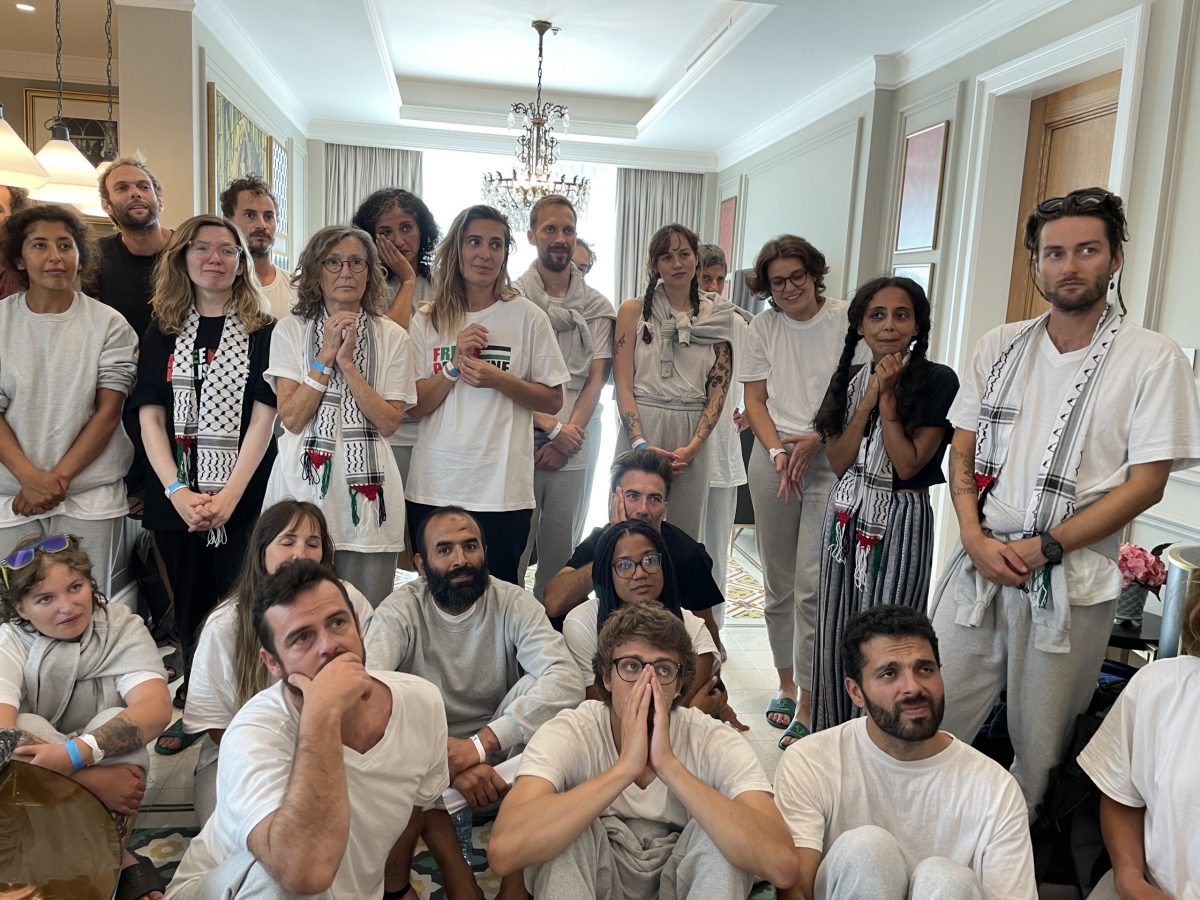

Above photo: Some of the 44 participants on the Conscience who were sent to Jordan after time in Israeli prison. Ann Wright.

The Gaza Freedom Flotilla Shipmates on the Ship “Conscience”.

This is the second article written by Ed DiGilio, a participant and crew member on the Gaza Freedom Flotilla ship Conscience.

The title of the article “Welcome to Hell” is the title of a report “Welcome to Hell: The Israeli Prison System as a Network of Torture Camps” on the horrific conditions for Palestinians in Israeli prisons written by the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem.

Ed’s first article on the Israeli attack on the Conscience, hours on the ship with IOF soldiers and processing on the docks of Ashdod harbor can be read here.

All Roads Lead to Ketziot

They loaded the bus with us and we sat there for a while without moving. “Don’t take your blindfold off, they have a camera,” someone observed.

“They are recording everything we are saying,” said another comrade.

