Above photo: Coal power was declining before the onset of AI and Trump came into power. Sari Williams.

Utilities started reversing coal power’s “irreversible” decline.

Will it last?

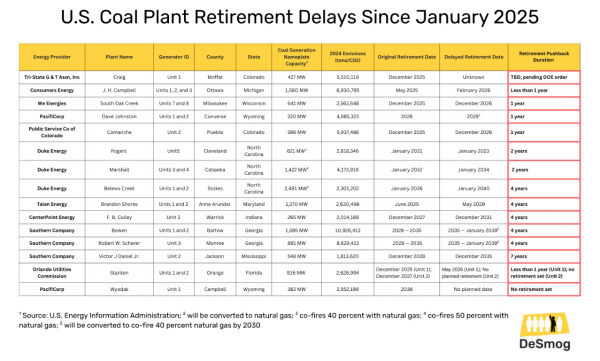

Since the second Trump administration took power in January, at least 15 coal plants have had planned retirements pushed back or delayed indefinitely, a DeSmog analysis found.

That’s mostly due to an expected rise in electricity demand, a surge largely driven by the rise of high-powered data centers needed to train and run artificial intelligence (AI) models. But some of the plants have been ordered to stay open by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), despite significant environmental and financial costs. Energy Secretary Chris Wright, a former fracking executive, has frequently cited “winning the AI race” as a rationale for re-investing in coal.

The fossil fuel facilities are located in regions across the country, from Maryland to Michigan and Georgia to Wyoming. Together, their two dozen coal-fired generators emitted more than 68 million tons of carbon dioxide in 2024. That’s more than the total emissions of Delaware, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. combined.

Nearly 75 percent of the coal plants were on track to shutter in the next two years.

The delays buck the overall trend in the U.S., where coal’s importance as an energy source has diminished rapidly over the past two decades. Coal’s critics say this broad-based phaseout is an urgent matter of public and environmental health. Often called the “dirtiest fossil fuel,” coal creates more climate emissions per gigawatt-hour of electricity than any other power source. And the human impacts of its pollution have been profound: A 2023 study in Science attributed 460,000 extra U.S. deaths between 1999 and 2020 to sulfur dioxide particulate pollution belched out by coal plants.

Cara Fogler, managing senior analyst for the Sierra Club, called the recent spate of delayed closures “unacceptable.”

“We know these coal plants are dirty, they’re uneconomic, they’re costing customers so much money, and they’re polluting the air,” said Fogler, who co-authored a report showing many utilities have backtracked on climate commitments, including coal phaseouts, often citing data centers as a cause. “They need to be planned for retirement, and it’s really concerning to see utilities becoming so much more hesitant to take those steps.”

DeSmog identified the 15 plants by examining changes to the planned retirement dates listed by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), a DOE agency that compiles data on energy providers, as well as public statements from utilities and the Trump administration. Some of the voluntary delays appear to directly contradict previous net-zero pledges made by several companies.

Neither the Department of Energy nor American Power, a trade association representing the U.S. coal fleet, responded to requests for comment.

What Led To Coal’s Decline?

Not long ago, coal really did keep the lights on. In 2005, it provided roughly half of America’s electricity, making it by far the dominant power source nationwide. But in the past two decades, coal’s market share has rapidly waned. No new coal plants have come online since 2013. These days, its footprint has dwindled, with just 16 percent of the overall energy mix.

In March 2017, President Trump appeared to blame environmental regulations for coal’s poor fortunes — a trend he promised to reverse.

“The miners told me about the attacks on their jobs and their livelihoods,” Trump said at U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) headquarters. “I made them this promise … My administration is putting an end to the war on coal.”

America is blessed with extraordinary energy abundance, including more than 250 years worth of beautiful clean coal. We have ended the war on coal, and will continue to work to promote American energy dominance!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 18, 2018

But environmental regulations didn’t kill coal. Instead, its demise became inevitable mostly thanks to the rise of a competing fossil fuel: natural gas.

