Above photo: From Chicago Community Bond Fund.

Prisons and jails are amplifiers of infectious diseases such as COVID-19, because the conditions that can keep diseases from spreading – such as social distancing – are nearly impossible to achieve in correctional facilities. So what should criminal justice agencies be doing to protect public health?

On this page, we’re tracking examples of state and local agencies taking meaningful steps to slow the spread of COVID-19. (So far, however, no state or municipality has implemented all of our five key policy ideas, nor met the demands issued by various organizations nationwide.)

Can’t find what you’re looking for here? See our list of other webpages aggregating information about the criminal justice system and COVID-19.

Releasing people from jails and prisons

We already know that jails and prisons house large numbers of people with chronic diseases and complex medical needs who are more vulnerable to COVID-19, and one of the best ways to protect these people is to reduce overcrowding in correctional facilities. Some jails are already making these changes:

- District attorneys in San Francisco, California and Boulder, Colorado have taken steps to release people held pretrial, with limited time left on their sentence, and charged with non-violent offenses. (March 11 and March 16)

- Ohio courts in Cuyahoga County and Hamilton County have begun to issue court orders and conduct special hearings to increase the number of people released from local jails. On a single day, judges released 38 people from the Cuyahoga County Jail, and they hope to release at least 200 more people charged with low-level, non-violent crimes. (March 14 and March 16)

- In Travis County, Texas, judges have begun to release more people from local jails on personal bonds (about 50% more often than usual), focusing on preventing people with health issues who are charged with non-violent offenses from going into the jail system. (March 16)

- Court orders in Spokane, Washington and in three counties in Alabama have authorized the release of people being held pretrial and some people serving sentences for “low-level” misdemeanor offenses. (March 17 and March 18)

- In Hillsborough County, Florida, over 160 people were released following authorization via administrative order for people accused of ordinance violations, misdemeanors, traffic offenses, and third degree felonies. (March 19)

- In Arizona, the Coconino County court system and jail have released around 50 people who were held in the county jail on non-violent charges. (March 20)

- More than 85 people (almost 7% of the jail’s population) have been released from the Greenville County Detention Center in Greenville, South Carolina, following a state order from the Supreme Court Chief Justice Donald Beatty urging South Carolina judicial circuits to avoid issuing bench warrants and start releasing people charged with non-violent offenses. (March 20)

- In Salt Lake County, Utah, the District Attorney reported that the county jail plans to release at least 90 people this week and to conduct another set of releases of up to 100 more people in the next week. (March 21)

- New Jersey Chief Justice Stuart Rabner signed an order calling for the temporary release of 1,000 people from jails(almost a tenth of the entire state’s county jail population) across the state of New Jersey who are serving county jail sentences for probation violations, municipal court convictions, “low-level indictable crimes,” and “disorderly persons offenses. (March 23)

- The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has reduced their jail population by 10% in the past month to mitigate the risk of virus transmission in crowded jails. To reduce the jail population by 1,700 people, the Sheriff reports releasing people with less than 30 days left on their sentences and the Department is considering releasing pregnant women and older adults at high risk. (March 24)

- New York City has released 200 people from Rikers Island in the past week, and expects to release another 175 people before the weekend. (March 26)

- In New Orleans, Louisiana, the District Court judges have issued orders calling for the immediate release of people held in the New Orleans jail awaiting trial for misdemeanors, arrested for failure to appear at probation status hearing, detained in contempt of court, or detained for failing a drug test while on bond. (March 26)

- The Legal Aid Society in NYC secured the immediate release of over 100 individuals held at Rikers Island on non-criminal, technical parole violations. (March 27)

- In New York, Governor Cuomo announced that up to 1,100 people who are being held in jails and prisons across the state will be released with community supervision. (March 27)

- In Allegheny County, PA, 545 people held in the county jail were approved for release by the courts and physically discharged from custody. (March 27)

Prisons have not been as quick to change policies and arrange for releases. But state prisons are filled with people with preexisting medical conditions that put them a heightened risk for complications from this virus. So far, we are aware of only a handful of state corrections departments taking steps to reduce the prison population in the face of the pandemic:

- The North Dakota parole board granted early release dates to 56 people (out of 60 people who applied for consideration) held in state prison with expected release dates later in March and early April. (March 21)

- The director of the Iowa Department of Corrections reported the planned, expedited release of about 700 incarcerated people who have been determined eligible for release by the Iowa Board of Parole. (March 23)

- In Illinois, the governor signed an executive order that eases the restrictions on early prison releases for “good behavior” by waiving the required 14-day notification to the State Attorney’s office. The executive order explicitly states that this is an effort to reduce the prison population, which is particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 outbreak. (March 23)

