Above: Demonstrators set up a barricade to block an avenue at a bus station during a protest in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Friday, April 28, 2017. Public transport largely came to a halt across much of Brazil on Friday and protesters blocked roads and scuffled with police as part of a general strike to protest proposed changes to labor laws and the pension system. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

Just over one year ago, Brazil’s elected President, Dilma Rousseff, was impeached – ostensibly due to budgetary lawbreaking – and replaced with her centrist Vice President, Michel Temer. Since then, virtually every aspect of the nation’s political and economic crisis – especially corruption – has worsened.

Temer’s approval ratings have collapsed to single digits. His closest political allies – the same officials who engineered Dilma’s impeachment and installed him in the presidency – recently became the official targets of a sprawling criminal investigation. The President himself has been implicated by new revelations, saved only by the legal immunity he enjoys. It’s almost impossible to imagine a presidency imploding more completely and rapidly than the unelected one imposed by elites on the Brazilian population in the wake of Dilma’s impeachment.

The disgust validly generated by all of these failures finally exploded this week. A nationwide strike, and tumultuous protests in numerous cities, today has paralyzed much of the country, shutting roads, airports and schools. It is the largest strike to hit Brazil in at least two decades. The protests were largely peaceful, but some random violence emerged.

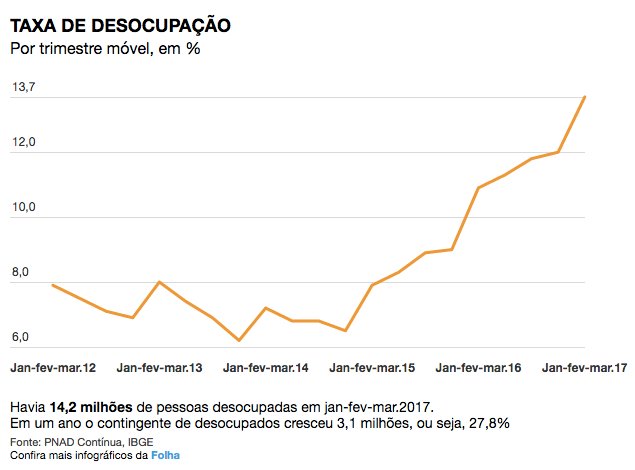

The proximate cause of the anger is a set of “reforms” that the Temer government is ushering in that will limit the rights of workers, raise their retirement age by several years, and cut various pension and social security benefits. These austerity measures are being imposed at a time of great suffering, with the unemployment rate rising dramatically and social improvements of the last decade, which raised millions of people out of poverty, unravelling. As the New York Times put it today: “The strike revealed deep fissures in Brazilian society over Mr. Temer’s government and its policies.”

But the actual cause is broader, and it is one familiar far beyond Brazil. During the past three years, Brazilians have been subjected to one revelation after the next of extreme corruption pervading the country’s political and economic class.

Scores of corporate executives and long-time party leaders are imprisoned. They include the head of the Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht, the House Speaker who presided over Dilma’s impeachment, and the former governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro. The current House Speaker, and Senate President, and nine of Temer’s ministers are now targets of criminal investigations for bribery and money laundering, as are numerous governors.

In sum, the vast bulk of the top-shelf political and economic elite have proven to be radically corrupt. Billions upon billions of dollars have been stolen from the Brazilian public. Recently released recordings from the judicial confessions of Marcelo Odebrecht, scion of one of Brazil’s richest families, depict a country ruled almost entirely through bribes and criminality, regardless of the ideology or party of political leaders.

And yet, even in the wake of this oozing and incomparable elite corruption, the price that is being paid falls overwhelmingly on the victims – ordinary Brazilians – while the culprits prosper. The same Brazilian politicians implicated in this criminal enterprise continue to reign in Brasília, as they enjoy virtual immunity from the law. Worse, they continue to exempt themselves from the austerity they impose on everyone else.

Imagine being a Brazilian laborer, working in poverty, spending years listening to stories about how corporate executives bribed political officials with millions of dollars in order to corruptly win state contracts – bribes that these elected officials used for yachts and luxury cars and European shopping sprees – only to then be told that there is no money for your retirement or pension and that you must work years longer, with fewer benefits, to save the country. That’s the tale which Brazilian citizens are being fed. The only mystifying aspect is that these types of protests have taken this long to erupt.