Gas has both economic and technological advantages over coal, said David Lindequist, an economist at Miami University who co-authored a recent paper on the environmental impacts of the shale gas boom.

As new fracking technologies helped to flood the U.S. market with cheap gas in the mid-2000s, utilities began a broad coal-to-gas pivot that’s still underway today. Abundant, often less expensive gas flowed into power plants that operate more efficiently and nimbly than coal plants. This combination of price, efficiency, and flexibility made ditching coal an easy calculation for many utilities.

“The fact that we were able to so successfully phase out coal in the U.S. would never have happened without the fracking boom,” Lindequist said.

Today, coal is at an even greater disadvantage, as renewable energies continue to make economic and technological inroads. The International Renewable Energy Agency found that, in 2024, solar and wind routinely delivered electricity more cheaply than fossil sources of energy. That dynamic has helped solar in particular become the fastest-growing source of power in the U.S.

Meanwhile, America’s newest coal plant — the Sandy Creek plant near Waco, Texas, built way back in 2013 — is currently sitting idle after another catastrophic failure. It isn’t set to resume operations until 2027. The average U.S. coal plant is more than 40 years old, a factor that’s contributed to their decreasing reliability.

“These [coal] plants are so old that at this point there’s very little that could really revive the fleet,” said Michelle Solomon, manager in the electricity program at the nonpartisan think tank Energy Innovation. “I’ve been using the analogy of an old car: Nothing is going to bring my car that has 200,000 miles on it back to being a brand new, efficient car.”

During the Biden years, as technological advancements and historic subsidies made renewables even more attractive, observers broadly believed that coal’s days were numbered. The “writing was on the wall” for coal, Lindequist said.

“Coal may retain a grip in U.S. politics, but its actual role in the generation system is shrinking annually,” researchers for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis wrote in a 2024 report. “It is a trend we believe is irreversible.”

Yet even before Biden left office, a new dynamic began emerging: As tech companies started proposing billions in data center build-outs to feed the AI frenzy, utilities started to take a fresh look at their coal plants.

Data Centers Changed Coal’s Trajectory

In 2020, Dominion Energy, a utility that provides electricity to millions of customers across Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, announced non-binding plans to retire the Clover Power Station by 2025. Running the plant — an 877 megawatt (MW) coal-fired facility near Randolph, Virginia — would be uneconomical under any future scenario, the company found. It just didn’t make financial sense to keep it going.

It reversed course just three years later. Under its 2023 plan, Dominion projected that its energy demand from data centers would nearly quadruple by 2038. That’s an astonishing rise, considering that Virginia already leads the U.S. in data center development by a wide margin. Known as Data Center Alley, the state is home to more than one-third of the world’s largest-scale data centers. Today, Dominion says it doesn’t anticipate retiring any of its existing coal plants — including Clover — until at least 2045, the year that Virginia law stipulates its economy must be carbon-free.

Dominion wasn’t the only utility to cite data center growth as it backtracked on coal. In an August 2024 earnings call, executives of the Wisconsin-based utility Alliant Energy said that the company was “proactively working to attract” data center projects. A few months later, Alliant announced it would delay retiring the Columbia Energy Center, a coal-fired plant near Madison, from 2026 to 2029. The plant’s retirement had already been pushed back once.

The trend became notable enough to attract the attention of analysts at Frontier Group, an environmental think tank. In January 2025, Frontier analyst Quentin Good published a white paper showing that utilities had already cited data center growth as a rationale for delaying the phaseout of seven fossil fuel power plants across the U.S.

“We were concerned about the potential for all of this new electricity demand from data centers to slow down the transition to clean energy,” he told DeSmog. “In that report, we discovered it was basically happening already.”

But two other dynamics also began playing out in January: AI hype started to reach new levels of intensity, and power changed hands in Washington.

