Above Photo: Alana Semuels / The Atlantic

Labor unrest is spreading through the factories on the border, where people say they deserve more than $6 a day.

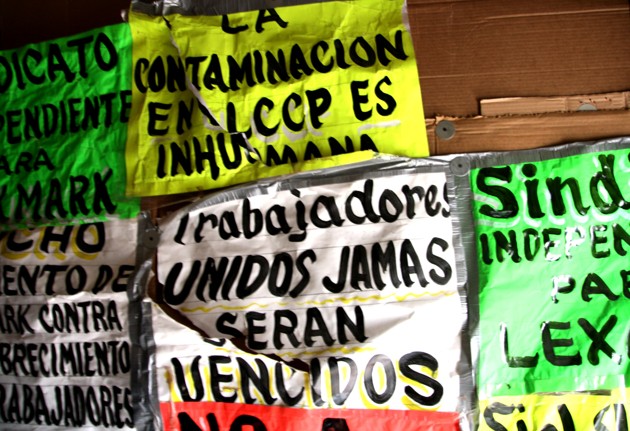

CIUDAD JUAREZ, Mexico — Women and men, more than 70 of them, were fired on December 9th from the factory on the Mexican side of the Mexico-Texas border where they made printers for the American company Lexmark. They say they were terminated because they were trying to form an independent union. The company says they were fired because they caused a “workplace disruption.”

Now, the workers protest by occupying a makeshift shack outside the factory, still advocating for a raise and for a union, even though they no longer have jobs. Outside, a spray-painted banner reads “Justicia A La Clase Obrera” meaning “Justice for the Working Class.” Inside, a wood stove burns as they make coffee and cook tortillas and wait for someone to hear what they have to say.

“We are hungry. Our children are hungry,” Blanca Estella Moya, one of the fired workers, tells me. “You cannot live on these wages in Juarez.”

“It’s not possible to live on these wages. It’s not human,” said Terrazas, who has dark, curly, dyed-red hair, and was wearing a plaid checkered blouse and jeans. “They are creating generations of slaves.”

It’s not just Lexmark: Workers at Mexican subsidiaries of FoxConn, Eaton, and CommScope in Juarez have all protested working conditions and compensation in recent months. Women tell of sexual harassment at the factories and of working multiple shifts to make ends meet. The devaluation of the peso has meant their money buys less than it once did. The protests come at an inopportune moment for Mexico. Many companies, especially automakers, aremoving production to Mexico after deciding that the costs and logistical headaches of manufacturing in Asia are too great to bear. Mexico is trying to welcome them with open arms.

But workers, especially those on the border, aren’t making that easy.

“This is a historic thing that’s happening here. In 50 years, there hasn’t been this level of labor discontent,” says Oscar Martinez, a professor at the University of Arizona who spends time in Juarez and has written numerous books on the border, including Border People: Life and Society in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. “We could be seeing the beginning of a larger movement that spreads to other parts of Mexico and challenges the whole system that has been created for these multinationals.”

The protests come at an inopportune moment for the U.S. as well. When Congress gets around to debating the Trans Pacific Partnership, it will surely look at NAFTA and the promises that treaty made for American and Mexican workers. The situation of the workers in Juarez makes it clear that NAFTA didn’t improve conditions as promised, and implies that TPP won’t work, either, said Cathy Feingold, the director of the International Department at the AFL-CIO. In addition, with little hope for U.S. immigration reform, the U.S. will have to recognize that it creates its own migration problems by allowing companies to treat workers so poorly just across the border, she said. When workers can’t make a decent wage in their own country, they’ll try to cross the border, she said.

“You can’t have an economy that’s this out of whack. It’s just not good for business,” she said. “If you have a global economy that’s this unequal, you have insecurity, and you have people moving for better opportunities.”

Other factors may continue to draw attention to the issue in upcoming months. The pope is visiting Juarez on February 17th, and many hope he will speak there about economic inequality, and perhaps specifically about the factory workers. There are elections in Juarez and the state it sits in, Chihuahua, later this year, putting additional pressure on politicians to address the concerns of the 250,000 factory workers of Juarez.

“It’s this perfect moment for really highlighting the intersection of failed trade policies, increased poverty, and then migration on the border,” Feingold said.