I recognized the voice of the activist sitting next to me. He was a big guy, well over six feet tall. I was squashed into the corner of the last row of the bus. I tried to sit sideways to get more room. The steel seats of the bus made that difficult. It was uncomfortable. At least they didn’t zip tie my hands too tightly.

It must have been well after midnight when the bus started moving. We were all tired. I dozed fitfully, the whine of the bus transmission in my ears. At one point, I woke up in a panic. I had removed my blindfold while half asleep. The camera! I desperately tried to refit the blindfold over my eyes with clumsy zip-tied hands. It worked. No guards appeared. I guess no one was monitoring the camera very closely. Perhaps the guards were asleep as well?

How to sleep in such conditions? It’s simply a question of exhaustion. My head pitched forward, chin to my chest, I was going to get some rest. Just at that point, the bus hit a huge pothole and my face slammed down into the back of the seat in front of me. Ouch! I had bit my lip quite badly. I tasted blood. The inside of my lip was shredded. I was thankful I didn’t break any teeth. There would be no more sleep on this ride.

After driving for hours, the bus stopped. The guards came and ushered us off. The blindfolds were removed and the zip ties were cut off. We had arrived. The notorious Ketziot prison. They herded us all into a holding cell. It was packed with us. The prison lights were bright. A couple of my fellow activists looked brutalized. Four guards came into the cell and grabbed one of our comrades. It happened quickly. They dragged him out quite harshly and disappeared into the prison. I have no idea where they took him. We were getting nervous.

We went through the prison intake process. We were strip-searched and given proper prison clothing – gray sweats, a white t-shirt and sandals. We saw medical personnel and were photographed. “Do you need any medication?” we were asked.

“Yes, as a matter of fact, 1000 mcg. of B12 daily. I brought my medication with me,” I replied. Maybe they were going to take care of us after all?

At some point, I can’t recall when exactly, we were divided into small groups and brought to our cellblock. There was a box of jelly sandwiches in the hallway on the way to our cellblock. “If you are hungry, you can take a sandwich,” explained a guard.

Sheepishly, I took one. Some of my comrades were on hunger strike. No food, no water from the Israelis. I tried to be discreet. I hid the sandwich in my sweats. It was still dark. Maybe no one would notice? I felt a little guilty about it, but I’m old. I have health issues. I wasn’t up for protesting in the prison itself. What’s the use? In my view, it’s better to get outside as quickly as possible and start working again for the cause. So many excuses…

But many of my comrades were strict. Nothing from the Israelis. Certainly, a valid point.

I ate my jelly sandwich under cover of darkness in our cell.

Our cell. We were finally led to our cell. It stank of urine and consisted of four bunk beds in a room and a separate bathroom with a filthy toilet. There was a sink with a working faucet, which was our source of water for washing and drinking. There was a camera on the back wall mounted high up, close to the ceiling. We were being observed. We received towels, a small toothbrush and toothpaste and three small packets of liquid soap, which proved impossible for me to open. The bunks were noisy because they were supported by a steel sheet that flexed when one rolled over in bed. Boom! It sounded like a poorly constructed gong or something. I quickly learned to lie still.

We slept for a couple of hours. When morning came, there were a couple of guys from another flotilla at our door. They were delivering breakfast. I took more food. I think it was a roll with cream cheese and tomato. Some of my cellmates ate as well. Now that it was light, we could see some of the other cells on our block. The Israelis were housing us all together. The cellblock was filled with activists from our flotilla and one prior. We could talk between the cells. The acoustics of the cellblock were perfect for singing, with a big natural reverberating sound. I heard a song coming from a few cells down. It was sung to the tune of the Italian protest song Bella Ciao.

We need a toilet. A working toilet. We need a working toilet now, now, now.

We need a toilet. A working toilet. We need a working toilet now.

This verse repeated over and over for at least 15 minutes. It was coming from a cell full of our comrades from a previous flotilla. They had been in Ketziot for eight days. The Israelis were housing them in a cell without a working toilet, one that was overflowing with human waste. Ketziot could get nasty.

Adalah lawyers and the Israeli judge

The guards came for us in the morning. We were led out of the cellblock back to the holding cell. Many of our fellow activists were with us as well. They loaded us onto the bus and we drove for a few minutes. There were no windows on the bus but there were a couple of tiny cutouts in the walls towards the ceiling of the vehicle through which we could see the outside world. Someone spotted a fellow activist outside. We shouted her name through the walls. We were in custody, but we could still be noisy. The guards didn’t seem to mind.