AI Hype Highs, New Coal Lows

Data centers aren’t the only reason for the recent upswing in electricity demand. Building electrification, industrial growth, and increased electric vehicle ownership all play roles, too. But nothing has quite caught utilities’ attention like data center projects, which are cropping up with highly localized impacts across the U.S. at a historic rate. Filled with stacks of high-powered computing equipment, the facilities are projected to account for about half of new electricity growth between 2025 and 2030.

On January 21, 2025 — one day after President Trump’s second inauguration — he revealed a new AI infrastructure joint venture involving ChatGPT parent company OpenAI called the Stargate Project, which would spend up to $500 billion on data center build-outs in the next four years. Tech executives announced the initiative’s details alongside Trump during the unveiling at a White House event.

Days later, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg said he planned to spend $65 billion on data center build-outs in 2025 alone, including one project “so large it would cover a significant portion of Manhattan.” These announcements followed a similar one from Microsoft in January: a pledge to spend $80 billion on data centers this calendar year.

As the world’s largest tech companies raced to outdo each other, a wave of delayed coal plant retirements followed.

On January 31, Southern Company, a utility serving over 9 million customers across 15 states, announced plans to delay the retirement of generators at two of the largest coal plants in the U.S., both in Georgia. The massive, coal-fired units — two at the Bowen Steam Plant outside Euharlee, and one at the Robert W. Scherer Power Plant in Juliette — had been scheduled to go offline between 2028 and 2035. Under its revised plan, the company pushed retirement back to as late as January 1, 2039(though both plants would be 40 percent co-fired with natural gas by 2030 in that scenario).

In legal documents and public statements, company spokespeople point to data centers as a key rationale for the delays. Last month, at an industry conference in Las Vegas, Southern Company CEO Chris Womack cited data center growth as a key factor keeping fossil energy online, according to the trade publication Data Center Dynamics.

“We’re going to extend coal plants as long as we can because we need those resources on the grid,” he reportedly said.

Next door in Mississippi, Southern Company also delayed the closure of a 500 MW generator at the Victor J. Daniel coal plant in Jackson County. It pushed the retirement back from 2028 until “the mid 2030s.” In documents filed with Mississippi’s Public Service Commission, the state’s utility regulator, Southern appeared to cite a 500 MW Compass Datacenters project as a reason for the change. Southern has pledged to be net-zero by 2050.

As the months passed, the same dynamic unfolded in other states. Alarmed, Good, the Frontier Group analyst, started to track the delays. By October, he published an update to Frontier’s report that found data centers had pushed back at least 12 coal plant closures in the past few years.

“The data center boom has shown no signs of abating,” he wrote. “Even more fossil fuel plants that had been scheduled to retire have been given a new lease on life.”

In its own analysis, DeSmog found that at least 15 coal plant retirements have been delayed since January 2025 alone. Together, those plants emitted nearly 1.5 percent of America’s total energy-related carbon dioxide emissions from 2024.

This comes at a time when the world’s nations need to cut their climate emissions roughly in half to avoid the worst impacts of global heating, according to a recent United Nations report.

But not all the delays can be attributed directly to data center growth. Some have stayed open for a different reason: top-down orders from the Trump administration.

The Department Of Energy Steps In

The J.H. Campbell Generating Plant, a 1.5 gigawatt coal plant in Ottawa County, Michigan, was scheduled to close May 31. The plant even held public tours to give a rare, behind-the-scenes look at aging fossil infrastructure, before it shut its doors for good.

“Now we know cleaner, renewable ways to generate electricity,” a Campbell employee told members of the public on a September 2024 tour.

But just eight days before scheduled to shutter, Department of Energy Secretary Chris Wright ordered Campbell to stay open another 90 days, citing an “emergency” shortage of energy in the Midwest.

Keeping the plant open cost its owner, Consumers Energy, almost $30 million in just five weeks, the company said. Though the plant’s closure was projected to save ratepayers more than $650 million by 2050, Campbell was costing more than $615,000 a day as of September. Yet Wright has since extended his order twice. Campbell now is scheduled to stay open until at least February 2026.

