Above Photo: People gather to protest against the National Court’s decision to imprison civil society leaders without bail in Barcelona, Spain on Oct. 17, 2017.

JULIAN ASSANGE HAS been barred from communicating with the outside world for more than three weeks. On March 27, the government of Ecuador blocked Assange’s internet access and barred him from receiving visitors other than his lawyers. Assange has been in the Ecuadorian embassy in London since 2012, when Ecuador granted him asylum due to fears that his extradition to Sweden as part of a sexual assault investigation would result in his being sent to the U.S. for prosecution for his work with WikiLeaks. In January of this year, Assange formally became a citizen of Ecuador.

As a result of Ecuador’s recent actions, Assange — long a prolific commentator on political debates around the world — has been silenced for more than three weeks, by a country that originally granted him political asylum and of which he is now a citizen. While Ecuador was willing to defy Western dictates to hand over Assange under the presidency of Rafael Correa — who was fiercely protective of Ecuadorian sovereignty even if it meant disobeying Western powers — his successor, Lenín Moreno, has proven himself far more subservient, and that mentality — along with Moreno’s increasingly bitter feud with Correa — are major factors in the Ecuadorian government’s newly hostile treatment of Assange.

Yet many of the recent media claims about Assange that have caused this standoff — which have centered on the alleged role of Russia in the internal Spanish conflict over Catalan independence — range from highly dubious to demonstrably false. The campaign to depict Catalan unrest as a plot fueled by the Kremlin, Assange and even Edward Snowden have largely come from fraudulent assertions in the Spanish daily El País and highly dubious data claims from the so-called Hamilton 68 dashboard. The consequences of these false and misleading claims — this actual “fake news” — have been multifaceted and severe, not just for Assange, but for diplomatic relations among multiple countries.

The Guardian reported last week that doctors who recently visited Assange concluded his health condition has become “dangerous.” The journalist Stefania Maurizi of La Repubblica yesterday confirmed that Assange “is still in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London and unable to access the internet and to receive visitors,” while the official WikiLeaks account provided further details about the restrictions Assange faces:

Ordinarily, Western commentators would be lining up to denounce a country like Ecuador for blocking the communications and internet access of one of its own citizens. But because the person silenced here is Assange, whom they hate, their heartfelt devotion to the sacred principles of free speech and a free press vanish.

(When Ecuador first granted asylum to Assange, both the Ecuadorian government and Assange’s lawyers have always said that Assange would board the next flight to Stockholm if the Swedish government gave assurances it would not extradite him to the U.S. Although Swedish prosecutors last year dropped the sex assault investigation into Assange, Trump CIA Director Mike Pompeo has vowed to do everything possible to destroy WikiLeaks and prevent it from publishing further, while the U.K. government — an ally of the Trump administration — has vowed to arrest Assange on bail charges if he leaves the embassy.)

Evidence has now emerged that the cutting off of Assange’s communications with the outside world is the byproduct of serious diplomatic pressure being applied to the new Ecuadorian president, pressure that may very well lead, perhaps imminently, to Assange being expelled from the embassy altogether. The pressure is coming from the Spanish government in Madrid and its NATO allies, furious that Assange has expressed opposition to some of the repressive measures used to try to crush activists in support of Catalan independence.

The day after blocking Assange’s communications with the outside world, Ecuador issued a statement alleging that Assange’s public statements are “putting at risk” Ecuador’s relations with other states. The Ecuadorian government has previously expressed dissatisfaction with some of Assange’s political activities and statements, but the breaking point appears to have been a series of tweets from Assange about the arrest in Germany earlier this month of former President of Catalonia Carles Puigdemont.

Beginning in September, Assange had been tweeting regularly about the referendum for independence in Catalonia. Back then, Ecuador released a statement criticizing these tweets and emphasizing that “Ecuadorian authorities have reiterated to Mr. Assange his obligation not to make statements or activities that could affect Ecuador’s international relations.”

But why did these tweets about Catalonia, of all of Assange’s tweets about politics in other countries and the role he played in the 2016 U.S. election, lead — after five years — to such a response? And why now? And why and how did the West succeed in convincing so many of its citizens that the movement for Catalan independence — which has been a source of internal conflict in Spain for years — was now suddenly fueled by a Kremlin plot with Putin as the puppet master?

The answers provide a vivid example of how claims about “fake news,” Western propaganda, and disinformation can be used as a tactic for political manipulation. The circumstances leading to recent events extend beyond Julian Assange and understanding them requires background on political pressures in Spain, Ecuador, the United States, and the United Kingdom, and how these intersect with Assange’s case.

