imposed exile and, after a stop in Colombia, flew to meet Brazil’s prosecutor general in the capital, Brasília, on August 22. The messages obtained by The Intercept show what she wanted: to cooperate with Car Wash even though she no longer had the authority of her former title. “We witnessed an institutional rape of the Venezuelan Public Prosecutor’s Office,” said Brazilian Prosecutor General Rodrigo Janot, alongside Ortega at a press conference in Brasília. “Without independence, the Public Prosecutor’s office of our northern neighbor is no longer able to … conduct criminal investigations or act in court with independence.”

Out of the spotlight, the task force had been discussing the subject of a possible leak intensely, debating whether the revelations would have potentially explosive consequences. “Realize that a civil war is possible there and any action by us could lead to more social upheaval and more deaths,” said Paulo Galvão, one of the Car Wash prosecutors, on August 5. His colleague Athayde Ribeiro Costa also demonstrated caution: “Imagine if we decide to do it and the madman orders the arrest of every Brazilian in Venezuelan territory.”

Dallagnol, the head prosecutor on the Car Wash task force, tried to assuage his colleagues’ fears, addressing Galvão by his initials. “PG, regarding risk, it’s something that is up to the Venezuelan citizens to ponder. They have the right to rebel,” Dallagnol wrote. He continued to lobby for action in Venezuela the following day:

August 6, 2017 – Filhos do Januario 2 group

Deltan – 14:48:25 – We have civil facts and we’re sharing them for criminal purposes. I don’t see it as a question of effectiveness, but symbolic. Like Maluf has an arrest warrant in NY and is convicted in France. I see no issue of sovereignty. And there is a justification for doing this in Venezuela and not other places because the prosecutor general was dismissed and it’s a dictatorship

Deltan – 14:50:42 – The purpose of prioritizing would be to contribute to the struggle of a people against injustice, revealing facts and showing that if there is no accountability there it’s because there is repression. As to ending the possibility of a prosecution there, we can act on only some of the facts, which would solve the problem

“You Guys Who Wanted to Leak the Venezuela Stuff, Here’s Your Moment.”

After talking to Moro on the afternoon of August 5, 2017, Dallagnol went on to discuss the matter with his colleagues in the group “Filhos do Januario 2,” or “Children of Januario 2,” one of the prosecutors’ many chat groups. The conversation lasted several hours, going late into the night.

August 5, 2017 – Filhos do Januario 2 group

Paul – 19:23:59 – But folks, let’s reflect. I had already talked to Orlando about this. Realize that a civil war is possible there and any action by us could lead to more social upheaval and more deaths (even if the action is just or right). It’s not Brazi over there.

Paul – 19:24:33 – I’m not saying yes or no, just that it needs to be thought out

Roberson MPF – 19:26:38 – Daaaaamn

Orlando SP – 19:29:47 – Guys, about Venezuela. You can’t just open up what we have. We’d violate the agreement. We can’t risk a breach of agreement, including civil consequences for us, as well as for the nation.

Orlando SP – 19:30:44 – The solution of doing something here, I think would take a long time. We would have to put together an indictment or something similar, without hearing people, etc. I don’t think the timing would work.

Roberson MPF – 19:30:47 – I think that if we take action here we wouldn’t violate the agreements, Orlandinho

Orlando SP – 19:31:02 – But the problem is the timing

Orlando SP – 19:31:50 – The solution I see is to make a spontaneous communication to the country itself. Along the way this will surely leak somewhere, without our involvement. This I can do right away.

Orlando SP – 19:32:39 – Without the onus of working on an indictment

Orlando SP – 19:33:25 – As for the indictment, we would certainly face fierce criticism, but then Moro will decline to the capital and good …. the fact will be revealed.

A little over two hours later, Dallagnol replied to the group and pushed forward the argument for action, saying sarcastically, “Let’s do Maduro a favor,” but also pointing out possible impediments to their plan:

August 5, 2017 – Filhos do Januario 2 group

Deltan – 21:47:19 – PG, regarding risk, it’s something that is up to the Venezuelan citizens to ponder. They have the right to rebel.

[Unidentified Prosecutor] – 22:21:18 – In any case, it’s necessary to analyze the facts thoroughly, because if they’re under seal by the STF it won’t be possible to use them. Furthermore, Maduro has immunity and, except for human rights issues, it’s difficult to prosecute, at least while he’s in power. But we shouldn’t dismiss the idea entirely. Anyway, we’d still have to convince Russo.

Deltan – 22:35:57 – Russo says that we have to evaluate the viability. Meaning, he’d consider it

Deltan – 22:36:19 – He did not reject it prima facie, which I take as an opening to concretely analyze it with perspective

Deltan – 22:36:22 – good

On the afternoon of August 28, Car Wash prosecutor Orlando Martello sent a message to the group relating a telephone conversation he’d had with Vladimir Aras. At the time the secretary of international judicial cooperation for the public prosecutor, Aras had said in early 2016 that he did not trust Ortega. “We have good contacts with one or two prosecutors in Venezuela, but the PGR” — the prosecutor general — “there does not inspire confidence in us,” he said in one of the Car Wash prosecutors’ chat groups. But based on the tone of the call with Martello, apparently Aras had changed his mind, and Ortega became the crucial point of contact for clandestine cooperation with their Venezuelan counterparts.

According to the chats, Aras organized a reception for two Venezuelan prosecutors who secretly came to Brazil in mid-September to share notes on corruption in Venezuela. But the visit was Ortega’s idea. Two Car Wash prosecutors in Curitiba offered to host them in their homes, while Dallagnol privately asked the executive director of the anti-corruption advocacy group Transparency International to foot the bill for their trip in Brazil.

