Above Photo: Gary Cohn, Director of the National Economic Council, and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin are both former Goldman Sachs employees.

Google is blocking our site. Please use the social media sharing buttons (upper left) to share this on your social media and help us breakthrough.

A new report documents all the ways former Goldman Sachs employees are using their high-level government jobs to push an agenda that would boost the bank’s profits — at the expense of the rest of us.

Goldman Sachs has been a conspicuous presence at the scene of one disaster after another in the past half century. The bank is a leader in a Wall Street business model that relies on market manipulation and unsustainable financial bubbles to enrich a few insiders, but that produces disastrous consequences for the rest of us.

We are witnessing what may be a new Golden Age for Goldman Sachs. After running a campaign in which he lambasted the “corrupt” ties between Wall Street and Washington, President Trump has handed the job of shaping economic policy over to Wall Street insiders generally, and to alumni of Goldman Sachs in particular. These appointments add up to a level of inside influence that is unusual even by Goldman’s historic standards. And future picks could produce even more Goldman influence.

In choosing Gary Cohn as National Economic Council Director and Steve Mnuchin as Treasury Secretary, along with Jay Clayton at the Securities and Exchange Commission, Trump has turned to Wall Street veterans with deep knowledge of the financial crisis—knowledge gained as champions of the dangerous practices that helped cause it.

In areas ranging from financial regulations, to taxes, to infrastructure, to trade, this Goldman-heavy Administration is promoting policies that would boost Goldman Sachs’s profits, in many ways, at the expense of taxpayers and the broader public. Goldman’s stock price has already soared.

Meanwhile, Goldman’s drumbeat of scandal continues right on up to the present. Since 2010 alone, according to one recent study, Goldman Sachs has paid over $9 billion in fines and penalties associated with thirteen different patterns of fraud, abuse, or misconduct. Suspicion is also growing that Goldman may have been involved in manipulation of the U.S. Treasury markets—one of the world’s largest and most important financial markets, and a market with profound implications for American taxpayers. Since the Trump Administration is responsible for completing this investigation, the extensive Goldman Sachs influence in the Administration creates a major conflict of interest.

Drawing from a new report by Americans for Financial Reform, we highlight below what Goldman’s economic policy agenda could mean for us.

Cutting back Wall Street oversight and reducing consumer protections

As the major bank that is most dependent on revenues from aggressive trading practices, Goldman Sachs is in the forefront of efforts to roll back financial regulations that makes things fairer and safer for the rest of us, in order to preserve high profits from speculative and dangerous activity.

These include protections against fraud at the expense of investors and consumers, restrictions on bank risk-taking, and measures to separate ordinary commercial banking from Wall Street trading activities which were enacted under the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 in response to the financial crisis.

In developing these protections, Congress paid particular attention to the pre-crisis conduct of the big banks, citing some of the activities of Goldman Sachs as prime examples of the need for key reforms.

Since the Dodd-Frank Act was adopted, Goldman has continued to be profitable, but it has been forced to shed many of its riskiest investments and activities and to raise additional capital to support others, in order to come into compliance with new protections. In a naked push for higher profits, Goldman has staunchly opposed many of the new rules, falsely claiming they are a “burden” on financial markets and “damaging to the economy.”

Cutting business and investment taxes

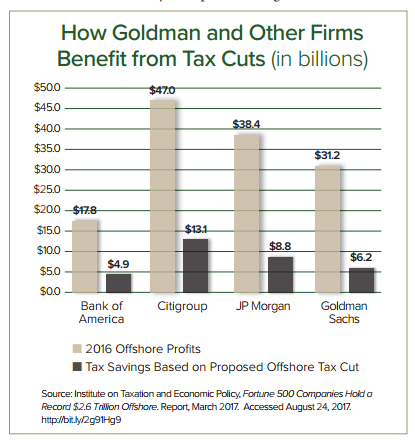

Goldman Sachs is already an expert tax dodger. The bank avoided $5.5 billion in taxes between 2008 and 2015. And under Trump’s tax plan it will be well positioned to avoid much more.