THE TENSIONS BETWEEN Ecuador and Assange center on the debate in Spain over Catalan independence. On October 1, 2017, the autonomous region of Catalonia held a referendum for independence. The Spanish government declared this referendum illegal. Protests and arrests of Catalan activists ensued, as well as the seizure of ballots and raids on polling stations by the government in Madrid.

In the midst of this crisis, former Spanish Prime Minister Felipe González reportedly requested that Spain’s most powerful media conglomerate, Grupo PRISA, which owns El País, “offer a firm response” to the independence movement in Catalonia. The media corporation complied, devoting its full resources to opposing Catalan secession.

El País, days later, began depicting Catalan activists as a tool of the Kremlin. The paper published an article alleging that not only Assange, but also Edward Snowden, were helping Russian propaganda networks spread “fake news” about Catalonia. El País repeated these claims in subsequent stories, which were echoed in reports from other anti-separatist organizations, such as the Spanish think tank Elcano Royal Institute, Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab, and NATO’s StratCom.

El País, Sept. 25, 2017

Once El País endorsed these fantastical allegations — that Assange and Snowden were helping to lead a Kremlin campaign to promote Catalan separatism — they were cited by or brought before legislative bodies around the world, in Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. But while these accusations are being taken seriously, they — like many claims about “fake news” and foreign online propaganda campaigns — are not being critically scrutinized or journalistically verified, and have little evidentiary support.

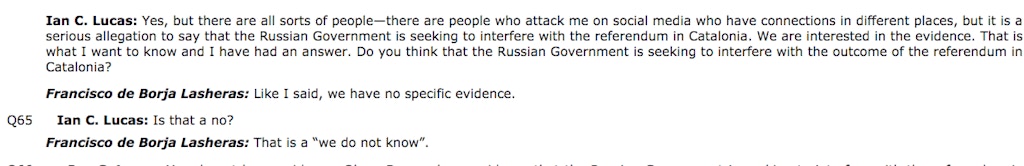

When pressed, many of those advancing these claims admit they have no definitive evidence of Russian government interference during the referendum in Catalonia, capable of citing only what they regard as biased reporting from RT and Sputnik. This exchange, from a House of Commons hearing on “fake news,” illustrates this point:

Yet — as they do with most Western problems these days — they continue to depict the conflict in terms of Russian propaganda because, they themselves acknowledge, they cannot comprehend the tensions in Spain except as a Kremlin operation. As Mira Milosevich-Juaristi from Elcano said when testifying before the Comisión Mixta de Seguridad Nacional in Spain: “The complexity and combination and coordination, which all occur at the same time, need an actor either governmental or near the government to coordinate it.”

Accusations that online support for Catalan independence was a Russian plot led by Assange and Snowden became a widespread belief. From the start, it was based overwhelmingly on a crude “dashboard” calling itself “Hamilton 68″ that is maintained by the Alliance for Securing Democracy. The “dashboard” purports to track “the activities of 600 Twitter accounts linked to Russian influence efforts online.”

That Catalonia was trending among the supposedly pro-Kremlin accounts monitored by the dashboard was offered by El País as what the paper called “definitive proof” — definitive proof — “that those who mobilize the army of pro-Russian bots have chosen to focus on the Catalan independence movement.”

But from its inception, the dubiousness of Hamilton 68 was self-evident. As The Intercept reported when the group was first formed, it was a brand-new foreign policy advocacy organization created by the exact people with the worst records of lying and militarism in Washington: Bill Kristol, former CIA officials, GOP hawks, and Democratic Party neocons.

Even worse, Hamilton 68 was, and remains, incredibly opaque about its methodology, refusing even to identify which accounts they designate as “promoting Russian influence online.” These marked accounts not only include “accounts that clearly state they are pro-Russian or affiliated with the Russian government,” but also “accounts run by people around the world who amplify pro-Russian themes either knowingly or unknowingly” (which often includes any dissent from the U.S. foreign policy orthodoxies endorsed by the neocons and CIA officials who created the group, now branded as “pro-Russian”).

Despite all of these glaring reasons for skepticism, U.S. media outlets repeatedly ingested the claims of this brand-new, sketchy group about what “Russian bots” are saying without an iota of critical thought or questioning, constructing one headline after the next based exclusively on the claims of this murky, shady group. As Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi recently documented, “More and more often now, the site’s pronouncements turn into front-page headlines.”

But in recent months, the credibility of Hamilton 68 has been widely challenged. Journalists and researchers have identified numerous inaccurate stories that were based on Hamilton 68 data, examined the involvement of highly ideological actors in the development of the tool, and questioned the “secret methodology” of Hamilton 68 and specifically its bizarre refusal to disclose the list of 600 accounts on which it bases its data. Some additionally note that the narrative about Russian bots and trolls is increasingly used as a tool to discredit a wide variety of legitimate political movements around the world.