The bus stopped. We were taken off in small groups of three and four and taken to a trailer office. The tribunal. We were being judged.

Our lawyer from Adalah was inside the office, along with a judge and an interpreter. We sat down. The lawyer explained that she had already made the legal arguments against our detention but we could add anything we wished. I chose to discuss the details of my torture. Others chose to complain that their electronics had been stolen and thrown away during the bag search. One of us mentioned that the water in our cell was undrinkable. We had tasted it the night before and it was reportedly disgusting.

“You need to run the tap for a few minutes before you drink,” offered our lawyer. “The water doesn’t taste too good, but it won’t make you sick.”

We were skeptical. The water in our cell was gross. Our cell was gross. They were keeping eight of our fellow activists in a cell without a working toilet.

It was clear nothing would be done about the water. We filed out of the tribunal. The judge had been typing the entire time we were with her but I had no idea about the outcome of our “trial.” The judge had said almost nothing to us. We got back on the bus, were driven to our cell block and returned to our cell. Except our cellmate from New Zealand was no longer with us. He hadn’t returned to the cell. It was worrying.

They lost our cellmate and the miracle of the water

We turned on the faucet in the bathroom. We hadn’t had a drop of water since we left the ship. One of us had smuggled an empty plastic bottle into our cell for use as a cup to drink from. Other than that, we had to drink from our hands. We let the water run for at least ten minutes. I drank from the spigot with my bare hands. The water was good! As good as any well water I’ve had in the U.S. Alhamdullilah! Praise be to the God of Abraham!

I drank a few handfuls. I was still getting over a head cold and didn’t want to share a plastic bottle with the others.

A guard appeared and counted the members of our cell. Where was New Zealand, he asked? “We don’t know. He never came back from the tribunal,” we replied.

The guard looked confused and walked away.

There was little to do in our cell. No books, paper or pencils were allowed. We lay down to rest. Some of us slept. One of us worried about his health. He had high blood pressure and hadn’t received his medication yet. I hadn’t received my medication either and no one seemed in a hurry to bring it.

We tried to discern the time of day by the position of the sun in the sky. Some of us in the cell had accepted Islam. We had constructed a mosque and were intent on saying our prayers. Four or five of us prayed the mid-day prayer together. It was a beautiful thing.

A guard appeared again, a different one. Where is New Zealand, he asked? “He’s not here. We already explained this to the other guard,” we replied.

The guard walked away looking confused.

U.S. Consular Affairs Officer Visited U.S. Citizens

They came and took us out of the cell by nationality and took us to the holding cell. We were being brought to see the U.S. consul. The consulate had traveled to the prison to meet us. It was a good sign. Previous flotillas with more U.S. citizens had never even received a visit from the consulate while in prison. I was happy to see the consul. I shook his hand warmly.

There were eight of us in the meeting. We all told our stories and signed forms that allowed the consulate to provide details of our condition to our families. The consul mentioned there was a possibility we could leave tomorrow on a plane chartered by the Turkish government. I refused to believe it. It didn’t seem possible.

The warden came over to tell us to wrap up our visit with the consul. “Two minutes,” he said.

We finished our business. The consulate left our holding cell. He shook hands and chatted with the warden. The warden was all smiles.

We were led back to our cell. A man appeared at the cell door and he had brought a meal for us. It was tuna salad. I’m a vegetarian and don’t eat tuna, but I ate around the fish and the food was pretty good. A pleasant surprise. They gave us enough so everyone in the cell could eat if they wanted to. We all went back to sleep. There wasn’t much to do in this prison.

I heard the guards come onto the cellblock and I went to the window at the cell door. There was a guard in riot gear holding a shotgun in front of our cell. There was another guard with a giant plexiglass shield standing in front of the cell directly to our right. I had no idea what they were doing. “Stand back!” said the guard with the shotgun.

I didn’t move. I was curious about what they were up to. The guard aimed the shotgun at me through the cell door window and illuminated my chest with the laser sight. I moved back a few feet. I was fairly confident I wasn’t going to get shot through the door of a locked cell in a prison in the Israeli desert. I wanted to see what the guards were doing. They went into the cell directly next to us. I was witnessing their protocol for entering the cells. One of my cellmates went directly to the window of our door. He was desperate for a cigarette. The guard with the shotgun illuminated his chest with the laser sight. “Can I get a cigarette please,” pleaded my cellmate.

The guard said nothing. In the cell, we burst into laughter. The theater of the absurd.