BUT THIS moral perversion – in which ordinary victims uniquely bear the burden for elite crimes – is familiar to citizens far away from Brazil. Indeed, one of the prime authors of Brazil’s economic suffering – the 2008 economic crisis caused by Wall Street – pioneered this odious formula.

The reckless tycoons and sociopathic financial wizards responsible for that 2008 economic collapse paid virtually no price for the harm they caused. To this day, none of them has been prosecuted for the financial chicanery that spawned it. Worse, the U.S. Government quickly acted to protect the interests of the culprits – bailing them out with public funds, protecting them from nationalization or break-up, preserving their ability to plunder with little risk to themselves.

At the same time, the victims of this recklessness – ordinary Americans – were forced to bear the full brunt of the fallout. Millions faced foreclosure, unemployment, and general economic suffering with little to no help from the U.S. government, which was busy protecting those responsible. Above all else, it was this inequity that spawned protest movements from Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party, and arguably laid the groundwork of resentment and a collapse of trust that gave rise to the Trump presidency.

This week’s controversy over Barack Obama’s $400,000 payday from a Wall Street firm for a single speech resonated not because it suggested he had acted illegally or even unethically. Rather, it symbolized, in a particularly glaring manner, the oligarchical character of U.S. political culture: the same president who repeatedly acted to protect the financial industry after it wrecked the global economy, and who shielded its leaders from criminal prosecution, was being lavished with the rewards.

Across Europe, the same dynamic prevails. Angry voters in the U.K. ratified Brexit, while once-liberal populations in western Europe are alarmingly open to über-nationalist and xenophobic parties. Much of this, too, is driven by the often-valid belief that elite institutions are completely indifferent to their deprivation and suffering, and repeatedly act only to advance the interests of a small group of economically and politically powerful actors at the expense of everyone else. Of course that belief is going to trigger instability, and resentment, and collective rage.

The austerity and deprivation now being imposed on ordinary Brazilians is not ancillary or unanticipated. To the contrary, it was the primary objective, the central aim, of the impeachment last year of the country’s president.

The left-wing party that ruled Brazil since 2002 (the Workers’ Party: PT) became increasingly neoliberal and accommodating to the country’s oligarchical class, often at the expense of its own base of union members and the working poor. Even the party’s two leaders – Lula and Dilma – began advocating the necessity of austerity measures. That, at least in part, explains why the party’s own base began abandoning it, leading to a drop in Dilma’s support sufficient to permit impeachment.

But Dilma was willing to go only so far with austerity – not as far as Brazilian elites wanted. In a moment of rare and uncharacteristic candor, her replacement, Michel Temer, admitted to a group of hedge fund mangers and foreign policy elites in New York last September that Dilma’s refusal to accept more severe austerity was one of the real reasons for her impeachment (the other real reason was revealed in a tape recording of Temer’s closest political ally, Senator Romero Jucá: to stop the ongoing corruption investigation before it consumed impeachment advocates).

In other words, Brazilian elites – having plundered the country to the point where it was close to collapse – decided that the only viable solution was to force the country’s already-suffering population of workers and the unemployed poor to suffer further, by taking from them the meager protections and safety net they enjoyed. They engineered the cataclysmic impeachment of the country’s president to achieve this.

Dilma’s replacement – the classic, pliable mediocrity that he is – was given one overarching task: to impose harsh austerity even if it meant becoming the target of widespread public hatred. The 75-year-old career politician – literally banned from running for office for 8 years due to his violation of election laws – had no intention or prospect to run again, so he happily agreed to perform his assigned duties in exchange for being given the mantle of power that he could never have earned on his own.

So that’s the tawdry spectacle of elite corruption, elite impunity and mass suffering driving today’s nationwide protest. Just as it did in the U.S. and Europe, this flagrant inequity is threatening to fuel a far-right, revanchist-nationalist movement in Brazil: one that actually makes its American and European counterparts pale in comparison when it comes to menacing extremism. The collapse of trust in the entire political class has created a genuinely frightening opening in the 2018 presidential contest for the far-right evangelical Congressman Jair Bolsonaro, who longs for the restoration of a military dictatorship, praises torturers as patriotic heroes, and routinely channels fascist rhetoric on a wide range of issues.

What’s most baffling about all of this is that no matter how many times global elites see the rotted fruit of their piggish behavior – instability, extremism and collective rejection of their own authority – they continue to pursue it, seemingly inured to the consequences. Brazil is just the latest example, but it should be a familiar one to people across the planet.