Ortega, in her self-imposed exile, came to Brazil ahead of her two colleagues. It had been two weeks since the Car Wash task force began to put their plan in motion. “You guys who wanted to leak the Venezuela stuff, here’s your moment. The woman is in Brazil,” wrote Car Wash task force member Galvão. His colleagues in the chat group reacted as if he was joking.

On October 12 and 14, less than a month after the prosecutors visited Brazil, Ortega published a pair of videos on her website. The releases appeared to be timed for maximum impact: A hotly disputed gubernatorial election in Venezuela would take place on October 15. (Ortega did not respond to The Intercept’s request for comment.)

The videos Ortega published were excerpts from the deposition of the former Odebrecht director in Venezuela, Euzenando Azevedo, in which he admits to having negotiated a secret $35 million payment to Maduro’s 2013 election campaign on behalf of the company, as well as giving millions more to state and local campaigns. In his deposition, Azevedo named several key Maduro allies. But the videos released by Ortega did not contain all the allegations Azevedo made during his deposition: He also admitted to giving $15 million to the campaign of Maduro’s 2013 rival, opposition candidate Henrique Capriles.

The leak incensed officials at Odebrecht. The company filed a complaint with the Supreme Court in which it strongly insinuated that the leak must have come from the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which oversaw the Car Wash investigation. “The video depositions of all of the company’s employees who are cooperating witnesses, especially those that deal with facts abroad, are under the custody of the PGR, and have never been officially handed over to cooperating witnesses, their lawyers, or anyone else,” the complaint reads. Last month, current Brazilian Prosecutor General Raquel Dodge revealed that there is an active investigation into the matter under seal in the Federal Court in Brasília.

When questioned for this story, the Brazilian Public Prosecutor’s Office said that, at the time of Ortega’s publication of the videos, Brazil and Venezuela had an information sharing agreement for another Car Wash-related deposition — but it did not include information about Odebrecht.

Risk to Life

Following the leak, Mauricio Bezerra, an Odebrecht lawyer, sent a message to Carlos Bruno Ferreira, of the International Cooperation Secretariat of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The message was passed on to the “Filhos do Januario 2” chat group by prosecutor Roberson Pozzobon. In it, Bezerra complains that the leak “significantly increased the risk” for several of the involved parties:

October 13, 2017 – Filhos do Januario 2 group

Roberson MPF – 15:36:44 –  Good evening. Unfortunately, as in August, we were once again surprised by the disclosure of a video of one of our cooperating witnesses’s depositions conducted by PGR during the final phase of the cooperation process. This time, unlike what has happened in the past, the audio became public through the ex-prosecutor of Venezuela, Ms. Luiza Ortega, exiled and in opposition to the current Government, as you can see in the link below. More serious still is that the video was disclosed at a time when we are conducting delicate negotiations with that country, as we informed you. The video’s disclosure significantly increased the risk to our members, Venezuelan citizens, and our operations. We are already taking precautionary measures. Tomorrow we will make a new request for the leak of these videos to be investigated. It is important that the PGR opens an investigation as soon as possible to ascertain the facts and ensure that events of this nature do not continue, since in addition to harming the upright investigation of the facts, they put at risk the physical integrity of our employees and their families. Thank you always for your attention, Mauricio Link: https://www.oantagonista.com/en/video-executivo-da-odebrecht-confirma-us-35-milhoes-para-maduro/

Good evening. Unfortunately, as in August, we were once again surprised by the disclosure of a video of one of our cooperating witnesses’s depositions conducted by PGR during the final phase of the cooperation process. This time, unlike what has happened in the past, the audio became public through the ex-prosecutor of Venezuela, Ms. Luiza Ortega, exiled and in opposition to the current Government, as you can see in the link below. More serious still is that the video was disclosed at a time when we are conducting delicate negotiations with that country, as we informed you. The video’s disclosure significantly increased the risk to our members, Venezuelan citizens, and our operations. We are already taking precautionary measures. Tomorrow we will make a new request for the leak of these videos to be investigated. It is important that the PGR opens an investigation as soon as possible to ascertain the facts and ensure that events of this nature do not continue, since in addition to harming the upright investigation of the facts, they put at risk the physical integrity of our employees and their families. Thank you always for your attention, Mauricio Link: https://www.oantagonista.com/en/video-executivo-da-odebrecht-confirma-us-35-milhoes-para-maduro/

Roberson MPF – 15:36:44 – Dear colleagues, good morning. The above message was sent by dr mauricio Bezerra to dr Carlos Bruno this morning. I’m sharing it with you.

Roberson MPF – 15:38:01 – Do you know if the audio had already been shared with them, PG?

Paulo – 15:48:22 – We did not pass it on … Only if it were Vlad

Paulo – 15:48:28 – Or Orlando, secretly

The physical risk to Odebrecht employees and others, mentioned by the company’s attorney, had been a concern previously raised by the task force itself. In December 2016, Dallagnol opposed the disclosure of similar information, recognizing that it was potentially explosive. “I am worried with the broadcast of the international information,” he wrote in the draft of a letter in English that he shared with his colleagues through a chat. The first justification he listed was “to avoid life risks for Odebrecht employees in countries such as Angola and Venezuela, since the contracts are still going on there.”

Recent revelations by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists found that Odebrecht paid at least $142 million in bribes for lucrative contracts in Venezuela, but had only revealed $98 million to prosecutors.

Odebrecht and a lawyer who represents former Odebrecht executive Euzenando Azevedo both declined to comment for this story.