Towards the evening, another guard came by our cell looking for New Zealand. “He’s not here. How many times do we have to tell you?” we said.

The guard left in a huff. They had lost New Zealand. Had he escaped?

About half an hour later, a guard returned escorting New Zealand. We celebrated. They had accidentally put him in the wrong cell after he returned from the tribunal. A simple mix-up. Shortly after that, another guard came onto the block. He installed padlocks on the doors of every occupied cell. It seemed a bit redundant. The thought of sneaking out had never even occurred to me.

They came for us again in the evening and took us to be processed. They took pictures of us, front and back. I guess to prove that we were not harmed during our detention. As we were brought back to our cell, there was a guard posting signs in Hebrew on the doors of all the occupied cells on our block. “What’s it say?” we asked him.

“Go home,” the guard replied.

I refused to believe it. I thought they were just messing with our heads.

I slept terribly that night. I could hear the barking of the prison dogs in the distance. Maybe they were terrorizing Palestinian prisoners or something? Our block was quiet. When we heard the birds chirping outside, we prayed the dawn prayer together. It was a beautiful thing.

Leaving the Prison for a Flight to Istanbul

The guards came to get us at first light and loaded us on the prison bus. We were packed into the back of the bus, probably 20 guys in a locked compartment. There was a ventilation system on the bus but it struggled to keep us cool. Armed guards with automatic weapons sat outside. They loaded more of our comrades into the front of the bus and we set off. We drove for at least 20 minutes, then stopped. Someone looked through the tiny opening in the wall of the bus. “We’re at the gates of the prison. You can see the barracks where the guards live.” he reported.

I looked through the opening in the wall as well. I could see a vast row of buildings stretching out forever into the desert. Ketziot was huge. The bus moved on and we left the prison. Where were we going? To Tel Aviv? Jordan? The South? We had no idea and no one was telling us anything. We drove for hours through the desert. We observed one of the guards on the bus fall asleep. She was young, maybe in her early twenties with blonde hair and long fingernails painted red. She was wearing sunglasses. I thought the nails looked a little out of place with her fingers wrapped around her automatic rifle. Not the stereotypical prison guard.

Then an airport. We were in the South, near the Red Sea. The bus came to a stop. It didn’t seem possible. We sat on the bus for at least another 30 minutes. Even with the ventilation going, the cramped quarters were getting uncomfortable. The guards finally came to get us off. I was the second to last to leave. Just one activist behind me. Hardly anyone was around. I figured it was safe for some Shaloms. “Shalom,” I said to the prison guard as I walked off the bus. No reply.

The 100-meter walk to the terminal building was lined with prison guards. “Shalom,” I said to another guard. No reply again.

I arrived at the entrance to the terminal. The guard with the red fingernails was there. “Shalom,” I said.

“Shalom,” she replied as I walked into the building.

I kept walking and didn’t look back.

At the Airport in Israel and Flying to Istanbul

I walked through the airport terminal. I could hear my comrades shouting “Free Palestine!” in the concourse ahead of me. The Israelis in the terminal were hurling unprintable insults back at us in return. We made our way to the tarmac.

The Turkish government had sent a Turkish Airlines 737 to pick us up. I went up the stairs and boarded the plane. I was jubilant as I greeted the crew and my comrades on board. The plane was only a little more than half full, we still had 60 flotilla people in prison in the Negev. Regardless, we were thrilled to be leaving. It felt real. We had survived. All the tension of the previous two weeks melted away. The stress of the unknown was gone.

They hadn’t bombed the ship. They hadn’t shot us to pieces when they boarded us. They hadn’t kept us in detention for months. No one onboard the plane seemed physically wounded. These were things to celebrate.

We cheered the Turkish government for sending the plane. “Turkiye! Turkiye! Turkiye!” was our cry.

We flew out from Israel to Istanbul. The pilot came on the PA system. He said he was honored to have us all onboard.

I was exhausted.

Postscript

For my dear brother, a Palestinian refugee in Europe

My editor sent me a note today. He asked me how many more installments I planned to write. He said he appreciated the content, but was curious when I would be writing about my reflections on the Palestinians and what they are enduring because these reports have largely been about my, and my comrades’, experience with the Israeli state security apparatus. And my editor said he understood that, kind of.

So, I want to apologize to anyone who may be offended that I might have unintentionally used the suffering of the Palestinians to promote myself, or my agenda. That’s one of the dangers of these missions – Westerners such as myself use the attention the flotillas create to talk about things wholly unrelated to the question of Palestine.