Often, these media stories based on Hamilton 68, that fuel hysteria over Russian control of the west, are founded upon a poor understanding of what can and cannot be affirmed based on the data. The U.S. media’s abuse of this data finally caused even one of the creators of Hamilton 68 to express frustration with these inaccurate conclusions based on the most superficial understanding of the data, saying: “It’s somewhat frustrating because sometimes we have people make claims about it or whatever — we’re like, that’s not what it says, go back and look at it.”

MISUNDERSTANDING SOCIAL MEDIA analytic tools is a common problem in fake news reporting and can lead to erroneous conclusions with real political consequences. One illustrative example is the claim by El País – in its seminal article depicting Catalan independence as fueled by the Kremlin — that “a detailed analysis of 5,000 of Assange’s followers on Twitter provided by TwitterAudit, reveals that 59% are false profiles.”

El País’s claim is a demonstrable, obvious fraud. This assertion was entirely inaccurate because the data was from an inactive account with no tweets. Assange created a personal account years ago, but only started using it to tweet for the first time on February 14, 2017. But the Twitter Audit data used by El País to make this extraordinary claim — that Assange’s following is mostly composed of bots — is from February 2014, three years before anything was tweeted from the account.

To put it mildly, the archaic data used by El Pais regarding Assange’s account is wildly inaccurate for claims about his current followers. After reassessing @JulianAssange’s followers on November 24, 2017, Twitter Audit now shows that 92% of his followers are real.

Twitter Audit still claims that 8% of Assange’s followers are bots or otherwise fake, but this is relatively low considering that recent scientific studies estimate that “between 9% and 15% of active Twitter accounts are bots.”

It is also low relative to the results for other accounts with many followers. For example, Twitter Audit estimates that 25% of the @el_pais followers, 17% of @BarackObama’s followers, 27% of @RealDonaldTrump’s followers, and 48% of @EmmanuelMacron’s followers (as of nine months ago) may be fake accounts. Social media tools like Twitter Audit generally only provide rough heuristics, which are meaningless in isolation.

Correctly interpreting the results of social media analytics tools requires not only closely examining the data and understanding the limitations of the tools, but also comparing to known benchmarks from scientific studies and controls.

One example of this dubious methodological approach is the claim from both El País and DFRLab that a particular tweet by Julian Assange spread suspiciously quickly. On September 15, Assange tweeted: “I ask everyone to support Catalonia’s right to self-determination. Spain cannot be permitted to normalize repressive acts to stop the vote.”

El País argued, in the excerpt provided above, that “in the case of the tweet from Assange, as with many of his messages on the social media platform, it received 2,000 retweets in an hour and obtained its maximum reach – 12,000 retweets, in less than a day. The fact that the tweet went viral so quickly is evidence of the intervention of bots, or false social media profiles, programmed simply to automatically echo certain messages.”

The claim that retweet rates should gradually accelerate over time may make intuitive sense, but neither El País nor DFRLab provided any citations to research on these dynamics. In fact, at least one study has found that these supposedly intuitive hypotheses about retweet rates are wrong, and instead “half of retweeting occurs within an hour, and 75% under a day.” In the case of this particular tweet from Assange, only one-sixth of the retweets occurred in the first hour.

The overall spread of the tweet is also normal relative to Assange’s other tweets. Each of Julian Assange’s tweets between August 1 and December 12, 2017 was seen by 232,249.63 people on average. The specific tweet that El País scrutinized received 761,410 impressions (that is, this particular tweet was shown to other Twitter users 761,410 times). This is a bit higher than normal, but not disproportionately so; Assange’s most popular tweets regularly receive 3 or 4 million impressions, 4 to 6 times as many as the tweet that El País said must have been amplified by bots.

Shoddy claims of this sort could be avoided if journalists reporting on “fake news” attempted to follow reliable empirical methods in even a basic way — or at least the commands of basic rationality — by verifying whether the behavior that is claimed to be unusual actually is out of the ordinary. It is especially important to use valid methodology when reporting on allegedly “fake news” because misleading the public due to mistakes or exaggerated claims can lead to escalation of political tensions; ironically, deceitful attempts to identify and warn of the menace of Fake News, such as those peddled here by El Pais, can easily transform into a dissemination of Fake News.

(A full report with more detailed data regarding these empirical claims was recently submitted by one of the authors of this article, McGrath, to the U.K. Committee on Fake News.)