- The Director of the Rhode Island Department of Corrections is submitting weekly lists of people being held on low bail amounts to the public defender’s and attorney general’s offices for assessment in efforts to have them released. (Rhode Island is one of a handful of states that do not have jails, meaning that pretrial detainees are held in prisons.) The state DOC is also evaluating people with less than 4 years on their sentences to see if they can apply “good time” and release them early. (March 25)

- In an executive order, the governor of Colorado granted the director of the Department of Corrections broad authority to release people within 180 days of their parole eligibility date, and suspended limits on awarding earned time, to allow for earlier release dates. (March 26)

- The Utah Department of Corrections has recommended over 80 people for release from state prisons to the Board of Pardons and Parole. The DOC reports that the people referred for release are within 90 days of completing their sentences. (March 26)

- At least 6 women and their babies were released from a special wing that houses mothers and newborn babies at Decatur Correctional Center in Illinois. (March 27)

- The Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles has begun to review approximately 200 people for early release. They are considering people serving time for nonviolent offenses who are within 180 days of completing their prison sentences (or of their tentative parole date). (March 31)

- The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) announced on March 31 that it would expedite the transition to parole for nonviolent offenders with 60 days or less left on their sentences, with priority going to individuals with less than 30 days left. (March 31)

Reducing jail and prison admissions

Lowering jail admissions reduces “jail churn” — the rapid movement of people in and out of jails — and will allow the facility’s total population to drop very quickly.

- In Bexar County, Texas, Sheriff Javier Salazar released a COVID-19 mitigation plan that includes encouraging the use of cite and release and “filing non-violent offenses at large,” rather than locking more people up during this pandemic. (March 14)

- Baltimore, Maryland State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby will dismiss pending criminal charges against anyone arrested for drug offenses, trespassing, and minor traffic offenses, among other nonviolent offenses. (March 18)

- District attorneys in Brooklyn, New York and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, have taken steps to reduce jail admissions by releasing people charged with non-violent offenses and not actively prosecuting low-level, non-violent offenses. (March 17 and March 18)

- Police departments in Los Angeles County, California, Denver, Colorado, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania are reducing arrests by using cite and release practices, delaying arrests, and issuing summons. In Los Angeles County, the number of arrests has decreased from an average of 300 per day to about 60 per day. (March 16 and March 17)

- The state of Maine vacated all outstanding bench warrants (for over 12,000 people) for unpaid court fines and fees and for failure to appear for hearings in an effort to reduce jail admissions. (March 17)

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) notified Congress that they will halt arrests except for those deemed “mission critical” to “maintain public safety and national security.” In the statement, ICE also stated that they would avoid arrests near necessary healthcare services like hospitals, doctor’s offices, and clinics, “except in the most extraordinary of circumstances.” (March 18)

- In response to the Oklahoma Department of Corrections’ decision not to admit any new people to state prisons, Tulsa and Oklahoma counties are trying to keep their jail population down by not arresting people for misdemeanor offenses and warrants, and by releasing 130 people this past week through accelerated bond reviews and plea agreements. (March 22)

- In King County, Washington (Seattle), jails are no longer accepting people booked for misdemeanor charges that do not present a public safety concern or people who are arrested for violating terms of community supervision. The Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention is also delaying all misdemeanor “commitment sentences” (court orders requiring someone to report to a jail at a later date to serve their sentence). (March 24)

Reducing prison admissions reduces the risk of viral transmission into the prison population and helps maintain a prison population size to which the facility can provide appropriate medical care.

- The Oklahoma Department of Corrections announced that they are suspending admissions of newly sentenced individuals to state prisons, in an effort to prevent the virus from spreading rapidly behind prison bars. (March 22)

- California’s Governor Newsom signed an executive order halting new intakes at California’s five state prisons and the four juvenile facilities, stating that the effort is to prevent transmission of the virus from jails into state prisons. (March 24)

- The governor of Colorado issued an executive order that gives the Department of Corrections director the authority to refuse to admit people to state prisons. (March 26)

- In Illinois, an executive order from the governor has halted new admissions to state prison facilities. (March 26)

Reducing incarceration and unnecessary face-to-face contact for people on parole and probation

Limiting unnecessary check-ins and visits to offices for people on parole, probation, or on registries will reduce the risk of viral transmission. We don’t (yet) know of many recent reforms in this area, but there is an important letter from current and former probation and parole executives saying what must be done to promote social distancing and continuing to support people under supervision.