I remember I was sitting in Malta back in the spring a few days before the Conscience was bombed. I was talking to a Freedom Flotilla captain. He said, “You know, as a middle-age white man, the best thing you can do here is to keep your mouth shut.”

I think that is sage advice. But here I am, yammering on for days, writing these reports because a friend asked me to provide an account of my experience for a small group of lovely activists I’m associated with. It has just turned into something I didn’t anticipate. So, please forgive me. I know I’m a flawed advocate for the Palestinian people.

And the Palestinian people don’t need me as an advocate. They have their voice and can articulate their desires and wishes for their future if we Westerners would just get out of the way and shut our mouths. But it’s hard for that to happen when Western governments such as mine sit squarely on the necks of the Palestinians. It seems we’re all bound together in the question of Palestine.

Can I offer any new insights on the situation? Probably not. My dear brother, who is a Palestinian refugee in Europe, believes the Palestinian people need justice as part of the process. I think that’s a good point. There’s no way to have a durable, lasting peace without justice. An acknowledgement that justice means something in Palestine would at least be a start.

Nonetheless, these matters are off in the future somewhere. God willing, in the not too-distant future. For now, the Freedom Flotilla sails to stop the genocide.

Memorial Service on the Conscience for those Killed in Israeli Genocide in Gaza

On the Conscience, a couple of days before we were intercepted, we held a memorial service for all the journalists and medical personnel who have been killed in Gaza. The artists onboard the ship had drawn a tree on a bulkhead facing the muster deck area. Above the tree were the words, “they tried to bury us, but they didn’t realize we were seeds.” The names of all the journalists and medics who have been killed in Gaza were written around the roots of the tree. For the memorial, we read the names of all these people. It took over an hour. After the names were read, a few medics who have worked in Gaza got up to speak about their experiences there.

One of the speakers was a doctor, a surgeon. I can’t remember which hospital he worked at in Gaza. He recounted the story of arriving in Gaza and finding his Palestinian colleagues at the hospital living in rubble. Even though they were living in rubble, they still were going out of their way to honor his presence in Gaza, walking miles to buy ingredients to make special meals for him. Spending money he didn’t think they had for these same meals. He became quite close with his Palestinian colleagues.

It’s been a couple of weeks now, so my memory of what he said is fuzzy. But the gist of it is, that when his visa was up and it came time for our surgeon to leave, his Palestinian colleagues told him not to go. They didn’t want him to leave. But he had to go because those are the rules. And he was tormented by this. As I am, after hearing him say this at the memorial service.

This doctor was with us on the Conscience to go back to Gaza. He told us at the service that when he got back there this time, “I am never leaving again.”

It’s my job to help get the boats to Gaza. To help get this man back where he belongs.

They can threaten us. I’ll ignore those.

They can bomb our ship. We’ll have it repaired.

They can torture us. I’ll shake it off.

If they go further, there are new boats out there.

There are plenty of engineers.

God willing, I’m not going to stop sailing.

I know there are plenty of folks who feel the same way.

A poem from my dear brother, a Palestinian refugee in Europe

I Am from There, I Am from Here

I used to listen to Darwish say it,

without truly understanding what he meant

by “to be in the no-place.”

I thought it was only a poet’s philosophy.

But now, as a Palestinian refugee living far

from my homeland,

I finally understand:

to be, and not to be –

to live with your body in exile while your soul remains suspended there,

in the homeland that never leaves you for a

single moment.

I asked myself: Who are we?

Why do we resist?

Why did we become refugees?

And I found the answer – not in books or

speeches,

but in the first tent, in the faces of our mothers,

in the memory of our children:

Because we refused to be slaves to Zionism.

Because we carried our homeland with us

when the world turned its back.

Because we did not let it be stolen from our

hearts.

Because we held on to life, even when they

wanted us to die.

Because we are – Free Palestine.

Edward DiGilio is a a boat repair technician, boat-builder and marine mechanic, and peace activist who works in the areas of global health, nuclear weapons abolition and Palestinian human rights. He has been on the crew of the Gaza Freedom Flotilla Coalition ships Handala (in 2024) and the Madleen (in 2025) for short trips in the Mediterranean. He was the ship’s mechanic on the 2025 Conscience. He has been a member of the Ground Zero Center for Non-Violent Action in Poulsbo, WA, for the past 11 years. He He lives on the Chesapeake Bay in the state of Maryland.