Above Photo: Soohee Cho/The Intercept

MUCH OF THE U.S. political system was flummoxed two weeks ago when a brand new 29-year-old congressperson made a seemingly radical proposal on “60 Minutes.”

Here’s what Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., said that wound everyone up: The U.S. should tax income over $10 million per year at a top rate of 60 or 70 percent.

Republicans responded by shamelessly lying about what this meant, pretending that Ocasio-Cortez was advocating a tax rate of 70 percent on all income. Some older Democrats, such as House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer and former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, adopted the standard Democratic tactic of cowering in fear before a deceptive Republican onslaught, like abused dogs.

The hullabaloo was understandable: Ocasio-Cortez’s forthright advocacy demonstrated that American politics, against the odds, can sometimes be about what Americans want. After the “60 Minutes” episode aired, The Hill commissioned a poll that found that 59 percent of registered voters support raising the top marginal tax rate to 70 percent. The idea, The Hill wrote, even receives “a surprising amount of support among Republican voters. … 45 percent of GOP voters say they favor it.”

However, the only surprising thing about this Republican support was that The Hill found it surprising. For the past 40 years, polls have uniformly shown that there is essentially no constituency for cutting taxes on the wealthiest Americans or corporations — and a huge constituency for raising them.

Two prominent political scientists, Martin Gilens at the University of California, Los Angeles and Benjamin Page at Northwestern University, have carefully studied the U.S. political system and demonstrated with charts and tables what most of us believe intuitively: If you don’t have money, you don’t matter. Or as Gilens and Page put it, “Not only do ordinary citizens not have uniquely substantial power over policy decisions; they have little or no independent influence on policy at all. By contrast, economic elites are estimated to have a quite substantial, highly significant, independent impact on policy.”

The last 40 years of U.S. tax policy have been the most striking demonstration imaginable of this assertion. Americans have never, in living memory, been averse to higher taxes on the rich. Nonetheless, the top marginal tax rate for the federal income tax plunged during the Reagan administration, from 70 percent to 28 percent, and has since only inched back up to 37 percent.

Republicans, many Democrats, and well-paid television journalists have browbeaten Americans for years with tales of how raising taxes on the wealthy would obliterate the U.S. economy. But the historical fact is that the economy has thrived with top rates of 80 percent or higher. In fact, as tax rates have come down, so has the rate of economic growth.

The top marginal corporate tax rate likewise dropped precipitously under Reagan, from 46 percent to 34 percent. Thanks to Trump’s 2017 tax bill, it’s now down to 21 percent.

These changes were not driven by popular demand. A 1978 Roper Organization survey found that a rousing 7 percent of Americans believed that the federal income taxes were unfair to high-income families. According to that survey, 5 percent felt that the tax rate was unfair to large corporations. And when the survey was repeated in 1986, the numbers were almost exactly the same: 7 percent and 6 percent, respectively, were worried that the rich and corporations were overtaxed.But it did not matter; the top marginal rates continued to fall.

Chart: Gallup

Gallup began regularly polling on this question in the early 1990s. Support for raising taxes on the rich has generally fluctuated between 60 and 70 percent, with around 10 percent wanting to cut them.

An even higher percentage of Americans, usually in the high 60s, have wanted to raise taxes on corporations. Instead, the top corporate marginal rate stayed constant at 35 percent from 1995 onward. Finally in 2017, after years of expensive lobbying, Trump and the GOP did the exact opposite of what Americans wanted, and slashed the top corporate rate almost in half.

All in all, the polling numbers are strikingly constant: Big majorities of Americans have always wanted to make the rich pay more. It’s one of the most popular political positions imaginable, with only teeny-tiny minorities calling for tax cuts for the country’s millionaires.

EVEN MORE REMARKABLY, as Gilens determined in a recent book, even the well-to-do at the 90th percentile of household income – currently, that’s about $175,000 per year — strongly support higher taxes on the rich. Are there any Americans who don’t like the idea?

Yes.

It’s notoriously difficult to poll the super-wealthy. There aren’t many, by definition. They’re tough to find. And they’re generally not interested in divulging their political views to pollsters.