* * *

The maquiladoras, or border factories, have been around for more than 50 years. In 1965, after the U.S. ended the Bracero program, which had allowed Mexican laborers to work seasonally in the U.S., the Mexican government created the Border Industrialization Program. It essentially allowed foreign-owned (typically this meant American) companies to set up factories on the Mexican side of the border, import tariff-free raw goods for manufacturing and then export the finished products, employing low-cost Mexican workers along the way. The number of factories in border areas such as Juarez and Tijuana boomed in the 1980s, as U.S. companies facing wage competition from China saw Mexico as an easy option. There are now about 330 maquiladoras in Juarez alone, according to the Borderplex Alliance.

When NAFTA was ratified 1995, it opened the potential for companies to open factories anywhere in Mexico and still avoid tariffs, said Tony Payan, the director of the Mexico Center at Rice University. Regions across Mexico built up their roads, their airports, and their railways, and foreign companies began to realize that they could locate their factories throughout much of Mexico just as easily as they could on the border.

That’s led to downward pressure on wages. Indeed, while workers in countries such as China, Brazil, and Russia have seen wage increases in recent years, Mexican workers have seen almost no change. In 2011, hourly wages in China surpassed those in Mexico; now they’re 40 percent higher, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

The Juarez workers have suffered the most as factories there competed with others throughout Mexico for business. The average monthly wage for production workers in Juarez was $422 a month in December of 2014, compared to $582 a month for all Mexican workers, according to a report from the Hunt Institute for Economic Competitiveness at the University of Texas at El Paso. But, while the wage for Juarez production workers was the lowest out of all the regions surveyed, the wage for managers was the highest, at $2,238 a month, compared to $2,045 for all Mexico, the Hunt Institute found.

Average Monthly Wages at Export-Oriented Manufacturing Firms in Juarez by Region, in U.S. Dollars

The wage disparity is likely because many managers in the Juarez maquiladoras live in El Paso, and thus require higher salaries, and also because factories needed to pay a premium to attract managers during a violent period between 2008 and 2011, when tens of thousands of people in the region were killed, said Patrick Schaefer, the director of the Hunt Institute. In addition, the Juarez/El Paso region, called Paseo del Norte, is traditionally a magnet for migrants from Mexico and Central America who are heading north for a better life, creating a pool of low-skilled workers who compete for manufacturing jobs.

“These are products produced by people who are a couple steps above wage slavery,” said Kathy Staudt, a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso who has worked with a binational workers group, the Social Justice Education Forum, which is advocating for the striking workers. “It should bother people who have a conscience, but I think too many people don’t care.”

The Lexmark workers decided to try and form a union because they wanted better working conditions. Blanca Estella Moya, for example, was responsible for putting metal parts in a plastic cartridge, a job that made her wrists sore and caused tendonitis, according to Terrazas. The machine she worked with constantly broke, she says, and supervisors were unsympathetic, expecting her to continue to produce 1,700 parts a day, even with a broken machine. The workers called one manager “The Dog” because of his record of sexual harassment, according to Terrazas.

When coworkers asked Moya if she wanted to join a group advocating for better working conditions, she said she was interested. Her husband works in construction, and together they make about 28,000 pesos a month—about $1,500 dollars. Families in Juarez need about 58,000 a month in order to buy the basics to survive, Terrazas, the lawyer, says. Moya has five children, three of whom live with her, and she also provides for her grandson. Her family often needs to get loans just to pay the rent, and, like many other families working at the maquiladoras, they steal electricity and water because they can’t afford to pay for it.

At first, the company said orally that they would give workers the 35-cent raise they’d been asking for, Moya said. Then, they reneged on that, Terrazas, the lawyer said. When the workers came to her asking what they could do, she explained there was very little recourse. All they could do, she said, was join an independent union and try to advocate for better pay.

When I asked Lexmark about this version of events and other questions about wages and working conditions in Juarez, they insisted on getting written questions rather than talking on the phone. They then declined to answer most of the questions I sent.

“We meet or exceed the standards of all laws for manufacturing facilities in Juarez, Mexico,” Jerry Grasso, the vice president of corporate communications at Lexmark International wrote, in response to one question, the only of six that he agreed to answer. (He later followed up to answer another question about why the workers were fired by specifying that they were “let go for workplace disruption in our Juarez plant.”)