RECITING CLAIMS that match a commonly stated narrative, such as Russian interference in various western problems, is no substitute for fact-based analysis. One of the more methodologically unsound tactics used is to depict not only RT and Sputnik, but anyone who is quoted or even retweeted by them, as assisting in the spread of Russian state propaganda. During his testimony for the U.K. fake news committee, David Alandete from El Pais stated that “RT and Sputnik are at the center of this. Assange and Snowden are a very handy source for them; anything that Assange says is a quote and a headline.”

Assange was mentioned multiple times in RT and Sputnik’s coverage about Catalonia, but the stories quoting Assange comprised only a small minority of their discussions of these political events. Analysis of Sputnik and RT’s stories based on both Media Cloud’s data and their tweets reveal that only 1% to 3% of RT and Sputnik’s stories about Catalonia also mention Assange. Additionally, most of these references to Assange are centered around a few isolated quotes and events, in contrast to RT and Sputnik’s continuous coverage of the situation in Catalonia more generally.

Rather ironically (given the claims about bots and trolls promoting messages about independence in Catalonia), there is clear evidence of Twitter bots spreading messages about the crisis in Spain — but those were non-Russian bots and they were spreading propaganda that was opposed to Catalan independence. This is hardly the first time that Western governments and its allies have been caught using fake online activity to spread Western propaganda, but few western commentators care except when Russia or other U.S. adversaries do it.

Whatever else is true, it is likely that bot manipulation has been used in inflame the crisis in Spain — but they have been used to spread anti-Catalan messaging in line with Madrid authorities. On September 11, 2017, the user with the name @marilena_madrid tweeted a link to a story that Spain’s ABC published several months previously, which emphasized Puigdemont’s lack of legitimacy with EU institutions: a key anti-independence theme from Madrid authorities:

This @marilena_madrid tweet was retweeted over 15,000 times, but “liked” only 99 times. Researchers working on Twitter bot detection have discovered that bots often have low likes-to-tweets ratios of exactly this type:

In contrast to Assange’s tweets, which receive 1.14 “likes” per retweet on average — reflecting that they are spread overwhelmingly by actual humans — this anti-Catalan tweet from @marilena_madrid has a “likes” per retweet ratio of only 0.0062. A large number of the retweeters have random gibberish usernames such as @M9ycMppdvp5AhJb, @hdLrUNkGitXyghQ, and @fQq96ayN3rikTw, which also indicates that they may be bots.

Most of the accounts that retweeted @marilena_madrid, as well as @marilena_madrid’s account itself, now appear to be suspended by Twitter. Unfortunately, it is not possible to view data about suspended accounts except from on pages previously archived or cached, so there is limited data to study this particular set of bots in more detail. Thus, it is not possible to assess if this was an individual who had their tweets promoted by bots, a social media strategy by ABC to spread their stories with bots and trolls, or a state-sponsored propaganda campaign. Nevertheless, this case exemplifies the need for more multisided analysis about who is really using bot campaigns to propagandize the public.

It is certainly likely that one could find some actual Russian bots posting messages supportive of Catalan independence, but the magnitude has been wildly exaggerated by El Pais and many other Western institutions to the point of fabrication.

IF, AS APPEARS TO BE TRUE, these unsupported allegations about spreading disinformation during the referendum in Catalonia are being used as a tool for political manipulation in the case of Julian Assange, it is working. The escalation of tensions with Spain, which has strong diplomatic ties to Ecuador, threatens Assange’s asylum in a way that the longstanding pressure from the United States and United Kingdom could not. The intersection of these issues has lead to a rapidly deteriorating diplomatic situation, founded in part on exaggerated and inaccurate claims of disinformation during the referendum in Catalonia, where Ecuador is being forced to choose between maintaining their relations with other states and upholding Assange’s asylum.

The pattern of events seen here is not specific to Julian Assange, Ecuador, Spain, or any one country. It is a global, systemic problem. This situation an illustrative example of what happens when political tensions around internal divisions, in this case Spain and Catalonia, build and break. In the aftermath, people struggle to explain what they see as an injustice, and conclude that some foreign person or group interfered to bring about a problematic situation by spreading propaganda or disinformation.

This narrative grows and shifts the focus away from internal problems and divisions by unifying people against this new external enemy, much the way patriotism surges during a war. This sentiment can then be exploited as a tactic of manipulation for those seeking to support their own agendas, and leveraged to pressure external parties. It is also an extremely powerful tool for stigmatizing any internal, domestic dissent aligned with, if not controlled by, the foreign villain. Meanwhile, internal tensions continue to build and conflicts escalate, with their actual causes ignored in favor of pleasing, simplistic, self-vindicating storylines about foreign interference.

Correction: April 20, 2018

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Spanish newspaper ABC was owned by Grupo PRISA. It is owned by Vocento.