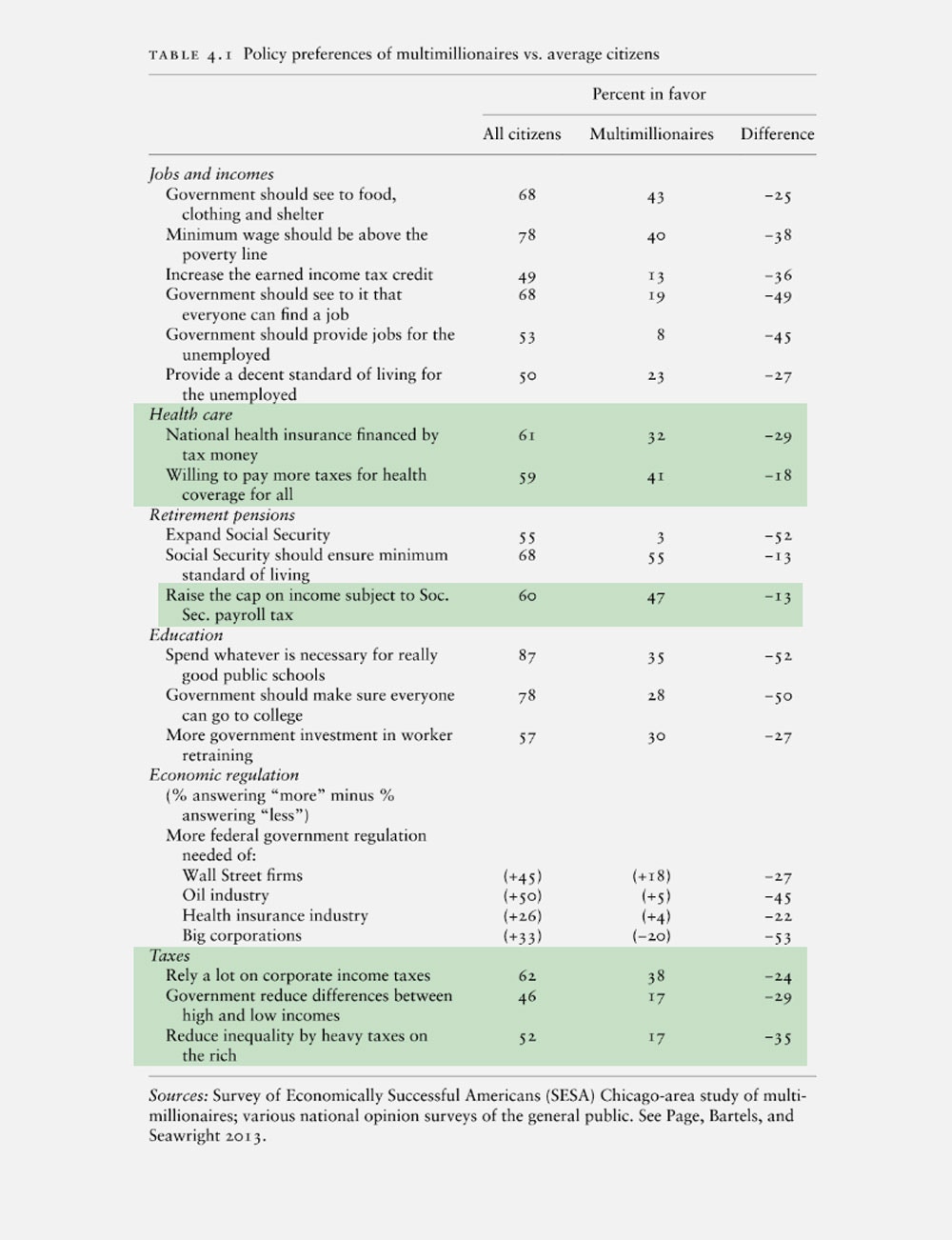

There have only been a handful of successful attempts in U.S. history. A recent one is the Survey of Economically Successful Americans, which questioned over 100 Chicagoans with a net worth of $10 million or higher. As Gilens and Page describe in another book, these multimillionaires are far more economically conservative than the general public, including on taxes. For instance, 52 percent of ordinary Americans told pollsters that the government should “reduce inequality by heavy taxes on the rich.” The Chicago study found that just 17 percent of the rich liked the sound of that.

This is what raw power looks like. The rich get what they want, or at least can stop policies they don’t want — even if everyone else in America badly desires them.By contrast, taxes can be raised, repeatedly and significantly — as long as they fall hardest on the poor. The tax on gas went up during the 1980s and early 1990s, from 4 cents a gallon in 1981 to 18 cents in 1993, or about 200 percent in constant dollars. Gilens points out that this was a rare tax policy strongly opposed by low-income Americans but viewed with equanimity by the more affluent.

Join Our Newsletter

Original reporting. Fearless journalism. Delivered to you.

So yes, people are still allowed to vote every two years or so. But money votes, too, far more voluminously, and via lobbying and campaign contributions, it votes every day. For decades, everyday Americans have had little influence on how their country is run.

But this hasn’t always been true in U.S. history, and no rule of nature says it has to stay this way forever. The ferocious pushback against Ocasio-Cortez demonstrates the fear at the top that one day many other politicians will decide it’s in their interest to side with the vast majority of Americans.