A 35-cent raise may seem like a pittance for a company with billions in revenue, but Lexmark may feel squeezed by falling profits. In October, the company reported lower-than-expected third-quarter earnings, which have fallen from $350 million in 2010 to $79 million in 2014, according to Lexmark’s annual report.

A representative for Foxconn gave a more detailed response, writing that Foxconn’s Mexican subsidiary pays wages that are “in excess of statutory requirements” and benefits that are competitive with peer businesses. It holds salary reviews and performance reviews frequently, according to a statement sent to me from a PR firm representing Foxconn Technology Group.

“It is unfortunate that a small number of the company’s employees have chosen to try to disrupt its operations to promote their personal agendas outside of the law and the approved and recognized company channels of communication,” the statement said.

* * *

Technically, there are unions in Mexico. But they’re not unions in the American sense of the word, according to Feingold, the AFL-CIO International director. Most so-called unions are what the AFL-CIO calls protection contracts, which are essentially collective-bargaining contracts signed between an employer and an employer-backed union, often without the knowledge of the workers. Only about 1 percent of the workforce in Mexico is organized in independent unions that give more of a voice than protection contracts, she said.

Protection contracts are hard to change because they are created between private companies and unions that purport to represent workers, Feingold said. Mexican labor laws protect the unions that sign the protection contracts, said Staudt, the UTEP professor, even if they don’t protect the workers.

At a meeting of labor ministers of the Americas in Cancun last month, Mexican representatives said they were interested in making sure that workers had better working conditions. But the government has not seemed interested in helping effect change for the Juarez workers, Terrazas said. On December 30, representing the workers, she went to the local labor authority, the Conciliation and Arbitration Board, and filled out the paperwork to form an independent union. The request was denied, she said, because the labor board said the workers did not establish the conditions needed for a union, such as an official union building and fundraising committee. The workers presented their position for a second time on January 2 and are now waiting for a second decision.

“We hope this will be a precedent for the people living in this country, that we will be a leader for wages,” another worker, Maria Margarita Morta Dias, said.

Experts on the border region and on labor told me that they had little hope that the workers’ movement would succeed. Workers have had so few rights in Mexico for so long that there’s little reason for anything to change, they said. Especially now that factories in Juarez are facing more, rather than less, competition. After all, little changed in Mexico after a Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times investigation unveiled widespread bribery at Walmart there, nor after international groups tried to draw attention to the hundreds of murders of women who had been working in the maquiladoras of Juarez. State and federal police are likely going to start harassing the protesters soon, these observers say, driving them underground.

Terrazas herself says there are signs that the government and the factories are colluding to punish agitators. The names of the workers who asked to form a union were supposed to be secret, she said, but after they submitted the petition, 90 workers were fired, 75 of whom had signed the petition. Lexmark employs between 2,700 and 3,000 workers at its Juarez plant, Terrazas said, a number the company would not confirm.

Still Terrazas and other advocates say there are a few things that are different this time. Some 700 workers in Juarez joined a “slowdown” at the factory, which Terrazas said prompted the firings and signaled widespread sympathy for the protesters. Workers in El Paso and Lexington, Kentucky, the home of Lexmark, have been staging rallies in solidarity with the Mexican maquiladora workers. The group has received donations and help from as far away as Geneva, and dozens of people across the border in El Paso have been listening and donating, she told me. The donations from abroad have made it possible for the workers to continue to stay outside the factory, despite the freezing temperatures and freezing rain. And other factories in Juarez have given workers small raises in the time the Lexmark workers have been protesting, she says. Even a supervisor who harassed workers has been fired since the workers started protesting, Terrazas said.

These workers seem uniquely determined to change something in their lives, she said. I met with four women in the shack outside the factory; when I asked how many of them had parents who worked in the maquiladoras, all four raised their hands. One woman had dropped out of school after second grade when her mother told her the family didn’t have enough money to pay for books and fees.

With Terrazas’s help, though, the workers seem aware that this kind of generational poverty does not have to continue. One of the earliest deciding battles of the Mexican Revolution began in Ciudad Juarez, Terrazas said. This could be the beginning of another radical campaign of change.

If globalization has made it possible for factories to locate across borders, after all, it has also made it possible for workers to unite across borders. The workers in Mexico join those in the U.S. in contesting the status quo, in which those at the bottom have so much less than those at the top.

“The main cause of all the revolutions in the world, historically, is when the people are hungry,” Terrazas said. “And the people are hungry now.”