- The California Department of Adult Parole Operations has reduced the number of required check-ins to protect staff and the supervised population by suspending office visits for people 65 and older, and those with chronic medical conditions. (March 17)

- The Rhode Island Department of Corrections announced that probation and parole offices will not hold in-person check-ins and that individual parole or probation officers will provide instructions to people on parole and probation about maintaining appropriate remote communication. (March 18)

- The Arkansas Department of Corrections Division of Community Corrections has suspended supervision fees for the month of April 2020 and suspended face-to-face office visits. (March 20)

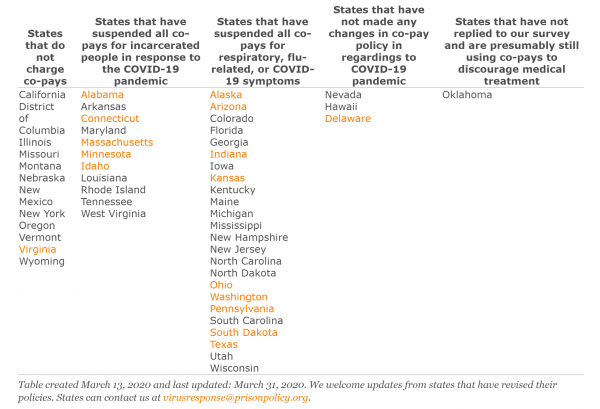

Eliminating medical co-pays

In most states, incarcerated people are expected to pay $2-$5 co-pays for physician visits, medications, and testing. Because incarcerated people typically earn 14 to 63 cents per hour, these charges are the equivalent of charging a free-world worker $200 or $500 for a medical visit. The result is to discourage medical treatment and to put public health at risk. In 2019, some states recognized the harm and eliminated these co-pays. We’re tracking how states are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic:

Reducing the cost of phone and video calls

Most federal prisons, state prisons and many local jails have decided to drastically reduce or completely eliminate friends and family visitation so as to reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure in facilities. In normal times, we would point to the significant evidence that sustained meaningful contact with family and friends benefits incarcerated people in the long run, including reducing recidivism. But it is even more important, in this time of crisis, for incarcerated people to know that their loved ones are safe and vice versa. While many facilities have suspended in-person visitation, only a few have made an effort to supplement this loss by waiving fees for phone calls and video communication. Here is one notable example:

- Shelby County, Tennessee suspended jail visitations, but to maintain these vital connections between families, they are waiving fees for all phone calls and video communication. (March 12)

Other jurisdictions have implemented cost reductions that – while better than nothing – still severely restrict contact between incarcerated people and their loved ones:

- The Utah Department of Corrections is giving people in prison 10 free phone calls per week, with each call limited to 15 minutes. (Calls that go beyond the 15-minute limit will incur charges.)

- Prisons in Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Vermont, and Pennsylvania are offering residents even smaller numbers of free calls per week. The same is true for jails in Middlesex County, Massachusetts; Harris County, Texas; and Montgomery County, Ohio.

Other resources

With thousands of jurisdictions making ongoing policy changes, and local advocacy groups across the country issuing new demands, it’s impossible to track all ongoing developments in one place. If you didn’t find what you were looking for here, try these other pages:

- On March 23, the CDC released guidelines for correctional and detention facilities to protect the health and safety of incarcerated people, staff, visitors, and the community at large.

- The Justice Collaborative COVID-19 Response and Resource page offers resource lists, fact sheets, example demand letters, and tracks active demand campaigns throughout the U.S.

- Professor Sharon Dolovich at the UCLA School of Law has shared a growing comprehensive spreadsheet including results from a state-by-state survey of changes in visitor policies, requests for population reduction, and actions taken to reduce the incarcerated population.

- The Justice Management Institute has catalogued updates on criminal justice system responses to COVID-19 at the state and local levels, including changes being made by jails systems, law enforcement agencies, probation and parole systems, prosecutors, and public defenders.

- The Appeal is tracking demands and local and state government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. This information is organized both geographically and chronologically and includes policies regarding the justice system, elections, healthcare and insurance, and paid sick leave.

- Professor Aaron Littman at the UCLA School of Law has compiled a spreadsheet to help readers understand which local officials have the power to release people from jails. The information in the spreadsheet is state-specific.

- The Marshall Project is tracking articles from across the web on the risks of coronavirus across the U.S. justice system.

- COVID-19 Behind Bars is an independent journalism project tracking cases of coronavirus in jails, prisons, detention centers, and other correctional facilities in the U.S. and internationally using news reports and potential cases reported on by people inside prison.

- Professor Margo Schlanger at the University of Michigan Law School is tracking all COVID-19 class-action and group litigation (jails, prisons, immigration detention) cases at the Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse.

Help us update this page

If you know of notable reforms that should be listed here, please let us know at virusresponse@prisonpolicy.org.