“The costs to operate the Campbell plant will be shared by customers across the Midwest electric grid region,” including customers serviced by other utilities, Matt Johnson, a Consumers Energy spokesperson told DeSmog by email.

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel is challenging DOE’s order to keep Campbell open, calling the orders “arbitrary.”

“DOE is using outdated information to fabricate an emergency, despite the fact that the truth is publicly available for everyone to see,” Nessel said in a November 20 press release. “DOE must end its unlawful tactics to keep this coal plant running when it has already cost millions upon millions of dollars.”

Meanwhile, DOE is telling a very different story.

“Beautiful, clean coal will be essential to powering America’s reindustrialization and winning the AI race,” Wright said in September, as the Department of Energy announced $350 million in funding for coal plant upgrades, along with other incentives.

Energy Innovation’s Solomon called the funding “a waste of taxpayer dollars.”

“We’ve been calling it a ‘cash for clunkers’ program where you don’t trade in the clunker,” she said. “Trying to build a modern electricity system using the most expensive and least reliable source of power is really not the answer.”

However, the Trump administration said in September that it plans to feed the AI boom — with an estimated 100 gigawatts of capacity in the next five years — by keeping more old coal plants open. “I would say the majority of that coal capacity will stay online,” Wright said.

Executives from Colorado’s Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association confirmed to DeSmog that they also expect an order to keep a 421 MW coal-fired generator at Craig Station open past its December 2025 decommissioning date.

In late October, Colorado Congressman Jeff Hurd sent a letter to the Trump administration, urging it to extend the life of a 400 MW coal generator at the Comanche Power Station near Pueblo as the owner, Xcel Energy, works to repair the plant’s chronically troubled main reactor. The smaller unit was slated to go offline in December — but, in its case, the administration never needed to act. Last month, Xcel, with the help of Colorado Governor Jared Polis, began to lobby to keep it open at least another 12 months. The state utility regulator appears to have granted that request, according to an agreement with Xcel and other stakeholders.

This delay wasn’t just due to data centers, though their numbers are growing in Colorado. Xcel spokesperson Michelle Aguayo said the delay was “due to a convergence of issues,” including rising electricity demand, “supply chain challenges,” and the continued outage at the main generator. “We continue to make significant progress towards our emission reduction goals approved by the state which would require us to retire our coal units by 2030,” she said.

Delaying The Inevitable

Whether the data center boom will play out as projected is still a matter of speculation.

Last month, power consulting firm Grid Strategies reported that utilities may be overestimating electricity demand from data centers by as much as 40 percent. That’s due in part to the many hypothetical projects, and a widespread practice of double- and triple-counting. Tech companies tend to pitch utilities in multiple regions as they shop around for incentives, creating the appearance of demand from many more data hubs than actually will be built.

Experts have a name for this growing phenomenon: “phantom data centers.”

At the same time, a growing chorus of critics are warning of an AI bubble, arguing that runaway costs can’t justify the kinds of investment being floated. Even the head of Google’s parent company has acknowledged the “irrationality” of the boom.

Critics also says contradictory actions taken by the Trump administration — citing an “energy emergency” while canceling billions in funding for renewable projects — are making the problem worse.

Yet even with all the unknowns, one thing’s certain: Coal’s role in America’s power push can be extended, but it can’t last forever.

Seth Feaster, an IEEFA analyst, says even AI hasn’t changed the big picture: Eventually, coal will die, and it will be killed by other, cheaper forms of energy.

He called the current phenomenon a “period of pause and delay.” In his view, the technological and economic rationales for quitting coal remain undeniable.

“The policy changes here may have a delaying effect on the decline of coal, but they are certainly not changing the direction of coal’s future,” he told DeSmog.

The questions for now are, how long the delays will continue — and at what cost.