When it comes to U.S. earnings, cuts in the overall corporate tax rate disproportionately benefit major Wall Street banks. That’s because financial firms typically have fewer deductions for their on-shore earnings than do other companies such as manufacturing firms. Goldman’s effective U.S. income tax rate in 2016, for example, was in the range of 28%, which would translate to a massive tax cut of almost 10 percentage points based on the proposed new lower corporate rate of 20%.

The exemption for overseas earnings would generate windfall profits for Goldman and other large corporations, but the evidence of past cuts in taxes on offshore profits suggest that there would be no benefit for U.S. workers. Goldman currently has some $25 billion in foreign earnings technically held overseas to avoid U.S. taxes.

The exemption for overseas earnings would generate windfall profits for Goldman and other large corporations, but the evidence of past cuts in taxes on offshore profits suggest that there would be no benefit for U.S. workers. Goldman currently has some $25 billion in foreign earnings technically held overseas to avoid U.S. taxes.

By also significantly cutting tax rates on business entities structured as partnerships or pass-through entities, the plan would cut taxes on hedge fund managers and owners. Managing an investment fund is a frequent choice for Wall Street professionals when they decide to leave major firms, like Goldman. Steve Mnuchin built a considerable share of his post-Goldman fortune by managing an investment fund.

These tax changes are gold to Goldman and its executives, but threaten the rest of us by draining away revenue needed to pay for crucial public goods. Reform of the tax system to benefit the majority of Americans would include having Wall Street pay a larger share of taxes, not a shrinking share.

Privatizing government infrastructure

The Trump campaign promised to “Make America Great Again”—and a massive infrastructure package was a big part of that promise. But from what the Administration has said so far, its infrastructure plan would do more for the greatness of Goldman Sachs and other big Wall Street players than it would for ordinary Americans.

As presented thus far, the infrastructure plan would rest heavily on the idea of giving Wall Street investors tax credits in exchange for contracting with the government to finance, construct, maintain, and operate critical infrastructure. That amounts to a government-subsidized privatization of infrastructure through so-called “Public Private Partnerships,” known as P3s.

In addition to qualifying for Federal government tax credits by kicking in some of its own money, Wall Street would also get a stream of continuing benefits. For example, rather than build a road that everyone can ride for free, private investors could charge fees for its use. Alternatively, government could commit to paying regular “availability fees” as long as the infrastructure remains available for use.

Wall Street banks like Goldman, who assemble these deals, can make a tidy profit advising the government and helping them sell off infrastructure. The banks can also profit from their own investments in infrastructure. Goldman has already raised over $10 billion for a private infrastructure fund which it manages. And with deals that sometimes last for 75 years or more, the public can have the privilege of paying Wall Street to use public goods for generations.

Changing the rules of trade policy

Another promise of the Trump campaign was to change trade agreements in order to benefit American workers and bring jobs home. With Goldman in charge, that’s unlikely to happen. The firm has been a longtime champion of pro-corporate and pro-outsourcing trade policies.

Goldman has engaged in a decade-long effort to liberalize global trade rules as to make it easier for financial multinationals to invest without regard for national regulations that protect people and the environment. Goldman was a prominent member of the U.S. business coalition lobbying for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Faryar Shirzad, the head of Goldman’s Government Affairs Department, urged the inclusion of “investor state dispute settlement” (ISDS) provisions in trade agreements. Such provisions would allow businesses making cross-border investments to sue signatory governments for damages if rules or regulations interfered with expected corporate profits, and to have their lawsuits heard by special tribunals staffed with private attorneys who often have close ties to corporate interests. ISDS provisions can have a chilling effect on governments’ willingness to create laws to protect citizens and the environment, from fear that investors may sue for damages. Cohn and other Goldman Sachs alumni have already assumed a central role in making the Trump Administration more supportive of business-friendly trade agreements.

Taking on the predatory power of Government Sachs

Trump promised that Wall Street’s Washington power and influence would shrink, but they have in fact only increased. Perhaps more than any other Wall Street firm, Goldman Sachs embodies the combination of Wall Street excess and Washington power. And more than ever, we must take on Wall Street and build a financial system that works for ordinary people.